Early Dageurotypes by African American photographers James P. Ball, Glenalvin Goodridge, and Augustus Washington are part of a new display at the Smithsonian Institution.

Early Dageurotypes by African American photographers James P. Ball, Glenalvin Goodridge, and Augustus Washington are part of a new display at the Smithsonian Institution.

Beatrice L. Warde, a typographer and author of the famous short essays: "This is a Printing Office" and "The Crystal Goblet, should have been included in Tom Hanks' 2021 film News of the World. In the original book of the same name, the "captain" quotes Warde at length. For more about Warde, see this article from the American Printing History Association.

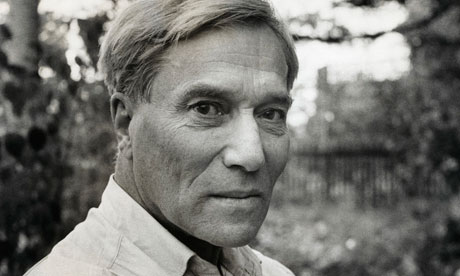

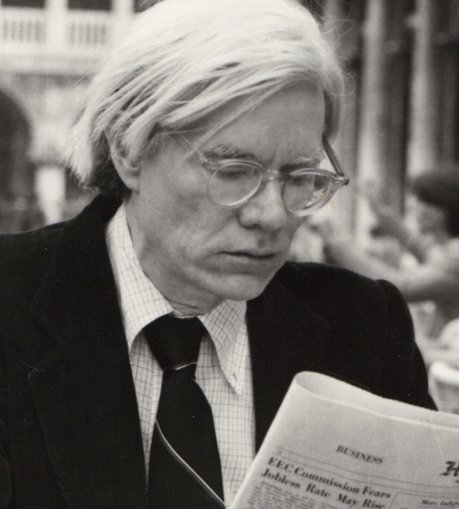

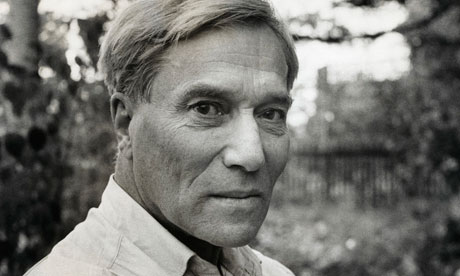

Bruno Barbey a photographer for the Magnum Photos agency, known as a powerful visual architect, and perhaps one of the last great war photographers in the humane style of Robert Capa, died at age 79 in France Nov. 9, 2020. He was 79 years old.

Ida B Wells, a black journalist and women's suffrage leader in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, is remembered in this mosaic at Union train station at the US Capitol in Washington DC.

Ida B Wells, a black journalist and women's suffrage leader in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, is remembered in this mosaic at Union train station at the US Capitol in Washington DC.

Dorothea Lange photo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, New York shows a remarkable and enduring photojournalist.

Dorothea Lange photo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, New York shows a remarkable and enduring photojournalist.

William Monroe Trotter, a radical black newspaperman, is profiled in the Nov. 25, 2019 issue of the New Yorker. Trotter rejected the view that racial equality could come in stages.

William Yukon Chang’s monthly Chinese-American Times chronicled life, culture and politics in the Chinese community in New York, according to his New York Times obituary.

William Yukon Chang’s monthly Chinese-American Times chronicled life, culture and politics in the Chinese community in New York, according to his New York Times obituary.

Margaret Bourke-White photos are featured in the Atlantic Magazine in August, 2019.

Margaret Bourke-White photos are featured in the Atlantic Magazine in August, 2019.

Tank Man by Jeff Widener is one of 100 greatest photos described in a Time Magazine online feature.

Tank Man by Jeff Widener is one of 100 greatest photos described in a Time Magazine online feature.

Harold Edgerton, a pioneer of high speed photography, is remembered in this July 2019 Smithsonian video about filming atomic explosions.

Harold Edgerton, a pioneer of high speed photography, is remembered in this July 2019 Smithsonian video about filming atomic explosions.

Evelyn Berezin, invented the word processor in the 1960s to lighten the load of secretaries worldwide. She is remembered in this New York Times obit.

Evelyn Berezin, invented the word processor in the 1960s to lighten the load of secretaries worldwide. She is remembered in this New York Times obit.

PBS archives will be opened at the University of Georgia. According to a July, 2018 article in the Red & Black, around 4,000 hours of PBS programs from 1941-1999 will be released. The programs were once submitted for Peabody Awards.

PBS archives will be opened at the University of Georgia. According to a July, 2018 article in the Red & Black, around 4,000 hours of PBS programs from 1941-1999 will be released. The programs were once submitted for Peabody Awards.

Virtual Reality will have the same emotional effect on audiences that photography did in the 19th century, says Stanford professor Jeremy Bailenson.

Virtual Reality will have the same emotional effect on audiences that photography did in the 19th century, says Stanford professor Jeremy Bailenson.

