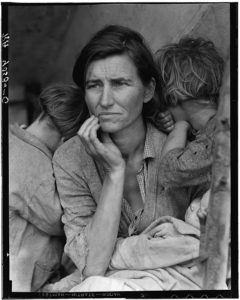

Images surround us in daily life. They inspire us, warn us, persuade us, and constantly compete for our attention. We don’t remember most of them, but some of them seem to stick with us. What is it that makes an image memorable or persuasive? How does a strong image appeal to our common psychological foundations? And, for example, why does this image by Dorothea Lange stand out from the others she took the same day in 1937? (The others are in the header, above).

It seems simple to begin with, but there are complex processes going on beneath the surface.

Visual communication is the original form of mass communication, going back long before the introduction of writing. Symbols formed the basis of written language.

These symbols and archetypes can be traced even further back, as a basis of human psychology, bound up in pre-historic memories. As we begin to ask questions about the power and social impact of visual imagery, we open a need to understand more about its physiological, psychological, historical, technical, aesthetic and ethical roots.

When we look at the work of great artists, designers, photographers, or filmmakers, we find that their work portrays some human emotion or a view of the human condition in a way that reaches into our own emotional systems and resonates at some depth. The question is how that takes place, and there is no one particular right answer, because visual communication is essentially about art and emotions, not science and logic.

The study of visual communication usually begins with the basic physiological and psychological foundation of vision and perceptio n. Another area of study incorporates aesthetic theories to help evaluate visual communication. A course in visual communication can also introduce practical skills and a set of methods for thinking about visual communication issues.

n. Another area of study incorporates aesthetic theories to help evaluate visual communication. A course in visual communication can also introduce practical skills and a set of methods for thinking about visual communication issues.