Humans have been writing for thousands of years, but the techniques differ across time and between cultures.

The goal in these exercises is to try out the different techniques and consider their immediate advantages and disadvantages. Also, think about how flexible writing systems (like the ones we’ll try here) worked for religious, commercial and bureaucratic communications. How much of an improvement were they over durable media such as stone carving or clay tablets?

Lecture 1 — Prof. Kovarik –G1.0.Intro (pdf)

Lecture 2 – Airaghi.Hieroglyphics (pdf)

Historical theory: We will consider Harold Innis‘ theories about durable vs flexible media systems and their “bias” towards time or space; Walter Ong’s theories about oral cultures and the “alphabet effect“; and Marshall McLuhan’s idea that “the medium is the message,” which is to say, media technologies differ in the way they shape and contain messages.

Lab sections:

Lab sections:

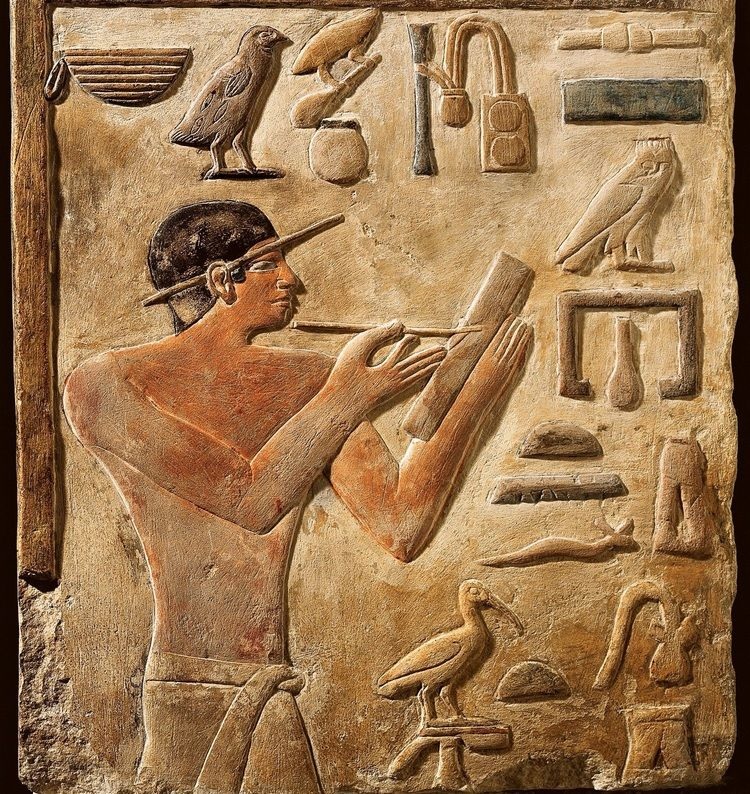

- Egyptian hieroglyphs —

Video 1: British Museum on reading hieroglyphs.

Reference: Long list of hieroglyphs

Hieroglyphs partial list (from Catharine Roehrig’s book Fun with Hieroglyphs, published by the Metropolitan Museum of Art).

Hands on Media History cartouche (vertical and horizontal)

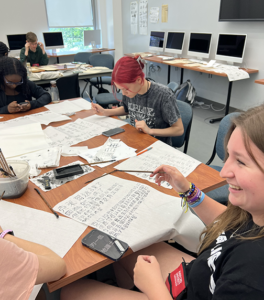

Materials: We used hieroglyph stamps from the Roehrig book (and of course needed stamp pads) along with papyrus paper for Egyptian hieroglyphics - Chinese Zhenshu calligraphy —

Video 2: Using brush and ink stick

Reference: The Four Treasures of the Study (materials); and the Eight Principles of Yong (brush techniques). (Both via Wikipedia)

Materials: Brush, ink stick, ink stone, and rice paper.

- European manuscript culture —

Women in book history / using quill pens

Video 3: How to prepare and use a quill pen.

