Louis Daguerre announced his practical method for taking photos in 1839. He believed the discovery was so important that he put the patent in the public domain.

Photography literally arrived overnight in the summer of 1839. One day sketches and paintings were the only way to preserve the appearance of the past. The next day, a Daguerrotype studio would be springing up in your city.

The Daguerrotype process was named for Louis Daguerre, a Parisian artist who had been trying to speed up the production of realistic paintings. In the 1820s and 30s, Daguerre worked on elaborate museum scenes called dioramas — a popular form of entertainment back then. His dioramas included reproductions of Chartres Cathedral, the Environs of Paris and famous battle scenes.

Daguerre became obsessed with finding a quicker way to accurately depict background landscapes by making automatic impressions of the cathedrals or battle scenes. At the time, certain chemicals were known to be sensitive to light, but it was only possible to get a temporary image. No one had been able to “fix” the image so that it would last. Daguerre and a fellow diorama painter , Joseph Nicephore Niepce, discovered found the secret. (Photohistory explains the details of the Daguerrotype process.)

Daguerre did not try to make a fortune with his process, nor did he attempt to control its use for profit or for a moral purpose, as later inventors would do with radio and movies. Instead, he disclosed the exact details of the process at an Aug. 19, 1839 meeting of the French Academy of Sciences. He gave his invention as a gift “free to the world” and within a matter of days and weeks, photographic studios sprang up in cities around the world.

Samuel Morse, inventor of the Morse Code for the telegraph, happened to be present in Paris when Daguerre’s process was announced. At the time, Morse was still struggling to find funding for the telegraph. Thinking that photography would sustain him for a time, he ordered a camera and gathered materials to take back to New York. By September of 1839, Samuel Morse was teaching the art of photography at NYU. One of his students, Mathew Brady, soon opened a studio on Broadway and later took thousands of photos of the American Civil War.

“I was introduced to Morse (in 1839), who was then painting portraits at starvation prices in the university rookery on Washington square,” Brady wrote. “He had just come home from Paris and had invented upon the ship his telegraphic alphabet of which his mind was so full that he could give but little attention to a remarkable discovery one Daguerre, a friend of his, had made in France” (Horan, 1955).

In 1844, Brady opened his portrait studio over a saloon on New York’s busiest street—Broadway. Not only did he offer daguerreotypes at a reasonable price, but he also sought advice from the best chemists to help refine his techniques. His portraits soon began taking first place in competitions, and by the late 1840s he was a household name: “Brady of Broadway.”

Brady also made a point of documenting the likenesses of the most famous people of the day for The Gallery of Illustrious Americans. His subjects were everyone still living who was important—Dolly Madison, Andrew Jackson, James Polk, and many other actors and politicians famous in their day

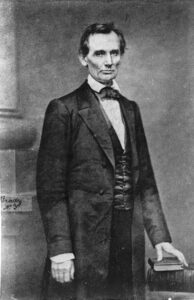

In 1860, when an Illinois politician gave an important speech in New York’s Cooper Union lecture hall, he also stopped by Brady’s of Broadway. The photo of Lincoln was reproduced by the thousands and became the best known image of the 1860 presidential campaign. “Brady and the Cooper Institute made me president of the United States,” Abraham Lincoln said (Horan, 1955).