/https://public-media.smithsonianmag.com/filer/b4/ec/b4ec2608-cfe6-4187-a1de-7dbe856c1e11/lowell_thomas_magic_dials_1.jpg) Lowell Thomas, a man who helped define print and radio journalism in the early to mid-20th century, is profiled in the Smithsonian Magazine, June, 2017.

Lowell Thomas, a man who helped define print and radio journalism in the early to mid-20th century, is profiled in the Smithsonian Magazine, June, 2017.

Fake news isn't so new after all. In "Techniques of 19th-century fake news reporter," Petra S. McGillen of Dartmouth tells the story of Theodor Fontane, a correspondent for Kreuzzeitung of Berlin, who covered London's Tooley Street Fire of 1861 without leaving Germany.

Clare Hollingworth, the reporter who broke the news about the start of WWII from Poland, is eulogized in this Jan. 2017 obituary.

Clare Hollingworth, the reporter who broke the news about the start of WWII from Poland, is eulogized in this Jan. 2017 obituary.

Ring Lardner a famous sports columnist in the early 20th century, is profiled in a 2017 book by NPR's Ron Rapoport.

Ring Lardner a famous sports columnist in the early 20th century, is profiled in a 2017 book by NPR's Ron Rapoport.

TV and US Civil Rights A 17-minute television talk by Medgar Evers on May 20, 1963 -- which led to his assassination -- also resulted in a fight over a TV station license in a case that changed American Television. The NARA and the Zinn project have the story.

TV and US Civil Rights A 17-minute television talk by Medgar Evers on May 20, 1963 -- which led to his assassination -- also resulted in a fight over a TV station license in a case that changed American Television. The NARA and the Zinn project have the story.

Rome, Open City by Roberto Rossollini is celebrated on its 70th anniversary.

Rome, Open City by Roberto Rossollini is celebrated on its 70th anniversary.

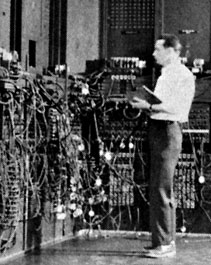

Unrecognized women of ENIAC are finally getting some recognition thanks to the ENIAC programmers project.

Unrecognized women of ENIAC are finally getting some recognition thanks to the ENIAC programmers project.

