Note: the following basic outline of media law is taken from a broader perspective available online here. (www.revolutionsincommunication.com/law)

———

1. Freedom of speech and press are fundamental foundations of civilization.

In the United States of America, the cornerstone of speech and press law is the First Amendment of the Constitution. It has six major clauses; two concerning religion, and one each in the areas of speech, press, assembly and petition:

In the United States of America, the cornerstone of speech and press law is the First Amendment of the Constitution. It has six major clauses; two concerning religion, and one each in the areas of speech, press, assembly and petition:

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.

Many other democracies are also committed to free speech and press, and have their own foundational human rights documents and guarantees.

The most significant international document is the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights. Article 19:

Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.

Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.

II. Why we need to appreciate media law

Everyone is a publisher. Everyone who uses the media needs to understand media law because new technologies make it possible for individuals to reach very large audiences. Totalitarian regimes (Saudi Arabia, China, others) and political extremists (such as the ‘alt-right’) claim that democracy does not work, and that dissent must be punished for the sake of order and social stability.

The democracies of the world utterly reject that idea. People in the US, Europe, Japan, South Korea, most of Latin America and Africa believe that respect for law and human rights helps to stabilize social systems. As a practical matter, it is easier to balance rights than to suppress them. More importantly, there is something deep in the human spirit that needs freedom. This is the basis of natural rights theory.

• Natural rights theory, developed during the Enlightenment era of the 1700s, takes the view that freedom is the natural human condition. Rights under this concept are not given (or endowed) by the state; instead they are given by nature or by God. A state or nation exists to protect rights; it does not, and cannot, “grant” rights. That’s why the US Declaration of Independence says:

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

This view developed in Western Europe during the Enlightenment period, but of course, Western Europe is not the only source of the idea of freedom of religion, speech or expression, or of democracy. In fact, the historic and global diversity of appreciation for human rights emphatically re-affirms the natural rights perspective.

• Free speech has a pragmatic function. and dissent can lead to constructive social change and improvements in the human condition. It serves as a “social safety valve.” Repression, on the other hand, alienates the people, making non-violent reform impossible and greatly increasing resentment and the likelihood of violence.

• Political opinions should never be censored, according to political philosopher John Stuart Mill in his book On Liberty, because it deprives the people: If the opinion is right, they are deprived of the opportunity of exchanging error for truth: if wrong, they lose, what is almost as great a benefit, the clearer perception and livelier impression of truth, produced by its collision with error.

Ben Eaton, Mary Schaeffer, Esther Calhoun, and Ellis Long (from left to right) successfully asked courts to dismiss a defamation lawsuit brought against them for speaking out about pollution in their Alabama town. The dismissal was expected, since everyone has a right to express their concerns about public issues even if they involve private companies. (Photo courtesy ACLU)

• Criticism of government and public officials is a civic duty. To speak out about public people and public issues, even to the point of sharp and vehement debate, is often seen as a citizen’s responsibility as well as a right. This idea was strongly endorsed in bedrock free speech case New York Times v Sullivan, but is a longstanding commitment in American discourse.

As US President Theodore Roosevelt once said: “To announce that there must be no criticism of the president or that we are to stand by the president right or wrong, is not only unpatriotic and servile, but it is morally treasonable to the American public.”

III. Libel and privacy

Libel is an untrue statement about a living person or existing institution that injures reputation by defamation, that is, by exposing them to public hatred, shame, disgrace or ridicule. (Slander is spoken defamation.)

Libel suits are civil (not criminal) in most of the world.

Public and private people: In the US and most other free countries, the law distinguishes between libel of public people and private people. A public person (like a football coach) can be criticized without much fear of a libel suit in the US unless the criticism is knowingly false or in reckless disregard for the truth. On the other hand, a falsehood about a private person can result in a libel suit if the defendant has simply been negligent.

Defenses against libel are: 1) Truth, 2) Fair comment & criticism, and 3) Privilege, that is, citing from “privileged” (official) documents such as court records.

Private people can successfully sue for “publication of private facts,” even if the facts are true, provided they are outrageous to an average person (such as showing a sex video, or disclosing a person’s health condition) and not ordinary (such as being a regular dog-walker).

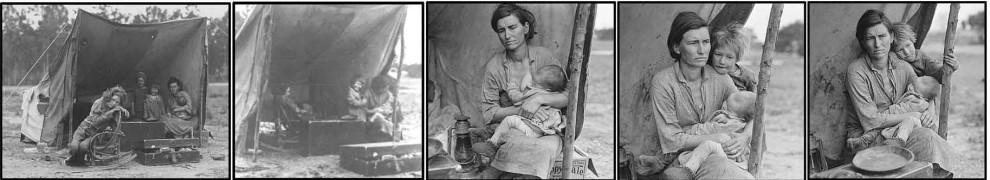

False light — Another type of privacy suit involves situations where a photo or a video clip is edited or captioned in a way that leads to a totally false conclusion. Although the photo or video clip may be truthful in the sense that it depicts one slice of reality, there are times when the context can be deceptive.

Mitigation: If you make a mistake, be ethical and admit it. A retraction and/or correction can mitigate (lower) court imposed fines.

Go beyond the overview. The above is just a quick overview to alert you to some of the possible issues. There’s more about libel and privacy, and about cases and hypotheticals, on this web site.