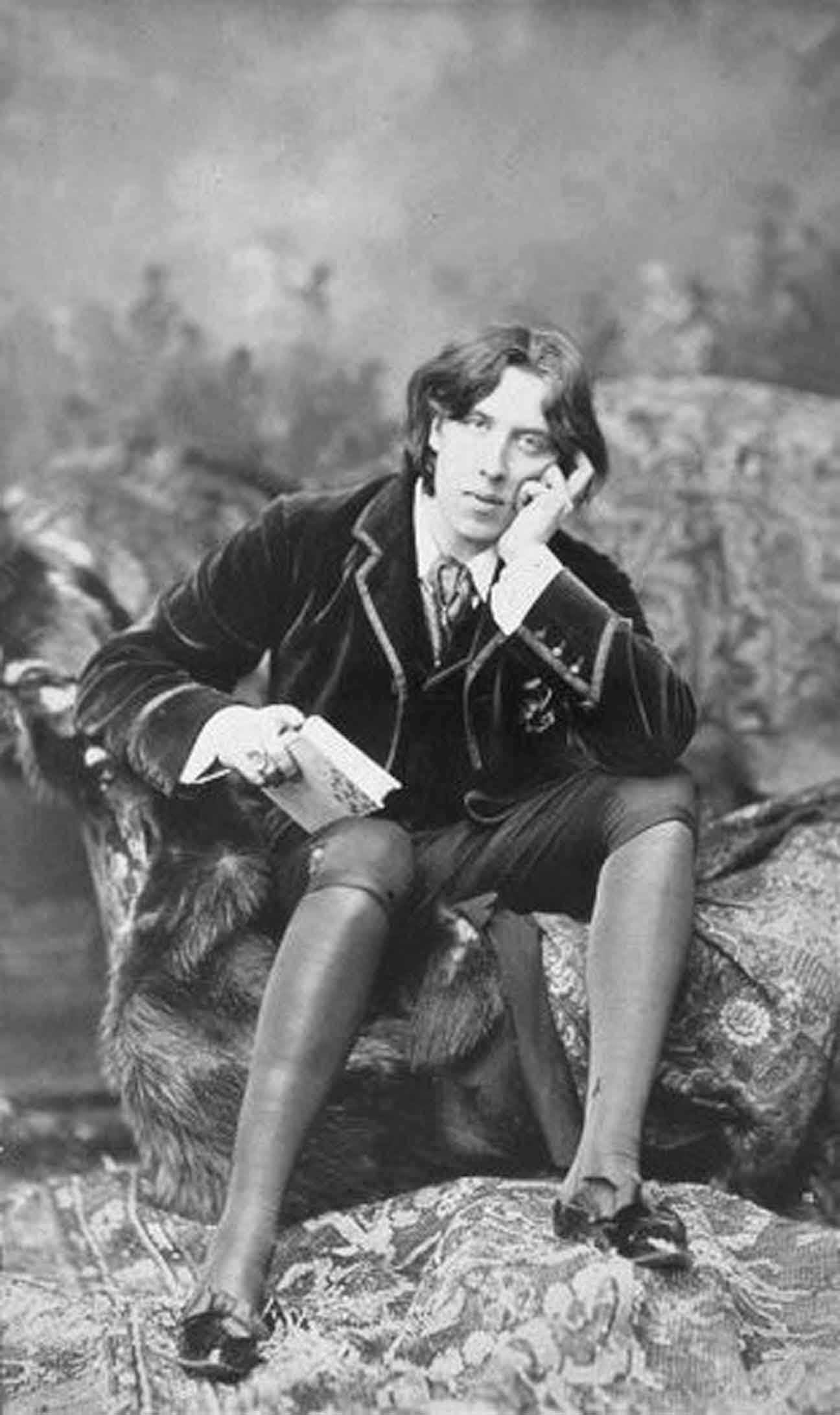

Oscar Wilde photo by Napoleon Sarony, 1882. Copyrights for this and other Sarony photos of Wilde were disputed in court because photography was “not an art.” The court said it was.

As photography became popular in the 1840s and 50s, the question of whether photography was art or simply some form of mechanical reproduction became important on an abstract cultural level and also for legal and economic reasons. A controversy erupted in the United States in the 1884 when a photograph of playwright Oscar Wilde by the New York photographer Napoleon Sarony was widely reproduced without permission by the Burrow-Giles Lithographic Co. Sarony (the photographer) sued the lithographic company, and the case went to the US Supreme Court. (Burrow-Giles v Sarony, 1884).

