Setting type for a newsletter in Altmärkische Wische, Germany, September, 1958. (German Federal Archive)

The bridge between the ancient world and the modern era was built by the printing press. This is hardly an exaggeration. Printing played a central role in revolutionizing the world, beginning with early modern Europe. The question is why?

The goal in these exercises is to try out the different techniques and consider their immediate advantages and disadvantages. Here we’ll set type by hand and consider the “monk power” of a printing press.

Theory: Consider Elizabeth Eisenstein‘s history of the printing press as an agent of social change.

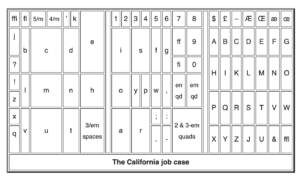

Video: How to set type Reference: California Job Case type compartments

Materials: Printing equipment can be expensive. One way to stage a hands-on experience is to invite nearby artists and crafts printers to come to your class. Woodcuts or potato prints can also give a feel for the history of printing technology. If you’re buying antiq ue printing equipment, two of the best places to look are on Ebay and Facebook.

ue printing equipment, two of the best places to look are on Ebay and Facebook.

Life in a print shop: The culture of printing.

Handout: ThePrintingRevolution

The Printing Revolution

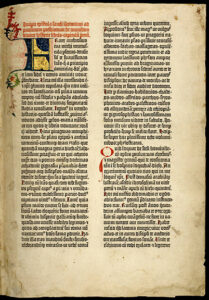

People were astonished when they saw the first unbound pages of Johannes Gutenberg’s Bible at Frankfurt’s traditional harvest fair in 1454. There were none of the blemishes, rubricator’s marks, or scraped-out ink spots that characterized hand-lettered manuscript Bibles. The linen paper was bright, the edge of the type was crisp, and, at 30 florins, the cost was one-tenth of a manuscript Bible.

“The script was very neat and legible, not at all difficult to follow,” wrote an enthusiastic bishop to his supervisor. “Your grace would be able to read it without effort, and indeed, without glasses.” He also called Gutenberg a “marvelous man,” which is one of the few personal insights we have into the life of Johannes Gensfleisch zur Laden zum Gutenberg (Eisenstein 1980; Fussel 2005).

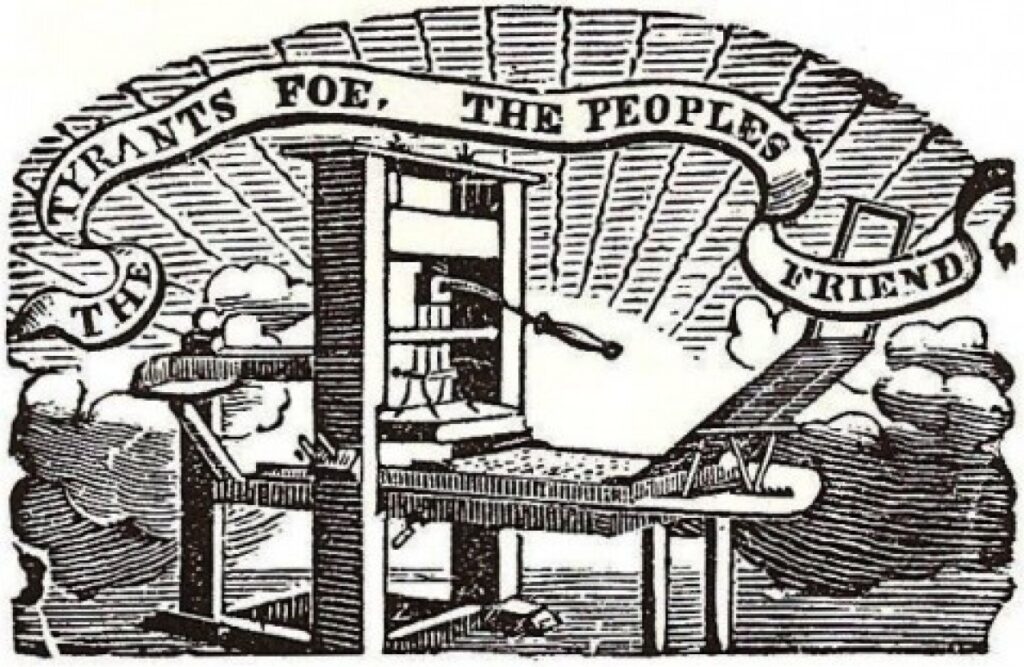

Why is this moment so important in history? First, printing accelerated the distribution of knowledge just at the height of the Renaissance. The Bible and other religious manuscripts were increasingly available, and not just in Latin, but also in vernacular languages (German, French, English, etc). Secondly, with increasing book production came increasing literacy and a growing willingness and ability to question authority. This led to the Protestant Reformation and an upheaval in European culture. It is considered the major turning point in Western civilization.

Moveable metal type was the key technological breakthrough. The press was already well known, there was lots of paper and parchment around, and moveable type made from wood was being used in the Netherlands in the 1450s. But wood does not hold up for more than a few thousand impressions, and it can’t be re-used. Gutenberg solved the key problem.

