When film making emerged from its experimental phase in the early years of the 20th century, most silent movies featured visualizations of then-familiar themes, such as Jules Verne’s moon trip or depictions of religious figures or educational topics. As the topics became riskier—burglaries, train robberies, or stolen kiss in a shoe store—the themes became more threatening to the old cultural elites. Even the fact that young people were congregating in dark, crowded theaters — instead of well-lit churches or lecture halls — was alarming to advocates of refined culture, especially in the older generation. Some, like social reformer Jane Addams, worried that the “corrupt” art of movies was replacing “true” drama, which was needed to satisfy the craving for a higher conception of life. If young people “forecast their rose colored future only in a house of dreams,” Addams said, society would founder on a “skepticism of life’s value.”

A more immediate cause for trouble was the carnival atmosphere and sexually suggestive songs and dances found in movie districts. The showdown came on Christmas Day, 1908, in New York. Reacting to testimony from religious groups that movies involved “profit from the corruption of the minds of children,” the mayor revoked the licenses of 540 motion picture halls. Mayors in other cities quickly followed suit. In response, movie theater owners formed an association and sued the city. “This sort of treatment can go in Russia, but it can’t go in this country,” one of the theater owners said. By January 7, 1909, the moralists lost the first round when the courts ruled that the mayor had no power to close all movie theaters, even though reasonable regulations over fire hazards and indecency could be imposed.

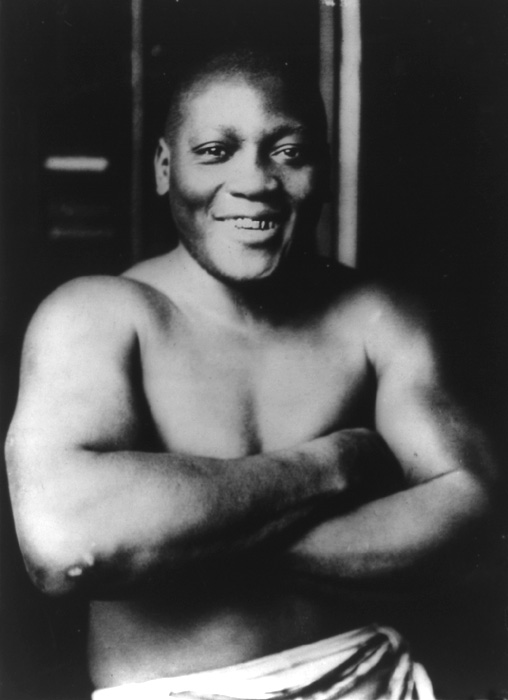

Another round in the early fight over film censorship involved the first African-American heavyweight boxing champion, Jack Johnson. In a well-publicized July 1910 match, Johnson won the title, beating James Jeffries, a white boxer who had been styled as the “great white hope.” A 1910 film showing the boxing match and Johnson’s victory led to rioting in many US cities and at least eight deaths. Historian Robert Niemi called it an “exceedingly ugly episode in the appalling annals of American racial bigotry.” The film’s ideological significance alarmed racists in Congress who passed a federal ban on interstate sales of all boxing films in 1912.

The topic of prostitution led to another controversy over films a few years later. Film makers used the pretext of a 1912 report on vice in New York to show supposedly moralistic films depicting the evils of the “white slave trade.” These “vice films” outraged moralists in the media. Films like Damaged Goods, The House of Bondage and Guilty Man “will pour oil upon the flames of vice,” the New York Times said. The contrast with newspapers is interesting. When newspaper publishers used the same sensationalistic tactics a generation before, they were rewarded. William T. Stead, who published London’s Pall Mall Gazette, made an enormous profit exposing the “virtual slave trade” of London in 1883, treating the subject as a moral lesson but providing plenty of salacious detail. Pulitzer and Hearst also used the cloak of morality to expose shocking tales of vice and intrigue. But film was new, and as a New York judge said in 1913, “tends to deprave the morals of those whose minds are open to such influences.”