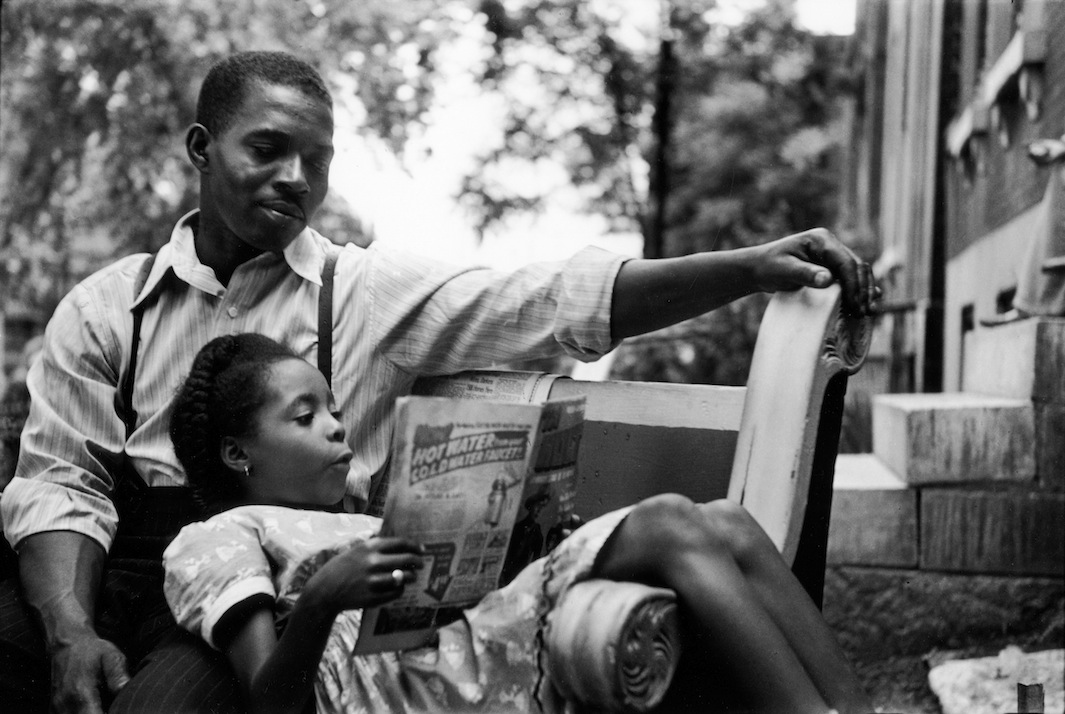

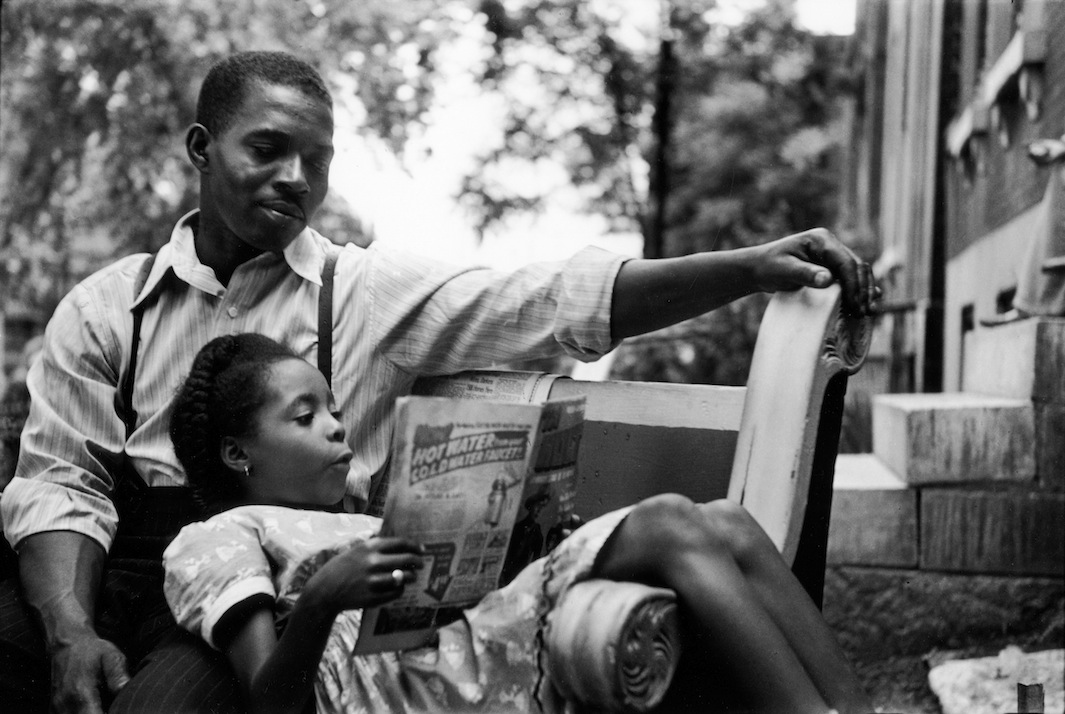

Lost Gordon Parks photos never ran in Life Magazine, on display now at Boston Fine Arts Museum.

Lost Gordon Parks photos never ran in Life Magazine, on display now at Boston Fine Arts Museum.

Birth of a Nation turns 100 NPR's excellent radio & web article about cinema director D.W. Griffith and the legacy of a virulently racist American film. Also noteworthy - Zinn project article by William Katz.

Birth of a Nation turns 100 NPR's excellent radio & web article about cinema director D.W. Griffith and the legacy of a virulently racist American film. Also noteworthy - Zinn project article by William Katz.

The Wipers Times, a humor publication from the least humorous situation ever -- the fighting trenches of WWI. Subject of an excellent movie in 2013.

The Wipers Times, a humor publication from the least humorous situation ever -- the fighting trenches of WWI. Subject of an excellent movie in 2013.

Ixnay on the Otography-fay Life in the trenches was no laughing matter for most. It was even illegal for soldiers to photograph during World War I, but George Hackney did it anyway. The photos came to light in November, 2014.

Ixnay on the Otography-fay Life in the trenches was no laughing matter for most. It was even illegal for soldiers to photograph during World War I, but George Hackney did it anyway. The photos came to light in November, 2014.

Nixon-Kennedy debates in September, 1960 brought the new power of media to bear on the old politics of the presidential campaigns, as this recent Chicago Tribune article reminds us.

Nixon-Kennedy debates in September, 1960 brought the new power of media to bear on the old politics of the presidential campaigns, as this recent Chicago Tribune article reminds us.

Dorothea Lange the amazing Depression-era photographer, is featured in a new PBS documentary in August, 2014.

Dorothea Lange the amazing Depression-era photographer, is featured in a new PBS documentary in August, 2014.