Who was Johannes Gutenberg? We know that Gutenberg was born around 1398 in Mainz, Germany, at a time of plague, social chaos, and political upheaval. We think that his father was a cloth merchant and a goldsmith for the Church, and Johannes may well have learned that craft. We have a record of his enrollment at a university around 1418. We know of a will that mentions him in 1419, and there are records of a disputed promise of marriage in 1436. That’s about all we know about his early life, except that he ran into problems with an intriguing business in 1439.

Pilgrim’s Badge— a small metal medallion worn by people on religious pilgrimages during the medieval and Renaissance periods. This badge is from the Aachen pilgrimage.

Gutenberg’s business involved a new way to make the small metal badges that were popular with people who were on religious pilgrimages. The badges, or “pilgrims’ mirrors,” were four inches high and made from cheap metals such as lead and tin. They would be sewn onto hats or cloaks to show that the traveler was a pilgrim, and they would be held up in the presence of religious relics as the pilgrim’s act of devotion. Millions of the badges were sold across Europe between the medieval era and the late Renaissance. Even today, the badges are still being dug up along the old pilgrim trails.

From court records, we know that two investors backed Gutenberg in an improved process for making the metal badges. They expected to sell 32,000 of them, and they were well into production when news came that the Aachen, Germany, pilgrimage was being postponed due to bubonic plague. With the setback, Gutenberg realized he needed another way to keep investors happy.

Johannes Gutenberg—This is the traditional but probably incorrect likeness of the printer from Mainz. The hat and beard would not have been worn by someone from his time and culture. However, no better images exist, according to the Gutenberg Museum in Mainz, Germany. (John Luther Ringwalt, American Encyclopedia of Printing, Menamin & Ringwalt,1871.)

When Gutenberg started his second enterprise in Strasbourg, he used the same alloy of lead, tin, and antimony that he used in making pilgrim’s badges. Gutenberg continued to experiment with metal type and presses during 1440s, and he may have printed several undated works such as a Latin grammar and an astronomical calendar in that time.

After a few years, he returned to Mainz to assemble a printing system that would produce the flawless 1,282-page, 42-line Gutenberg Bible. This complex system included metal forges and molds for type; a way to set the type; a long-lasting ink; a new kind of press; contracts for high quality linen paper; methods to stack and order pages; and financing to pull the system together. Sales of the new Bibles were not slow, but in 1456, just as the printing company began to look like a financial success, Gutenberg’s investor Johann Fust (or Faust) foreclosed on the loan and took over the business. Gutenberg probably continued in another small printing operation in Bamberg, and then worked for the Church in other ways in Mainz. He died in 1468.

Meanwhile, Fust and his son-in-law, and former Gutenberg foreman, Peter Schoffer, began the second wave of the printing revolution with a popular form of religious book called a psalter. They also printed two editions of works by the Roman poet Cicero and a “Letter to the Imperial Estates” describing the issues in a war between two contending bishops in Mainz in 1462. It was one of the first uses of the press to disseminate and comment on the news of the day.

For almost a decade, the printing industry grew slowly and stabilized in central Germany as several dozen people trained in the craft. Then in 1465, two German printers sponsored by a Catholic cardinal started a new printing operation near Rome. By 1469, three other German printing companies had moved to Venice, and by 1471, the number of printing businesses began a dramatic growth. By 1480, every city in Europe had at least one printing company.

Precursors of the printing revolution

Gutenberg’s system of printing text with moveable type was new in 1454, but the process of making an impression with ink on a raised surface was ancient. The earliest known printed images are from “cylinder seals” used in early Mesopotamian civilizations from around 3500 bce. Made from hard stone, glass, or ceramic materials, they were rolled across wet clay or textiles to create repeating patterns. Engraved seals and stamps continued to be used for thousands of years to print on clay and cloth. Chinese artists and scribes used woodblock printing for images, and sometimes text, starting from the sixth century ce. In Europe, similar woodblock images were widely used for playing cards and pictures of saints from the 1200s on. Artists who wanted fine detail and longer press runs shifted to metal plates by the 1400s.

Still, the transition from engraving and woodcuts to printing with moveable type was not easy to make. Woodblock printing is not suitable for more than a few thousand impressions since images and text start to get fuzzy as the edges of the wood break down under the pressure of the press. Engraving plates are one way around the problem, since text can be engraved on a copper or zinc plate, but they are expensive and difficult to correct. When thousands of impressions are needed for individual letters, something stronger and more flexible than wood is required.

Bi Sheng, Gutenberg Museum, Mainz, Germany. Letterpress printing in Chinese requires many thousands of characters.

Chinese scholar Bi Sheng (906−1126 CE) was the first to come up with a solution to the moveable type problem. Between 1041 and 1048 during the Song dynasty, Bi Sheng cut characters onto the top of thin clay squares, and then baked them into hard ceramic tiles. The difficulty was in keeping the surface height of all of the separate tiles exactly even in order to ensure that the ink would be perfectly distributed. Even one millimeter can mean the difference between a good impression and one that is too light to read. Bi Sheng’s solution was to place all the tiles on a board with a thick coat of wax, and then heated up the board. When the wax was soft, he pressed the tiles down from the top with a metal plate, making them all even as they receded into the wax. Then he would let the wax cool.