Reference: Quill pens (Wikipedia)

Materials: Goose or turkey quill feathers and parchment or thick paper - Paper making information is available from Wake Forest University.

Symbols and the origins of writing

Also: Background on the history of written communication.

Symbolic communication goes back many thousands of years, and we are still learning about its origins. In late June, 2023, scientists reported finding 57,000-year-old Neanderthal cave carvings and engravings.

Ice Age carvings from ivory and bone go back over 45,000 years in some cases. One striking example of a carving is the Venus of Willendorf dated to about 24,000 years ago. This sculpture and similar objects are not tools—they are intentionally carved and painted objects that are worn and polished by repeated handling over a long period.

We don’t know what role these objects played in the oral cultures in this prehistoric time. We can guess that a carving of a mother goddess may have related to fertility, and that a carving of a horse or a painting of a bison might have involved pre-hunting rituals. It’s also possible that the objects had some use within the group decision-making process, perhaps being passed around from speaker to speaker to indicate who had the privilege of speaking at a particular moment.

We don’t know what role these objects played in the oral cultures in this prehistoric time. We can guess that a carving of a mother goddess may have related to fertility, and that a carving of a horse or a painting of a bison might have involved pre-hunting rituals. It’s also possible that the objects had some use within the group decision-making process, perhaps being passed around from speaker to speaker to indicate who had the privilege of speaking at a particular moment.

Another class of symbols before printing involved seals and stamps for making impressions on clay, wax, papyrus, or fabrics. The purpose might have been decorative or authoritative, for example, to authenticate a document.

Cylinder seal and its impression on a clay tablet.

Roman historian Marcus Terentius Varro was said to have inserted images of several hundred illustrious persons by the aid of “a certain invention,” thus “saving their features from oblivion” and “making them known over the wide world.” The invention was probably woodblock printing or some kind of embossing. “As the inventor of a benefit which will fill even the gods with jealousy, he has clothed these persons with immortality,” Roman historian Pliny the Elder said cryptically.

While language is pre-wired in the human brain, writing is not. It had to be invented, and because of that, we often see writing as the first communications revolution that extended natural human abilities.

The first type of writing is thought to have involved the use of clay tokens for keeping track of grain and livestock. This early system dates back to 8500 BCE and to ancient Mesopotamia, and possibly just as early in ancient China.

These clay tokens were three-dimensional solid shapes like spheres, cones, and cylinders kept in clay boxes. They were meant to keep track of resources like units of grain and numbers of oxen, but at some point along the way, the system changed from keeping 100 clay oxen tokens in a box to writing a symbol for 100 along with the symbol for ox. Increasing trade led to a further need to simplify accounting, which spurred the development of writing.

Hieroglyphic writing emerged in Egypt around 3200 BCE, while formal Chinese writing was formalized around 1500 to 1200 BCE, although some early primitive writing apparently goes back to 6600 BCE. Along with cuneiform in Mesopotamia, these are thought to be the earliest writing systems.

Hieroglyphic writing emerged in Egypt around 3200 BCE, while formal Chinese writing was formalized around 1500 to 1200 BCE, although some early primitive writing apparently goes back to 6600 BCE. Along with cuneiform in Mesopotamia, these are thought to be the earliest writing systems.

Egyptian hieroglyphs and Chinese written languages began as logographic systems — that is, they represented familiar objects through a logo or picture of the object. A circle with a dot is the hieroglyph for the sun. However, there are hieroglyphs for syllables as well as alphabetic characters for single sounds.

The first alphabetic writing dates back to about 1800 bce from the Sinai Peninsula, but its elements seem to have been derived from Egyptian hieroglyphs adapted to language. The alphabet was a democratization of writing, and alphabets in the world today are derived from that original Semitic script.