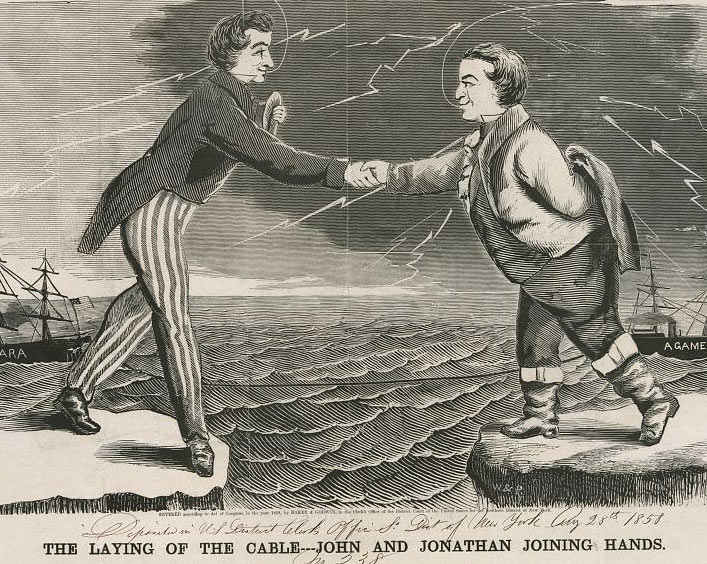

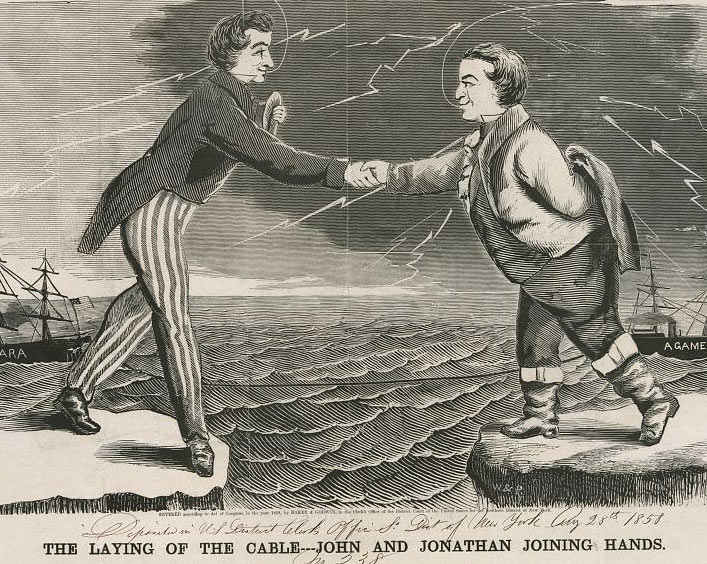

Too Fast for the Truth? The trans-Atlantic telegraph, first linking the US and the UK in 1858, generated the same kind of reaction and commentary about rapid communication that surrounded the Internet in the 1990s and micro-blogging in the 2000s. Adriene LaFrance reminds us of this in a great July 28, 2014 article in the Atlantic.

Too Fast for the Truth? The trans-Atlantic telegraph, first linking the US and the UK in 1858, generated the same kind of reaction and commentary about rapid communication that surrounded the Internet in the 1990s and micro-blogging in the 2000s. Adriene LaFrance reminds us of this in a great July 28, 2014 article in the Atlantic.

¶  Over 85,000 British Pathe newsreels with over 8 3,500 hours of news and entertainment, were made available by British Pathe company through YouTube in April, 2014.

Over 85,000 British Pathe newsreels with over 8 3,500 hours of news and entertainment, were made available by British Pathe company through YouTube in April, 2014.

¶ Harry McAlpin, the man who integrated the White House press corps, is featured in an Atlantic magazine article May 3.

Pranking is a great media tradition, says Kimbrew McLeod in a new book. (Yes, that's Ben Franklin in clown makeup).

¶ May 5 is the Chicago Defender's anniversary. Founded by Robert S. Abbott in 1905, the Defender has championed the cause of minorities for over a century.

Dr. Zhivago, the famed novel by Boris Pasternak about a Russian doctor in the 1917-1940 revolutionary time period, was banned in Russia. It was first published in Russian by the US Central Intelligence Agency, newly declassified documents reveal. (Guardian, April 9, 2014).

Dr. Zhivago, the famed novel by Boris Pasternak about a Russian doctor in the 1917-1940 revolutionary time period, was banned in Russia. It was first published in Russian by the US Central Intelligence Agency, newly declassified documents reveal. (Guardian, April 9, 2014).

Margaret Fuller biography by Megan Marshall wins a Pulitzer for 2014. Horace Greeley's famed editor was also remembered in a variety of radio programs, as found on Bob Stepno's JHeroes web site.

Margaret Fuller biography by Megan Marshall wins a Pulitzer for 2014. Horace Greeley's famed editor was also remembered in a variety of radio programs, as found on Bob Stepno's JHeroes web site.

¶ Ancient books online The Vatican and Oxford's Bodleian libraries began a project in December, 2013 to digitize their collections of ancient books in the interest of democratizing scholarship.