The debate over the legitimacy of photography raged on long after copyright cases were settled in France and the United States. A series of artistic movements and counter-movements inspired new approaches by new generations of photographers and artists.

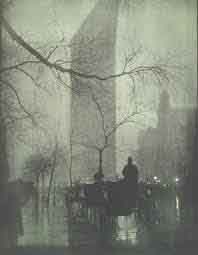

Edward Steichen’s Pictorialist image of New York’s Flat Iron Building (1905) proves that photography is really “art” (and deserves to be copyrighted).

Portrait painters still felt that photography was not legitimately artistic, and this spurred the “Pictorialist” photographic movement. In defense of their art, Pictorialists depicted subjects with soft visual effects and artistic poses. One part of the movement was the “The Brotherhood of the Linked Ring” founded in Britain in May, 1892. Similar clubs were formed in Vienna and Paris to promote the artistic side of photography. American Pictorialists included Alfred Stieglitz and Edward Steichen, who opened the 291 Gallery in New York. They were determined that photography would find its place “as a medium of individual expression,” as Steiglitz said. The gallery proved successful in selling fine art photography, taking the forefront of modern art in the pre-World War I period. Among the best known photos of the period is the Flat Iron Building, taken by Steichen.

The success of the 291 Gallery inspired another reaction in the Straight Photography movement. Photographers like Paul Strand thought pictorialism was too apologetic, and did not take advantage of the new medium. Strand took photography into advertising and abstract work with the idea of “absolute unqualified objectivity” rather than artistically manipulated photos.

Paul Strand’s Wall Street photo is meant to be an indictment of the system of isolated individuals and cold, domineering corporations.

Strand was politically liberal, and like other photographers of the era used the camera to advance social causes as well as present artistic subjects. The overbearing architecture and isolation of people in his 1915 Wall Street photo is a social comment as much as an artistic expression. Like many American artists, Strand suffered from blacklisting during the post-World War II reaction to communism, and spent the last three decades of his life in Europe.

On the US west coast, a group of photographers who sided with Strand’s Straight Photography movement formed the f/64 Group in the early 1930s. The name is a reaction to Stieglitz’ 291 but is also a technical description of an approach to photography. F/64 is a lens aperture setting that requires long exposures and intense lighting, resulting in strong, clear images with extraordinary depth of field. The modernistic approach to photography is also seen in attention to underlying geometrical patterns. Ansel Adams’ work is probably the best example. Other members of the group included Imogen Cunningham and Edward Weston.

Among the first to use flash photography in the United States was photojournalist Jacob Riis (1849–1914), who used it to take photos of squalid conditions, dangerous alleys and suffering children, Riis was also able to take advantage of another new media technology—the “halftone” process that screened a photograph into small dots that could be printed on paper.

In his 1890 book, “How the Other Half Lives,” Riis published a mix of photos and drawings about what he saw when he found roaming the streets of New York with his friend Theodore Roosevelt, who was then commissioner of police. He wrote about the rising death rate from disease and lack of sanitation. Theodore Roosevelt said: “The countless evils which lurk in the dark corners of our civic institutions, which stalk abroad in the slums, and have their permanent abode in the crowded tenement houses, have met in Mr. Riis the most formidable opponent ever encountered by them in New York City.”