The introduction of writing brought about a change in thinking for previously oral cultures. Historian Walter Ong noted that writing and printing introduced a more linear, sequential and homogeneous approach to thinking, in contrast to the older oral cultures of heroic epics, songs, and tales told by firelight (Ong 2002). Similarly, theorist Walter Benjamin saw mechanical reproduction of writing and art as contributing to a loss of social ritual and personal identity (Benjamin et al. 2008).

Plato famously warned in his dialogue Phaedrus that writing would lead to the loss of memory, which was one of the key elements (canons) of rhetoric:

If men learn this [writing], it will implant forgetfulness in their souls; they will cease to exercise memory because they rely on that which is written … It is no true wisdom that you offer your disciples, but only its semblance, for by telling them of many things without teaching them, you will make them seem to know much, while for the most part they know nothing, and as men filled, not with wisdom but with the conceit of wisdom, they will be a burden to their fellows.

Although specialized messengers could be trained to remember complex messages to be carried over time and distance, scribes with flexible media could more easily speed messages through empires, and this was vital to their success, according to historian Harold Innis.

Types of Written Language

Logographic: Form of language using symbols of real objects. For example, the Egyptian hieroglyph for duck looks like a duck, and the Chinese logogram 山 stands for mountain.

Logographic: Form of language using symbols of real objects. For example, the Egyptian hieroglyph for duck looks like a duck, and the Chinese logogram 山 stands for mountain.

Syllabaric: In which certain symbols stand for syllables. Complex logographic systems like Chinese, or those derived from logographic systems (like Japanese), have characters that stand for syllables as well as logographic characters.

Alphabetic: Where individual characters stand for phonemes (sounds) of the spoken language. For instance, English is based on the Latin alphabet (A, B, C, D …); Russian is based on the Cyrillic script ( A, B, Г, Д, …).

Symbolic and visual communication was also embedded in medieval and Renaissance architecture, sculpture, and painting. These iconic images were the news and educational vehicles of the day. People of the twelfth century would visit Chartres Cathedral to learn religious stories in the same way that scholars would flock to Oxford or the Sorbonne and read books in the following centuries.

Symbolic and visual communication was also embedded in medieval and Renaissance architecture, sculpture, and painting. These iconic images were the news and educational vehicles of the day. People of the twelfth century would visit Chartres Cathedral to learn religious stories in the same way that scholars would flock to Oxford or the Sorbonne and read books in the following centuries.

An important point about these forms of written language is that alphabets

can communicate billions of ideas with only about two dozen symbols. In contrast, logographic and syllabaric systems require thousands of symbols. This is not a problem in a manuscript culture, but it was a crucial difference in the development of mass communication through printing, since it is difficult to create and organize thousands of separate permanent symbols to be used in a printing press. So, for example, even though Bi Sheng invented printing with moveable ceramic type in China in 1041–8—about 500 years before Johannes Gutenberg used metal type—the system was too cumbersome to be create a revolution in communication, and Chinese printers continued to use carved wooden blocks until the modern era.

Writing grew naturally from the elite, in early cultures, to the upper and then middle classes in the Greek and Roman empires. Literacy faded in Europe during the early medieval period, around 500–1000 CE, when reading and writing were almost exclusively the province of the clergy. Charlemagne, Frederic Barbarosa, most popes, and most kings and queens of the period were not even able to sign their names. Writing was held in such contempt that when the Crusaders took Constantinople in 1204, “they exposed to public ridicule the pens and ink stands that they found in the conquered city as the ignoble arms of a contemptible race of students” (De Vinne 1877).

At the same time, literacy was nearly universal in other cultures, for example, in Arab nations in the 900–1500 period when great centers of learning flourished from Timbuktu, Mali, to Baghdad, Iraq. Many of the great literary treasures of Greek and Roman civilizations were saved by the literate Arab culture of this era, and appreciated once again in Renaissance Europe only after around 1200–1300 CE.