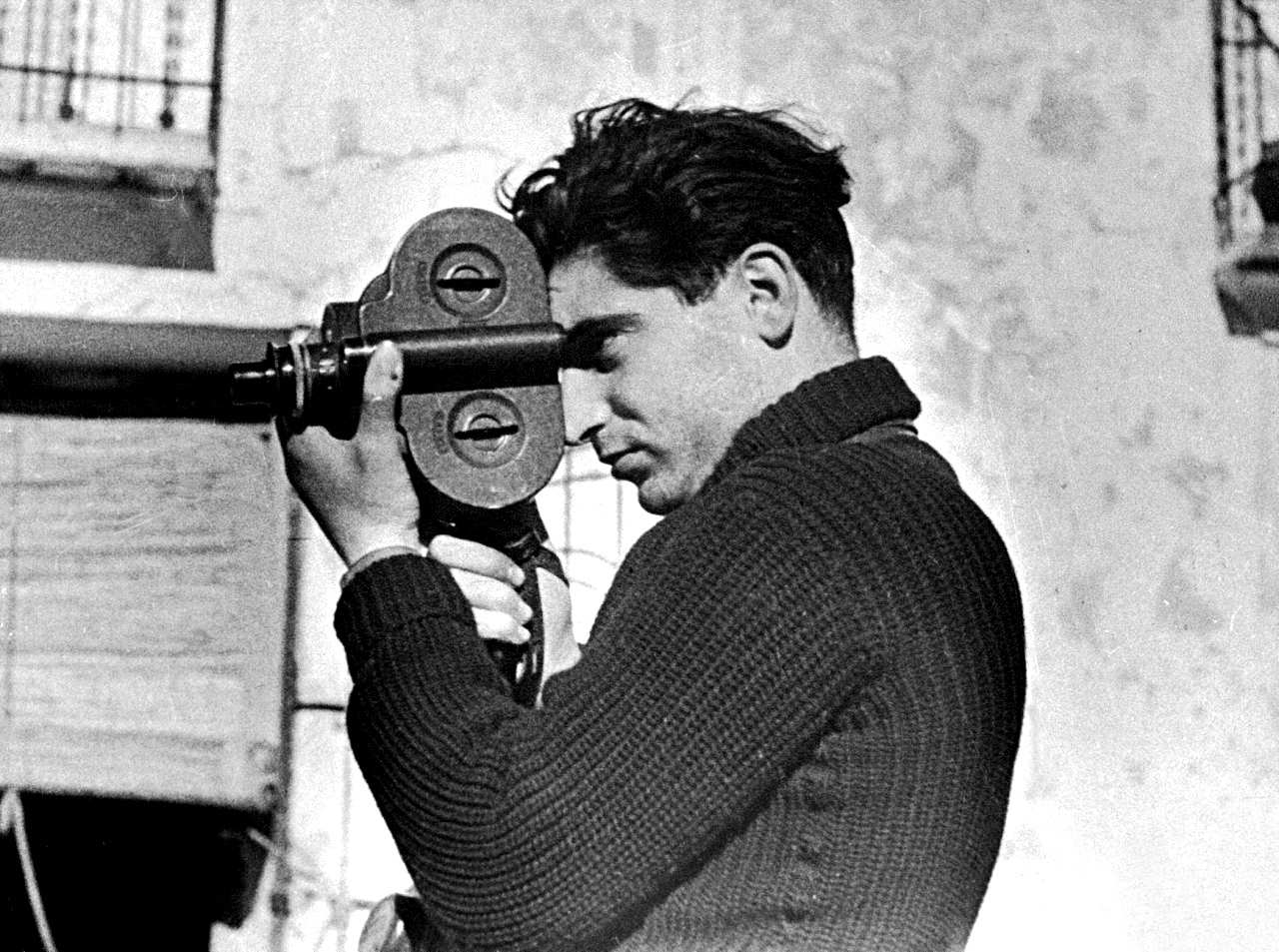

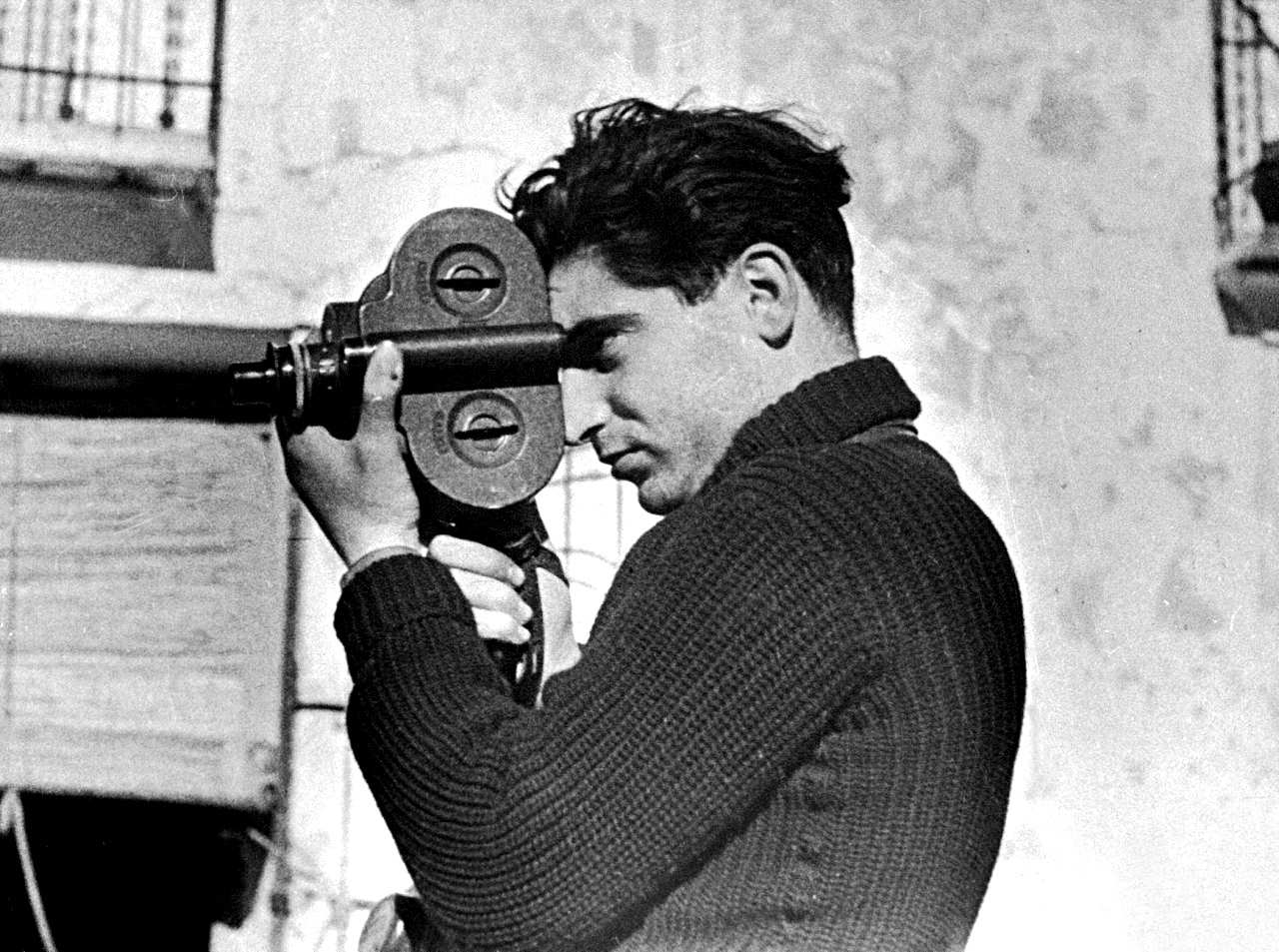

¶ 100th anniversary of Robert Capa's birth was Oct. 22, 2013. The famed Hungarian-American combat photographer once said: "If your pictures aren't good enough, you are not close enough." With that in mind, Magnum is running a "get closer" contest.

¶ Most silent films lost A US Library of Congress survey found that only 14 percent of silent films have survived over the past century. Washington Post, Dec. 4, 2013.

¶

The International Herald Tribune a Paris based newspaper, is no more. It will turn into the International New York Times on Oct. 15, 2013.

¶

Alan Turing a gay British mathe- matician who helped crack Nazi codes during WWII and who created many of the basic concepts and formulas for the modern functioning computer, was pardoned for his gay behavior, postumously, in Britain just before Christmas, 2013.

¶  Early Orson Wells film discovered in Italy, according to the New York Times, Aug. 7, 2013.

Early Orson Wells film discovered in Italy, according to the New York Times, Aug. 7, 2013.

¶ End of Kodak Great article in The Street by Joe Deaux about the final days at the photographic giant.

¶ Ben Franklin museum reopening in Philadelphia this August, 2013.

¶ Social networking in the 1600s involved coffee houses says Tom Standage in the International Herald Tribune June 22, 2013.

¶