The idea worked, but there was a larger problem: Chinese language is logographic, with many different symbols required. This is no obstacle for hand-painted text, but a moveable type system required at least 6,000 tiles. So the complexity of a logographic language made it difficult to sort, set, and use moveable type. On the other hand, the Western Latin and Cyrillic alphabets require only about 150 characters. So even though the hardware problem was solved in China, the larger software problem remained, and it was almost as easy to cut woodblocks as it was to set type with a 6,000-character system.

A similar moveable type system was developed in Korea in 1377 using brass characters and woodblock printing, but, Korean, like Chinese, is logographic. While the process worked, it was not a way to drastically cut the cost of communication (Schramm 1989).

A Dutch printer named Laurence Coster (1370–1440) came close to solving Europe’s printing problem. The story is that he was playing blocks on the floor with his children when he had the idea to separate parts of the wooden block. The individual wooden characters could then be replaced when they started to wear down. Coster was apparently in the process of switching to metal characters when he died in 1440 (Sonn 2006).

These are just a few of the many rival claims to the legacy of moveable type printing, and the question is often asked whether Gutenberg is in fact the inventor of the technique. From the records and testimony that we have, it does seem clear that Gutenberg was first to solve the key problem of metal type and assemble all the necessary ingredients to create the printing revolution (Taylor 1907; De Vinne 1878; McGrath 2001).

Even so, the printing revolution did not occur because one lone genius invented a single new technology. Printing emerged because Gutenberg’s insight into the key problem of moveable metal type occurred at a moment when all of the right conditions and technologies were in place. These included a surplus of paper and ink, as well as presses for printing, foundries for metal smithing, and a system for business investments.

Most importantly, it occurred because of the rising need for education among the nobility and merchants of Renaissance Europe starting around the 1200s. The purchasing power of the new readership expanded the market to the point where scribes and illuminators were not keeping up with demand.

The printing revolution took place because of “a complex ensemble of many inter- related changes” in social conditions, said historian Elizabeth Eisenstein. “Gutenberg invented moveable type,” said historian John Lienhard. “But, it’s no exaggeration to say that Medieval Europe worked for 300 years to invent Gutenberg” (Lienhard 1992).

Diffusion of printing in Europe

Mainz, Germany, was the birthplace of printing; but Venice, Italy, was its cradle. As the most powerful and cultured city in Europe, Venice naturally attracted half of Europe’s printing trade during the High Renaissance. By around 1500, Venice had over sixty-five publishing businesses with 200 presses and thousands of people working in printing, paper making, and type foundries.

Two German printers, John of Speyer and his brother Wendelin, were the first to bring printing to Venice in the late 1460s. They produced at least 800 copies of four books— three Roman classics and a book by St. Augustine—in a seven-month period between 1469 and 1470 (Brown 1891). The output of the new printing presses was remarkable for the time; one monk in a monastery might, in that same seven months, have produced only part of one book.

Nicholas Jenson (1420–1480), of Champagne, France, was another printing pioneer in Venice. Jenson’s previous job as an engraver at a government coin minting plant in France made him uniquely qualified for the printing trade, since he could design and cut type faces on the metal punches used in type foundries. Jensen had been in Mainz to study under Gutenberg and his successors, and left for Venice in 1468. There he invented “roman” type, which was based on the capital lettering used in Roman architecture, along with a standard lower-case script style developed by monks between 800 and 1200 ce. Roman was more legible than Gutenberg’s blackletter (gothic) style, and was quickly adopted as a standard.

Jensen, the Speyers, and other early Venetian printers catered to an elite readership, and they tended to see books as works of art in themselves. They printed the books in small editions on high quality parchment with elaborately illuminated initials at chapter heads and handsomely tooled leather bindings.

Aldus Manutius (1449–1515) changed the high-end business model in the 1490s when he began publishing books for the public at reasonable prices, rather than as works of art for the elite. Between 1494 and 1515, his company produced 157 different books, some with more than 1,000 copies. “While Jenson and his fellows looked upon the press largely as a means for putting out a handsome book [as] a beautiful work of art,” said historian Horatio Brown, “Aldus regarded it quite as much as an instrument for the diffusion of scholarship” (Brown 1902).

By 1500, Venice had produced half of the four million first printed books, called “incunabula” (Latin for cradle). But other cities were catching up. By 1500, Paris had seventy-five printing houses and was beginning to surpass Venice, thanks in part to strong royal patronage. By 1533, another 18 million more books were produced by Europe’s rapidly expanding publishing industry (Smiles 1867).

Today, only a single plaque on a wall near the Rialto bridge marks the city’s once bustling printing center, noting, “From this place spread the new light of civil wisdom.” But as Venice declined in power and freedom, the industry moved north to the great printing centers of Amsterdam, Brussels, Frankfurt, Paris, and London.