Writing, said media scholar Wilbur Schramm, is what allowed humans to conserve intellectual resources, to preserve the legacy without having to keep all the details in their heads, and to devote energy to advancing knowledge. This had an enormous effect on human life. “With language and writing in hand, humans had paid the tuition for their own education,” Schramm said. Mass media, beginning with the printing revolution, would become their open university.

Along with language, written communication may require four basic items: an instrument, a carrier (medium), a vehicle, and a way to prepare the vehicle. In Chinese traditional culture these are called the “Four Treasures of the Study,” and the specific examples are the brush, the paper, the ink, and the ink-stone.

The earliest civilizations tended to use durable materials, such as clay and stone, to keep track of accounts and send messages through long durations of time.

Stone is the most durable medium but not at all flexible. Carvings and paintings on stone are found throughout the ages, in all parts of the world, as permanent records of empires and faiths. The best-known example is the Rosetta Stone, a decree involving an Egyptian king’s divinity, carved on a granite-like rock in 196 bce and discovered in 1799 by Pierre-François Bouchard, a soldier who was part of the Napoleonic expedition to Egypt. Because the decree was carved in three languages—Hieroglyphic, late Egyptian (Demotic), and ancient Greek—it opened the door for the translation of hieroglyphics.

Clay was the simplest and earliest writing medium. Between half a million and two million clay tablets and markers from ancient Mesopotamia have been recovered in the modern era. Scribes once used a wedge-shaped stylus to

make marks in clay, which was then fired in kilns to create a permanent record; or the clay could be recycled for reuse later if the record was not permanent. Early Mesopotamian writing is called Cuneiform, which is Latin for “wedge shaped.” Cuneiform translation began in 1835 when Henry Rawlinson visited an archeological site in what is now eastern Iran to see the Bisotun (or Behistun) inscriptions. He realized that, like the Rosetta Stone, the inscriptions consisted of three identical texts.

Papyrus is a plant native to the wetlands of the Nile valley of Egypt. It was originally used by the classical civilizations of Egypt, Greece, and Rome. It is pounded flat and laid crossways to create a sheet of papyrus paper, and is effective because the plant has a glue-like material that holds the sheet together. The first examples are from about 2550 BCE.

Wax tablets on a wooden backing were often used in ancient Greece and Rome for writing that was temporary. Two tablets could be hinged together to protect the wax, which is an idea that probably led to the codex (book).

Parchment was a widely used medium in the ancient Roman Empire that employed the skin of sheep, goats, cows, or other animals. Unlike leather, which is tanned, parchment membranes are soaked and scraped thin to provide a high quality writing surface. The best parchment was vellum, usually from calfskin.

Silk was used since at least the second century bce in China for transmitting and preserving important religious and civil texts. Silk was flexible but very expensive, and its use was highly restricted to royalty.

Paper is traditionally said to have been discovered by Ts’ai Lun, a Chinese monk who observed paper wasps making a nest around 105 ce. The technique is a huge improvement over hard-to-prepare animal hides, brittle papyrus, and expensive silk. Finely chopped wood or rag fibers are mixed with glue in a vat, and then poured over a screen. The thin layer of fibers on the screen dries into paper.

Cheap paper became widely available around 1400 in Europe and was apparently in surplus by the mid-1400s. One contributing factor may have been the increased number of linen rags from cast-off clothing, which people needed to weather the winters in the Little Ice Age (c. 1315–1800).

Scrolls: Parchment, papyrus or paper rolled up on either end. Information is kept sequentially in a scroll; it can’t be accessed at random like a codex (book).

Codex (book): The word comes from the Latin for “caudex,” meaning the trunk of a tree. A codex is a group of pages of paper or parchment that is gathered from one side at the back. A codex is a book if the pages are separate, but older forms of codex may also have pages folded in series, like an accordion.

Communication and the History of Technology

Human use of tools is often seen as one of the characteristics that distinguishes us as a species. The historical study of technology and culture involves questions about the creation, diffusion and social impacts of tools and techniques to extend human power for agriculture, communication, energy, transportation, warfare, and other fields.