Anti-Nazi documentary produced in 1934 by US filmmaker Neil Vanderbilt was rediscovered in Belgium this year. Story by Emily Greenhouse, May 21, 2013: The New Yorker.

¶

Cartoons that changed the world are posted from The Art of Controversy, previewed in Buzzfeed, May 2, 2013.

Cartoons that changed the world are posted from The Art of Controversy, previewed in Buzzfeed, May 2, 2013.

¶ Cincinnati Inquirer historical photo tour includes horseshoe-shaped copy desk (17) and linotype machines (12). March 6, 2013.

¶ Photographer Tony Vaccaro is celebrated by the New York Times. March 4, 2013.

¶

Thomas Nast is remembered by Jonathan Yardley at the Washington Post on Feb. 15, 2013. "The best and most widely known journalists of my youth — James Reston, Marquis Childs, Red Smith, even Walter Lippmann — are almost entirely forgotten outside the trade today and only dimly remembered inside it," Yardley says. Yet Nast's cartoons remain.

¶ Medgar Evers is honored by the Zinn project on Martin Luther King day in 2013. Evers was killed 50 years ago after an interview on what was then a virulently racist television station, WLBT, as noted in Revolutions in Communication. The assassination was not directly linked to the TV, but it started a Media Access Project investigation of the TV station's programming, which led to the loss of its license for failing to serve the public interest.

