In the fall of 1989, Tomas Jane, a student at the University of Ostrava, risked his life for what would become known as the Velvet Revolution.

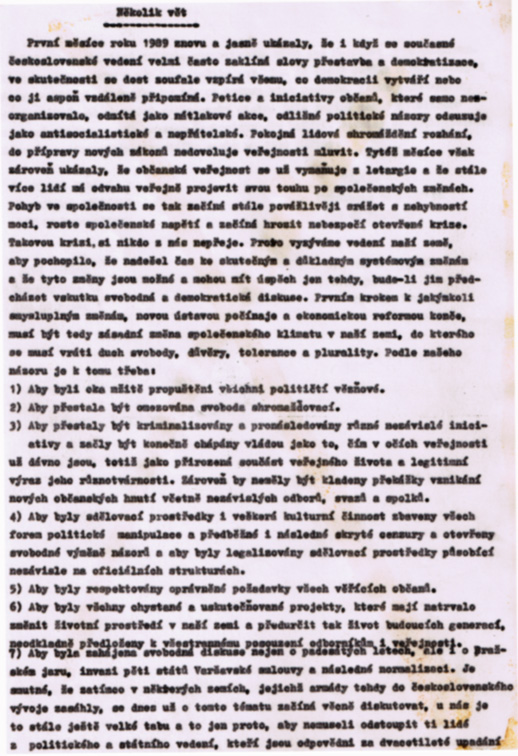

About twice a week, the computer science student took a 370 kilometer train trip to Prague and back to Ostrava, carrying suitcases packed with subversive street literature.

He knew that if he was discovered by the police, he could face years of imprisonment, or worse. But as the Velvet Revolution gathered steam, he also knew he was on the right side of history.

Jane was one of a handful of people who volunteered for these missions so that political reform groups could share the same street pamphlets and cartoons in all Czechoslovakia’s major cities.

Because he was aware of the historical nature of his work, Jane decided he would save one or two of the pamphlets after every trip. And then, in the fall of 1991, concerned about a possible counter-revolution, he brought the pamphlets out on a visit to the US. He left his collection with Prof. Kovarik, who would later be the author of Revolutions in Communication and this book-related web site.

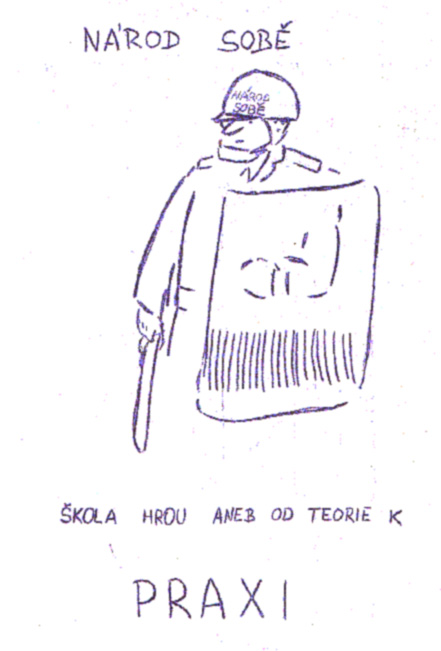

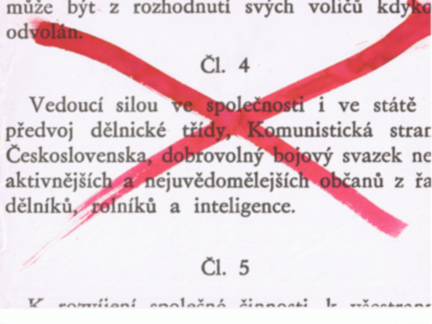

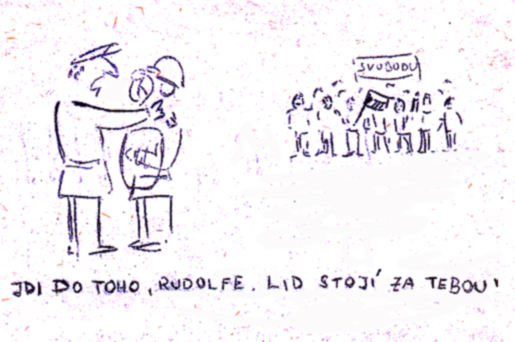

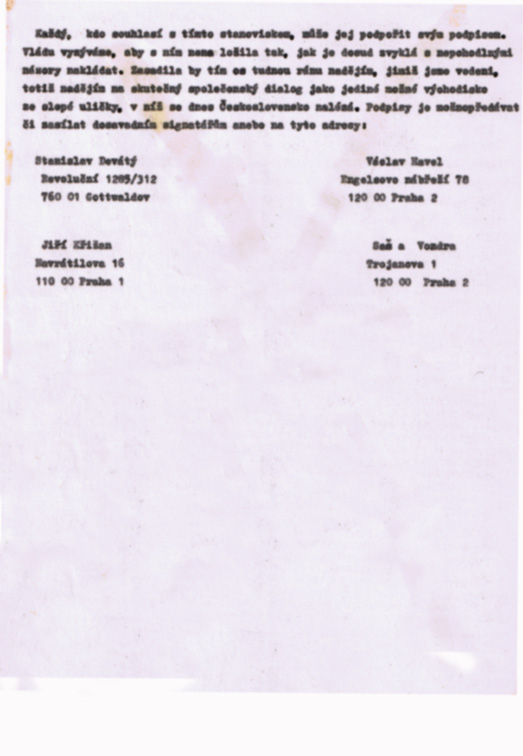

Most of these cartoons and manifestos were printed on crude mimeograph machines — the kind that were found in thousands of schools and universities in order to create handouts and tests. These old copying machines were everywhere, and they were impossible for the Soviets to control.

These cartoons and pamphlets are examples of the way that political or social revolutions often borrow from older communications technologies in order to circumvent censorship.

Similarly, hand-written copies of forbidden books, called “samizdats” (same-as-that) were a feature of resistance to Soviet communism throughout Russia and Eastern Europe in the 1970s and 80s; audio cassette tapes were used for revolutionary messages during the Iranian revolution in the late 1970s; and wall posters were a major feature of student demonstrations in China in 1989.

All of these cartoons, street manifestos, samizdats and posters also convey something of the enduring human spirit, infused with enduring humor and a long view of history, that refuses to submit to oppression.

Links to Velvet Revolution sites:

The Velvet Revolution — International Center on Nonviolent Conflict, By Lester Kurtz, 2008

Free media in the Velvet Revolution – video from the Wilson Center, 2014

Open Society catalog search – Velvet Revolution

Reflecting on media coverage of the Velvet Revolution (AGBU Armenia, 2018)

The Velvet Revolution and its children