Which of these techniques and fields have had more influence over civilization is a source of ongoing debate and exploration over the centuries. Technological progress was the primary factor driving civilization, according to some early anthropologists, while others have seen the use of energy or the accumulation of information as central to cultural development.

Mass media technology has had a special influence, according to many historians. We need to ask how this influence has been evident in the past and what is its likely path in the future.

Harold Innis, Marshall McLuhan, and media technologies

Two mid-twentieth-century historians most concerned with media technologies and their place in history were Harold Innis and Marshall McLuhan.

Harold Innis (1894–1952) was an economic historian who said that Western civilization has been profoundly influenced by communication technologies, while Marshall McLuhan (1911–80) was a media critic who was strongly influenced by Innis and also put communication at the center of history and social life.

Innis had the idea that civilizations using durable media tended to be oriented toward time and religious orthodoxy (Babylon), while, on the other hand, cultures with flexible media (Rome, Greece, modern) were oriented toward control of space and a secular approach to life.

The concepts of time and space reflect the significance of media to civilization. Media that emphasize time are those durable in character such as parchment, clay and stone. The heavy materials are suited to the development of architecture and sculpture. Media that emphasize space are apt to be less durable and light in character such as papyrus and paper. The latter are suited to wide areas in administration and trade.

What this implies is both obvious and far-reaching. Clearly, detailed instructions and correspondence over a distance can take place only if medium is light and flexible enough to carry the message. A dozen letters of credit on parchment are far easier to carry than a dozen clay tablets. But rather less obviously, the qualities of media flexibility and durability may be important elements in the way a civilization is organized. The fact that you can have letters of credit means you can have a banking system with branches across large distances.

McLuhan extended Innis’s ideas, which he summed up in the statement, “The medium is the message.” By that, McLuhan meant that the kind of communication media—print, imaging, broadcasting, or computing—has a strong influence not only on the message itself, but also on the type of thinking and the development of the culture creating the messages. A literate print culture is very different from a visual or radio or television culture, McLuhan said.

Many people thought literate culture would be weakened by television and radio, just as generations before thought that religious oral cultures would be weakened by printing. McLuhan was relatively optimistic, although not utopian, about media technology. Digitally controlled international broadcast media were connecting print and imaging and radio and television through satellites in the 1950s and 1960s, when he was active, and the convergence of media cultures to extend human perceptions would expand exponentially, leading us into a twenty-first-century “global village.” This would not lead to universal peace and happiness, he believed, but it would allow humanity to approach a greater degree of cultural maturity.

Determinism versus social construction of media technology

When historians consider how a technology is developed, there are often two basic schools of thought at work: determinism and social construction. Determinists see technologies as path-dependent, with inevitable changes and consequently predictable impacts on society. Social constructionists see a stronger influence for economics, politics, and culture that controls technological development. Neither is right or wrong, and both perspectives are often applied to the study of media technology.

Marshall McLuhan took this deterministic view when he said we need to anticipate the process of social change that communication technologies generate. But whether or not we anticipate the change, there will still be an impact. He said in a 1969 interview:

Because of today’s terrific speed-up of information moving, we have a chance to apprehend, predict and influence the environmental forces shaping us—and thus win back control of our own destinies. The new extensions of man and the environment they generate are the central manifestations of the evolutionary process, and yet we still cannot free ourselves of the delusion that it is how a medium is used that counts, rather than what it does to us and with us.

Technological determinism was probably best articulated by historian Charles Beard, who said, “Technology marches in seven-league boots from one ruthless, revolutionary conquest to another, tearing down old factories and industries, flinging up new processes with terrifying rapidity” (Beard 1927). It was simplified into the grim motto of the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair: “Science Finds, Industry Applies, Man Conforms.”

To a large extent, media technologies have been seen as less deterministic than (for example) technologies in energy or transportation. Still, it’s important to realize that many experts see unavoidable impacts in media technologies.