¶ Iranian newspapers in the 1960s were tightly controlled, like many today in China, Russia and the Middle East. That experience, says Karen Henderson in a Dec. 15 2012 Cleveland Plain Dealer column, reminds us of the importance of the press to democracy.

¶ The "Page Three Girl" is 42 years old on Nov. 27, 2012, according to women fighting sexism in the media who are staging protests in London. Their slogan: "Boobs are not news."

¶ Hollywood blacklist started 65 years ago on Nov. 25, 1947, the day after ten writers and directors (the Hollywood Ten) got citations for contempt of Congress. They had refused to name supposed fellow communists to the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) and claimed that they had rights under the U.S. Constitution.

¶ Elijah Lovejoy, a publisher in Alton Illinois, is killed by an angry pro-slavery mob on Nov. 7, 1835. The anniversary was noted by the Zinn Education Project.

"Imprudent, to defend the liberty of the press? ... Who invents this libel on his country?" -- Wendell Phillips, in speech given in Boston, one month after the November 7, 1837, slaying of abolitionist editor Elijah Lovejoy in Illinois. (Text from Project Gutenberg.)

¶ The Radical Camera, an exhibit opening in San Francisco in October, 2012, looks back to the age when photography was a social witness.

¶ Edward Curtis took photos of 19th century Native Americans. A new biography is out called Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher: the Epic Life and Immortal Photographs of Edward Curtis. The author tells NPR's Rachel Martin that Curtis discovered his first subject almost by accident.

James Gordon Bennett Jr. is remembered (although not very fondly) on the 125th anniversary of the International Herald Tribune in this New York Times article.

James Gordon Bennett Jr. is remembered (although not very fondly) on the 125th anniversary of the International Herald Tribune in this New York Times article.

¶ Gordon Parks is remembered in a photo gallery published by the New York Times. The former FSA photographer's work is up close, personal and brilliant. He would have been 100 this year.

¶ USA Today remembers the Nixon-Kennedy TV debates. They began Sept. 20, 1960 and are credited with changing political history.

¶ One hundred years ago, the Sacramento Bee depicted a prisoner on a pedestal to decry "soft" treatment of prisoners who should be executed. Today the Bee has a very different view.

¶ William Randolph Hearst died Aug. 14, 1951, and this year the San Francisco Chronicle commemorated the event by republishing an interesting poem he wrote. When our life has passed / And the river has run its course / It again goes back / O'er the selfsame track / To the mountain which was its source. Hearst, it seems, was no competition for other journalist / poets of the age, such as Rudyard Kipling or Joel Chandler Harris.

¶ So long to Karl Fleming, a Civil Rights reporter for Newsweek whose book, Son of the Rough South, helped chronicle the era. Fleming died in Los Angeles August 11, 2012. Also passing this summer: Helen Gurley Brown of Cosmopolitan magazine.

¶ Happy 150th birthday to Ida B. Wells, the intrepid reporter who exposed lynchings across the US South in the 1890s. Original work is here at Project Gutenberg; thanks also to the Zinn History Project for noticing.

¶ Satellite communications turned 50 years old on July 12. The first satellite transmissions took place in 1962 from Maine to Brittany, France. The signal contained images of the Statue of Liberty and the Eiffel Tower, remarks from President John F. Kennedy, and highlights of a Phillies-Cubs baseball game.

¶ The first photo on the web was posted twenty years ago at CERN in Switzerland. (SF Chronicle also covered it.)

¶ The history of the telephone is tucked away in an AT&T vault . in New Jersey.

¶ It's the end of the line for Minitel, the original French internet built in the 1980s.

¶ Alan Turing was the most significant contributor to computing in the 1930s and 40s. June 23, 2012, would have been his 100th birthday. Wired magazine has a good overview of the man and his impact.

¶ New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art is hosting an exhibit of China's printed images from the 8th - 20th centuries.

¶ The Library of Congress has published a book containing 200 years of political campaign posters. It's a treasure of visual communication history.

¶ Radio history's sentinel -- J. David Goldin -- is profiled in a Washington Post story May 3, 2012.

¶ Media history is celebrated in Google "doodles" . Over the past few years they have included Eadweard Muybridge , photographer Robert Doisneau , Louis Daguerre, and historian Ibn Khaldun.

¶ An old fashioned newspaper war has broken out in California, over a century-old conflict involving John Muir, a hydroelectric dam and the Hetch Hetchy canyon in the heart of Yosemite.

¶ The Hearst Corp. is 125 years old in March, 2012, and at least one newspaper, the San Francisco Chronicle, is celebrating.

¶ Beginning in late February 2012, the New York Times started to open its enormous photo archive.

¶ Stanford has cracked the door on its collection of Apple computer corporation archives, according to this Associated Press story. But its not enough for some people, who think the university should be doing more to make the archives public.