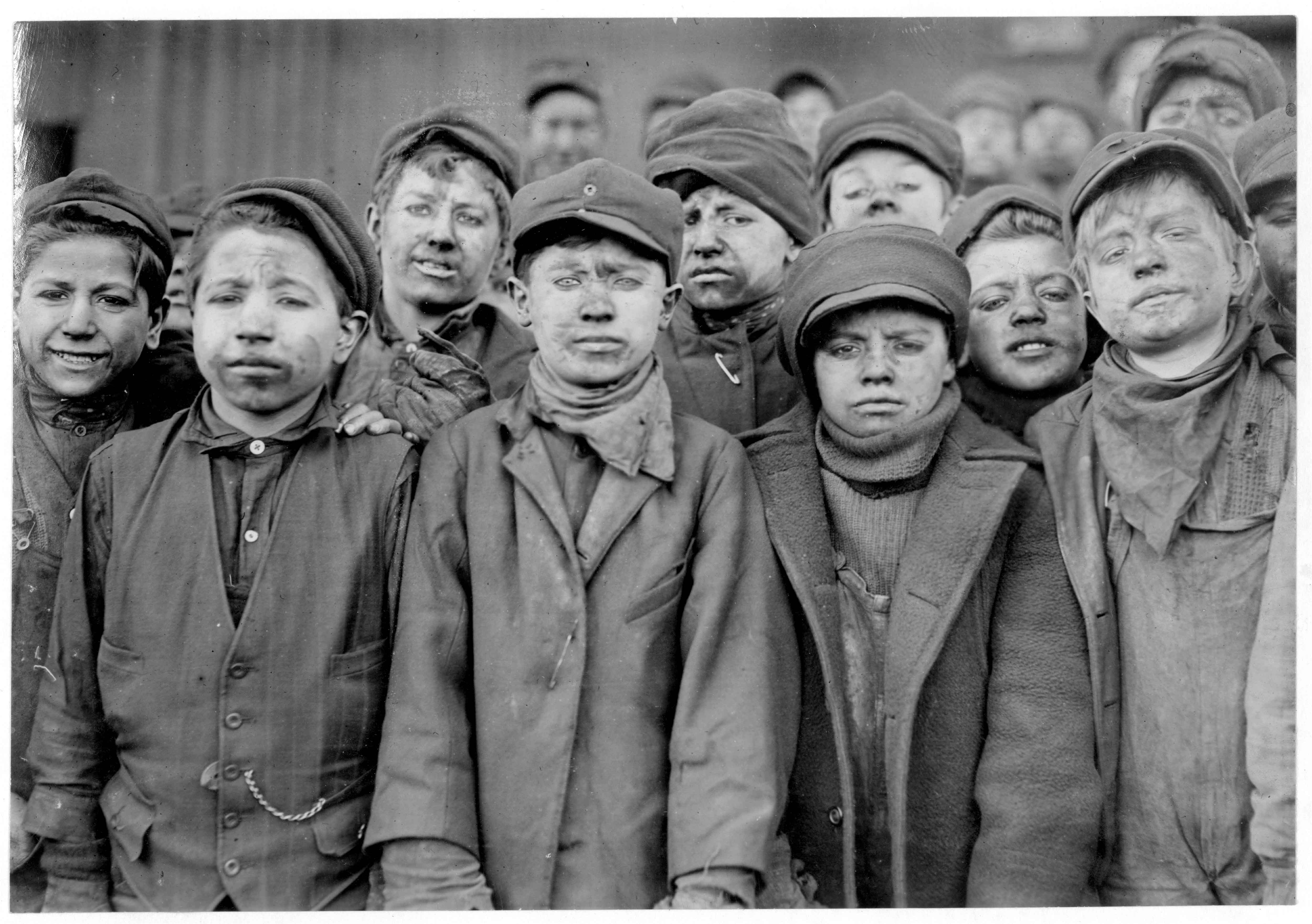

Another example of photography for social reform involved Lewis Hine (1874–1940), a photographer who joined the National Child Labor Committee in 1907. Hine’s stunning portraits of children working with dangerous machinery proved to be more powerful arguments than anything that could be said or written. By 1916, child labor reform laws had been enacted.

Another example of photography for social reform involved Lewis Hine (1874–1940), a photographer who joined the National Child Labor Committee in 1907. Hine’s stunning portraits of children working with dangerous machinery proved to be more powerful arguments than anything that could be said or written. By 1916, child labor reform laws had been enacted.