For example, fiber optics, satellites, and digital networks have “flattened” the world, according to New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman. They have made it just as easy to process information or do business in India as it is in Europe or North America, he notes in his 2005 book, The World is Flat. While social institutions might buffer some of the impacts, the global sharing of semi-skilled information work has brought the world closer but has also destabilized employment in banking, news, entertainment, and other areas.

For example, Eastman Kodak, the film and camera company, once employed 140,000 people, but went bankrupt in 2012 after widespread adoption of digital cameras. Where did all that economic value go, asks Jaron Lanier in a 2014 book, Who Owns the Future? Digital networks tend to centralize wealth and limit overall economic growth, enriching only a few in the process, he says.

According to Google founder Larry Page, the acceleration of digital technologies might eventually eliminate nine of out ten jobs, but may also make basic living costs much cheaper. “When we have computers that can do more and more jobs, it’s going to change how we think about work. There’s no way around that. You can’t wish it away” (Walters 2014). This is classic determinism, of course, since “wishing” is certainly not the only possible social constraint on technology.

The possibility that technology could accelerate to a point where no social process could exert any control whatsoever is considered to be a technological “singularity” beyond which any future is opaque. For example, futurist Raymond Kurzweil asks what would happen if the global network of computers acquired intelligence. That would be a “singularity,” because after that, no one could predict what might happen. The network could even make decisions about ending all human existence (Kurzweil 2005).

The counter-thesis to technological determinism is social construction of technology, which is the idea that social processes (including politics, economics, and culture) have more influence on the development of a technology or on its impacts than the technology’s own characteristics.

For example, in most countries during the early to mid-twentieth century, nearly all communication media—from post offices to telegraph companies, to telephone and radio television systems—were socially constructed through national and international telecommunications regulatory agencies, such as the International Telecommunications Union (part of the United Nations) and, on the national level, agencies like the US Federal Communications Commission. Only print media achieved a relatively high degree of freedom, through the First Amendment in the US and similar traditions in Europe and other countries.

The relatively negative experience with over-regulation of electronic media in the US during the mid-twentieth century had a strong influence on the way the world wide web was socially constructed in the 1990s, when innovators successfully argued that the Web should be relatively unregulated, like print media.

Another perspective on the social construction of technology is that inventors themselves tend to infuse their own values into technology. For example, Steve Jobs of Apple computers wanted to make personal computing possible and then tried to control it when he was successful; Thomas Edison also tried to retain control of the motion picture industry. Sometimes an inventor’s values come into conflict with powerful industrial or social forces. Brian Winston, for example, describes the emergence of some media technologies as influ- enced by what he calls the law of the suppression of radical potential (Winston 2008).

Similarly, values may also be infused in the broad inventive process as people come to believe that things could be done better. Historian Robert Friedel calls these “cultures of improvement,” as key technologies are “captured” and become part of a sustained series of changes. The jockeying for power surrounding these technologies is the process by which a technology is controlled (Friedel 2007).

So, is the medium is the message? Or, perhaps we should ask, to what extent is the medium the message? If the dark side of printing was empire, colonialism, capitalism, and the rise of the nation state, what was the dark side of electronic and digital commu- nication? Would the new technology just intensify the same trends? Or would it, as McLuhan believed in the 1960s, produce a qualitative change in society and cultural life, liberating users from the limitations of the past (Blondheim 2007)?

There’s no question that, in comparison to McLuhan’s era, we are seeing rapid, deep qualitative changes in the media and in society. Old media empires have disintegrated and new kinds of media functions are animating an emerging global culture. Rather suddenly in human history, we have instant language translation, free international encyclopedias, and free media exchanges in text, audio, and video between individuals and groups from anywhere in the world. None of these things were widely available before the 21st century. We also have unusual public encounters between very different cultures that have never much been in contact before, and as a result, conflicts over closely held values and an increasing drift towards international speech restrictions.