Although film makers said they were fighting for freedom of speech, newspapers reported the issue in terms of films being “withdrawn” rather than “censored.” Around this time, Thomas Edison, a social conservative who owned many US patents for film cameras and projectors, attempted to control both the business and its cultural impacts by forming the Motion Picture Patents Company in 1908.

Like other monopolies at the time, the MPPC was known as a “trust.” The MPPC “Edison Trust” included US filmmakers like Biograph and Vitagraph, and French filmmakers like Méliès and Pathé. But it did not include independent US film makers. The MPPC tried to stabilize a chaotic industry by setting standards and sharing patents, but as a monopoly, they were also able to keep independents from exhibiting in theaters or using their equipment.

At the same time, the MPPC also formed a national censorship board to exclude anything that seemed immoral, leading the crusade for “moral purification” of movies. But like other technological monopolies, the Edison Trust’s attempt to control the business failed. The independents, especially the founders of Universal, Paramount and Twentieth Century Fox studios, moved away from the East coast to California, where mild weather and distance from the Edison company allowed feature film expansion. Then too, the dominance of European films from Méliès and Pathé ended abruptly with the outbreak of World War I in 1914.

The emerging film industry went to the courts for protection. In 1915, independent producers, contending that Edison’s MPPC was an illegal monopoly, won a Supreme Court decision in United States v. Motion Picture Patents Company. That same year, the court also eased the fears of social conservatives in a related case, Mutual Film v. Industrial Commission of Ohio, ruling that films are not protected by the First Amendment. States were then free to set standards and film censorship boards of their own, and many did.

Fearing a patchwork of censorship, and reacting to a series of Hollywood scandals fanned by Hearst newspapers, the film industry formed the Motion Pictures Production and Distributors Association in 1922 (which became the Motion Picture Association of America in 1945). Headed by Will H. Hayes, the MPAA fought both federal proposals for film censorship and critics within the movie industry who charged that it was a way to establish “complete monopoly” of major film producers over independent theater owners. This fight over control of theaters began an antitrust lawsuit that was finally settled in the United States v. Paramount case two decades later.

Pre-Code Hollywood films were experimental and frequently risque, as seen in this still from the 1931 film Safe In Hell.

Between around 1928 and 1934, the advent of sound, along with the widespread corruption associated with Prohibition laws, led to a fascination with crime, sex and violence in what were known as “Pre-Code” Hollywood films. The reaction was the creation (in 1930) and then strong enforcement of the Hollywood Production Code (starting in 1934) under the MPPDA.

The code said: “No picture shall be produced that will lower the moral standards of those who see it.” Under the code, criminals could never win, and partial nudity, steamy sex scenes and homosexuality were all strictly banned. The code survived numerous court challenges until the 1960s. And yet, as a product of its times, the code did not prohibit narratives encouraging racism or antisemitism that are considered grossly immoral in the late twentieth century.

The code permitted church and other moral authorities to exert enormous influence over film from the mid-1930s to the mid-1950s. It was struck down by the US Supreme Court in Burstyn v Wilson, a 1952 case involving censorship of “The Miracle,” a short Italian film by Roberto Rossellini that questioned the concept of a virgin birth and was opposed by the Catholic Church in the US.

A rating system replaced the code in the 1960s, and it is still in existence and still administered by the MPAA (G, PG, PG-13, R and NC-17). On the plus side, the rating system address the concerns of parents who wanted to avoid having children exposed to adult ideas and themes.

However, the code has also made it more difficult for independent filmmakers to compete against the big studios and it has contributed to the Hollywood domination of international cinema well into the twenty-first century. Modern critics contend that a secretive private ratings system, without an open appeals process, still amounts to a form of censorship and discrimination in favor of major studios against independent film makers.

Politics as well as morality could also be a source of censorship. For example, a Paramount newsreel film of the Republic Steel Strike on May 30, 1937, in which 10 workers were killed, was banned for contributing to additional labor unrest.

Other resources on censorship:

- Beacon for Freedom of Expression — An international source of information about censorship.

- Censorship — European History Online.

- Gregory Black, Hollywood Censored: Morality Codes, Catholics, and the Movies (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge U. Press, 1994), 30.

- The Celluloid Closet