In order to capture audio for any medium, we use some type of transducer, which is any kind of device that transforms one kind of energy into another. For audio, both Microphones and Speakers are transducers that turn acoustic energy (sound pressure) into electrical signals, or turning electrical signals into acoustic energy.

There are two major categories of microphones: Dynamic and Condenser.

- Dynamic Microphones

-

By far the most common type of microphone, especially for live performances. They are typically low cost, able to handle very loud sounds, and stand up to lots of abuse.

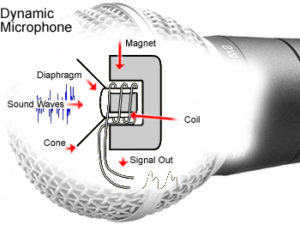

By far the most common type of microphone, especially for live performances. They are typically low cost, able to handle very loud sounds, and stand up to lots of abuse.- A physical cone leads incoming soundwaves to a faceplate, called a Diaphragm. The Diaphragm is connected to a magnet, both of which move back and forth in response to the compression and rarefaction inside of an electrical coil, acting like a generator. Then the resulting Alternating Current is sent to the device.

- In this way, acoustic energy is transformed into an electrical signal.

- Condenser (capacitor) Microphones

-

Typically found in professional recording studios, condenser microphones tend to be more frequency accurate than dynamic microphones and almost always sound amazing, but are more fragile, expensive, and require external power.

Typically found in professional recording studios, condenser microphones tend to be more frequency accurate than dynamic microphones and almost always sound amazing, but are more fragile, expensive, and require external power.- Instead of vibrating a magnetic coil, they have a capacitor made up of a thin diaphragm and a solid back plate. As the diaphragm vibrates, the distance between it and the back plate varies accordingly, creating fluctuating capacitance. This fluctuation creates an electrical output not unlike a dynamic microphone.

- To prime this capacitance, the microphone requires external power. Most audio interfaces can provide this.

- Ribbon Microphones

-

- Ribbon mics are essentially dynamic microphones with a different diaphragm in the shape of a ribbon.

- They were the first microphones developed back in the early days of radio.

- They tend to be extremely fragile, and fell out of style not long after the 1950’s.

- Have been coming back recently with improved durability and sound quality.

- DONT put phantom power through a ribbon microphone.

Don’t fear the Phantom

The electricity required to power a condenser microphones is extremely low. Even in the extremely unlikely case that a short in the system channels electricity into a human hand, the resulting shock would only be marginally worse than a static shock. Mishaps with electrictiy in audio environments is far more likely to occur with grounding issues in a high voltage system, which can be carried on any cable with or without phantom power.

Phantom power can harm ribbon microphones, but should not damage a moving-coil mic if phantom power is accidentally applied. Check that the mic requires phantom power for safety’s sake.

The danger in unplugging a phantom powered microphone (as with all other microphones) is the popping sound it can create in your speakers, which can be exceedingly loud. To protect your speakers, be certain to mute the channel or system before connecting or disconnecting a microphone. Additionally, be sure to turn phantom power off before unplugging. Doing so accidentally should not hurt the microphone, but it does not hurt to be safe.

Don’t send phantom power through an unbalanced cable (like a guitar cable) and especially do not plug in or remove any unbalanced cables that have phantom power running through them. This can create a short circuit that can damage your equipment.

Polar patterns

In addition to the type of transducer a microphone has, they also have varying polar patterns.

A Polar Pattern is the direction that microphones pick up sound. Think of it like a lens with varying width, capturing more or less sound.

There are 5 broad categories of polar patterns, which we will cover extremely briefly.

Electro Voice dynamic cardioid RE27 N/D microphone. About $500.

-

- Omnidirectional.

- Fairly common, picks up audio in all directions equally.

- Only polar pattern that is not subject to the proximity effect.

- Cardioid

- The most widely used type of mic, the cardioid has a directional polar pattern shaped like a heart.

- One benefit of the design is that it rejects sound from behind the diaphragm. That’s useful in live performances to avoid feedback from monitors.

- The proximity effect is the phenomenon where directional microphones increase bass response due to the proximity of the sound source. This is commonly associated with deep bass radio voices.

- The proximity effect is stronger as microphones get more directional.

- Super-cardioid

- More directional than cardioid microphones, rejects more sound from the sides and can detect audio from behind the diaphragm.

- Hyper-cardioid

- Much more directional than either supercardioid or cardioid mics.

- Boom microphones on movie or TV sets are typically hypercardioid mics or “shotgun” mics.

- They reject nearly all sound from the sides.

- Creates a “spotlight” of source audio.

- Bi-directional.

- Rejects sound from the sides and picks up audio in two directions simultaneously.

- Has extreme proximity effect.

Pre-amps

For any microphone recording, a preamp must be used on an audio signal as it is being reproduced. The reason is that the signal level from a microphone is incredibly small, and if reproduced without some kind of boost would be very weak when coming out of our speakers. The boost that a pre-amp gives a signal early in the signal chain is called Gain. It is important to set gain appropriately before recording, such that the signal is not too weak (increasing system noise later) or too loud (creating distortion by overloading the system.)

Instruments have a much louder signal output, but they too need gain. If your audio equipment has a Mic Level / Line Level setting, it is important to set the channel appropriately to either a Mic or Instrument level such that the system can capture either signal accurately.

- Omnidirectional.