Utopians and Luddites

When people embrace technology in an extremely optimistic way, they are said to be technological utopians. For example, much of the rhetoric surrounding the development of the telegraph, the early years of radio, and the early years of the internet tended to be influenced by this sort of enthusiasm. The telegraph will make “one neighborhood of the whole country,” Samuel Morse wrote about 125 years before McLuhan’s idea of the “global village.” Similarly, H. G. Wells envisioned the morning television report as a staple of a utopian communal village of the future (Wells 1898).

When people reject technology in an extreme and pessimistic way, they are sometimes called Luddites. The term goes back to 1811, when thousands of British textile workers lost their jobs following the introduction of steam-powered machinery. Mobs of starving workers broke the textile machinery and blamed it on a mythical figure named Ned Ludd, who, according to legend, was a simple-minded boy who accidentally broke textile machinery. Apparently, the Luddites only intended to destroy property, but there were accident deaths of mill owners, and as a result, about two dozen were executed and more were exiled to Australia. French workers with a similar idea of resisting unfair working conditions by breaking machinery with wooden shoes (sabots) led to the term sabotage.

The Luddite movement was very much on the mind of London Times owner John Walter II when he promised workers that they would keep their jobs even after steam printing presses were introduced in 1814. Walter’s enlightened response didn’t work 150 years later, when printing technology triggered a wave of “new Luddite” labor disputes, including the very damaging four-month New York newspaper strike of 1962–3 (Kempton 1962).

Enthusiasm for new technologies has been more the rule than the exception, but skepticism about virtually every technology is not difficult to find in history. One of the chief critics of technology in the nineteenth century was Henry David Thoreau (1817−62), the transcendentalist writer and author of “Walden.” He was especially skeptical about the telegraph, which he considered merely “an improved means to an unimproved end.”

Another technological skeptic was writer and diplomat Henry Adams (1838−18). He worried that civilization had left behind an old world concerned with religion and had entered a new one, a world concerned with science and technology but morally and philo- sophically adrift. His point of comparison of the two ages of civilization was between the Virgin, a symbol of old Europe, and the Dynamo, a symbol of new Europe (Adams 1917). This idea has been often repeated in discussions about technology.

Fallacies and anachronisms

Sometimes predictions for technological directions that do not occur are called techno- logical fallacies. The fallacy that computers would lead to a police state is important to consider in the history of computing because, in the 1970s, it led to a preference for individual, non-networked personal computers.

It was also a partial fallacy for Alexander Graham Bell and other inventors of the late nineteenth century to predict that the telephone would be used more or less as a medium for music and news broadcasting, in the way that eventually occurred with radio in the 1920s. It was a complete fallacy for Guglielmo Marconi, inventor of the radio, to predict that radio waves could stimulate plants and act as a new kind of fertilizer. In the 1950s and 1960s, comic book detectives carried “wrist televisions” like wrist watches to communicate with each other—again, something of a partial fallacy, in that such devices are possible. Following the introduction of the Apple watch, which doubles as a cell phone and personal information assistant, we may now have the return of the comic book detective.

Envisioning the future has always been an interesting and sometimes productive pastime, but the future isn’t what it used to be, as many authors have noted. The atomic- powered airplane, the personal helicopter, the robot valet—all have been chalked up by now as technological fallacies (Barbrook 2007; Dregni 2006).

Anachronisms (which means “contrary to time”) often confuse two or more time periods. For instance, medieval paintings and Renaissance-era woodcuts often portray biblical figures with fashions or weapons typical of the era when the paintings or woodcuts were made.

Anachronisms (which means “contrary to time”) often confuse two or more time periods. For instance, medieval paintings and Renaissance-era woodcuts often portray biblical figures with fashions or weapons typical of the era when the paintings or woodcuts were made.

Interestingly, the usual portrait of Johannes Gutenberg is an anachronism, since it was created to illustrate a different person 100 years after Gutenberg’s death and totally misses the typical fashions and style of Gutenberg’s era in Mainz, Germany.