¶ New digital methods are starting to unlock the "vast collections" of sound recordings. A young Alexander Graham Bell is heard in some of the first Smithsonian releases on Dec. 12, 2011. Also in store -- great performances, speeches by world leaders, anthropological and linguistic studies, and many other voices from the past.

¶ Nov. 18 would have been Louis Daguerre's 224th birthday, and Google's search page celebrated with a one-day logo in commemoration.

¶ The London Science museum will build Charles Babbage's analytical engine, first envisioned in the 1830s, according to an article in the Nov. 8, 2011 New York Times.

¶ The 200th anniversary of Niles Register is celebrated by the Baltimore Sun and others.

¶ Aug. 25 is the anniversary of the Moon Hoax. Chicago Times columnist John Kass says it's his favorite hoax of all time.

¶ Aug. 24 is Wayzgoose -- a traditional holiday for printers, writers and the publishing industry.

¶ July 22 was the 100th anniversary of Marshall McLuhan's birth, and the communications and technology theorist celebrated by his most fervid admirers as Canada's greatest thinker of all time has emerged from the valley of darkness that closed around him in the last decade of his life. The Globe and Mail, July 15, 2011.

¶ The Pentagon Papers are being declassified, 40 years after they were published in the New York Times and Washington Post. Daniel Ellsberg says the Pentagon papers are still important today.

¶ Bob Woodward and Ben Bradley are welcomed at the Nixon library in April. The library's new exhibit portrayed journalists in a new and much more favorable light.

¶ Obama administration wants more international cooperation within the ICANN.

¶ Why is good news so hard to come by?The Montreal Gazette tackles the question.

¶ Peter Forsskål's 1759 Thoughts on Civil Liberty was recently published on the web. The Swedish philosopher had a major influence on European thought about freedom of information. The newly translated manuscript begins: "The more a man may live according to his own inclinations, the more he is free. Therefore, next to life itself, nothing could be more dear to man than freedom."

¶ Phil Meyer wonders whether it's already too late for the elite newspaper of the future.

¶ Kay Mills, author of "A Place in the News: From the Women's Pages to the Front Page" (1988), died Jan. 15, 2011.

¶ Fox Propagandists Degrade Journalism - Harold Meyerson, Washington Post. -- Rupert Murdoch's News Corp. "is the most sustained and coordinated dose of right-wing propaganda this country has ever seen. Father Coughlin, Joe McCarthy, George Wallace and their ilk were freelancers, much as Limbaugh is today. The choir at Fox News, by contrast, sings from Murdoch's hymnal."

¶ For Sarah Palin and Glen Beck, a McKinley Moment? Dana Milbank, Washington Post -- "One hundred and ten years ago, during another low point in the nation's political discourse, newspapers owned by William Randolph Hearst - who was angling for a presidential run in 1904 - published a pair of columns fantasizing about violence against President William McKinley. "

Black Press in the Civil War

Although the Civil War began as a conflict over secession, from the start most blacks saw it as an opportunity to free the enslaved with a Union victory. New York Times, March 13, 2014.

World Wide Web turns 25 Tim Berners Lee's original proposal for a World Wide Web turns 25 this March.

Stopping the presses The Wisconsin Journal is scrapping its old printing presses.

Margaret Bourke-White,

Margaret Bourke-White, Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin Eadweard Muybridge

Eadweard Muybridge Sinking of the USS Jeannette

Sinking of the USS Jeannette Media law and ethics

Media law and ethics

Early Dageurotypes

Early Dageurotypes

Ida B Wells

Ida B Wells Dorothea Lange

Dorothea Lange

William Yukon Chang’s

William Yukon Chang’s Margaret Bourke-White

Margaret Bourke-White  Tank Man

Tank Man  Harold Edgerton

Harold Edgerton Evelyn Berezin,

Evelyn Berezin, PBS archives

PBS archives Virtual Reality

Virtual Reality /https://public-media.smithsonianmag.com/filer/b4/ec/b4ec2608-cfe6-4187-a1de-7dbe856c1e11/lowell_thomas_magic_dials_1.jpg) Lowell Thomas

Lowell Thomas

Clare Hollingworth

Clare Hollingworth Ring Lardner

Ring Lardner  TV and US Civil Rights

TV and US Civil Rights  Unrecognized women of ENIAC

Unrecognized women of ENIAC Lost Gordon Parks photos

Lost Gordon Parks photos Birth of a Nation turns 100

Birth of a Nation turns 100 The Wipers Times,

The Wipers Times,  Ixnay on the Otography-fay

Ixnay on the Otography-fay Nixon-Kennedy debates

Nixon-Kennedy debates  Dorothea Lange

Dorothea Lange  Too Fast for the Truth?

Too Fast for the Truth?

Dr. Zhivago

Dr. Zhivago Margaret Fuller

Margaret Fuller

Early Orson Wells film

Early Orson Wells film

Cartoons that changed the world

Cartoons that changed the world

James Gordon Bennett Jr.

James Gordon Bennett Jr.