DROFDAR — Governor’s School students read a dramatic script from their cell phones under a studio microphone. The students are acting out “Drofdar” — a fictional script about a missing student from an imaginary prep school. Note the overhead microphone and the foley (sound effects) box on the table.

The script was written over a two-week period following prompts from the instructor with background from Aristotle’s poetics, Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s journey and Jon Franklin’s Writing for story. We also reviewed scripts from the Golden Age of radio; some of these are listed below.

One collaborative technique we used was to cover a table with perhaps eight linear feet of thick white paper and a bouquet of multicolored pens and pencils. The students greatly preferred paper on the table, rather than on a wall, since everyone around the table could could contribute to the plot.

We used Audacity rather than the lab computers. Audacity is a free application, so students could download it to their own laptops and work outside of classroom time.

Drofdar was performed to wild applause on the final day of Governor’s School — the “showcase” day where activities were shared with other students. Along with the performance, media history students also enjoyed sharing sound effects techniques with other students.

Training, acting and editing tips

- Voice training & podcasting tips

- Audio recording

- Audio formats

- Audio editing

Radio news resources

Historical resources

- Journalism history on the air — This is a surprisingly extensive collection of radio programs from the 1930s – 50s with journalists as protagonists. Most are fiction but some programs are recreations of real events. Curated by journalism historian Bob Stepno, PhD.

- Script library for old-time radio.

- Heroes and villains from the Golden Age of Radio

- List of old time radio programs (more scripts below)

Radio history

From Revolutions in Communication Chapter 7

The mysterious forces surrounding electric currents fascinated scientists of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries—from Luigi Galvani and Alessandro Volta in Italy to Benjamin Franklin in America and Michael Faraday in Britain. When telegraph lines began stretching across continents, the mystery deepened as scientists tried to explain occasional fluctuations in electrical current that seemed to be associated with the Aurora Borealis and solar flares.

Particularly mysterious were the events of September 2, 1859, when the sky filled with auroras of writhing purple and red colors unlike anything ever seen before. “Around the world, telegraph systems crashed, machines burst into flames, and electric shocks rendered operators unconscious,” said historian Stuart Clark.

We now know that the worldwide auroras of 1859 were the same as the “northern lights” usually seen in polar regions, and that the auroras expanded for a few days due to a giant solar flare. We also know that electromagnetic fields travel invisibly through the atmosphere. And we call the solar storm a “Carrngton event” for the English astronomer, Richard C. Carrington, who observed the solar flare and described it at the time.

Like Discovering a New Continent

Scientists wondered how electricity could be related to magnetism, and how the great auroras of 1859 could create electricity in telegraph wires. One piece of the puzzle was solved a few years later, when James Clerk Maxwell, a British mathematician, published a paper describing the electric and magnetic forces that could be carried through space without wires. Maxwell called it “displacement current.” Another part of the puzzle involved Thomas Edison’s observations about the behavior of one electrical circuit when it was near a similar circuit. The phenomenon, when one circuit mimics another without actually touching it, was called the “Edison effect.”

In the 1880s, Heinrich Hertz, a German scientist, found a way to test Maxwell’s theory by generating electromagnetic waves, detecting them, and measuring their velocity. When he published his findings in 1888, Hertz thought he had simply verified an interesting scientific speculation (Aitken 1992). “This is just an experiment that proves Maestro [teacher] Maxwell was right,” he said. “We just have these mysterious electromagnetic waves that we cannot see with the naked eye. But they are there.” Asked about the value of the experiment, Hertz told students: “It’s of no use whatsoever.” If Hertz saw no practical value in radio telegraphy, others were racing to lay claim to what seemed like a new continent that was just being discovered. In the United States, Nikola Tesla began giving demonstrations of short-range wireless telegraphy in 1891. In Britain, Oliver Lodge transmitted radio signals at a meeting of a British scientific society at Oxford University in 1894. Similar experiments were being conducted by Jagadish Chandra Bose in India at the same time. Radio experiments are also recorded in Germany, Russia, and Brazil. All faced the same problem: usually the signals would not travel more than a few dozen meters.

Guglielmo Marconi

An unlikely inventor is often credited with making radio telegraphy practical. Guglielmo Marconi, a twenty-year-old from a wealthy Irish-Italian family with little formal education, had become fascinated with electronic waves while attending a friend’s scientific lectures at the University of Bologna. In 1894, Marconi was able to duplicate Hertz’ experiments in his home laboratory, but he faced the familiar problem: he was not able to receive a signal over any great distance. At the time, most research was focused on the higher-frequency part of the radio spectrum, and physicists hoped to understand the relationship between radio waves and light waves.

Marconi moved down the spectrum, using lower-frequency waves. He also used high-powered transmitters and larger, grounded antennas. Marconi was not the first to think of using what we now call a “ground,” but he was the first to use it specifically for radio signaling, and he was also the first to fully describe the commercial potential of long-distance signaling. He arrived at just the right time, with the right financial and political backing connected with his family’s Jamison Irish whiskey fortune.

In 1896, Marconi was introduced to officials in the British Postal Service who, just that year, were finalizing the purchase of the last remaining commercial British telegraph company. This was being done to avoid the information bottlenecks created by monopoly systems like Western Union in the United States. Having nationalized the telegraph system by merging it with the Post Office, postal officials now saw a duty to fully investigate what they saw as an entirely new communications system.

In 1897, on a windy day on Salisbury Plain, near the ancient Stonehenge monument, Marconi showed government officials a practical radio telegraph system that could send a signal for 6 kilometers (3.7 miles). Over the next few years, the range of Marconi wireless systems expanded with higher-power amplifiers, and their value became obvious when radio helped rescue ships’ crews in distress off the English coast. As radio began saving lives and money, insurance companies like Lloyds of London ordered ships to install the new devices. By 1900, the Marconi radio telegraph could be found on most large ocean-going vessels. In several cases, Marconi operators saved the lives of many passengers. For example, in 1910, an operator named Jack Binns became famous for using radio to save passengers on the HMS Republic—a sister ship of the ill-fated Titanic.

Radio and the Titanic

Problems with radio played a major role in the Titanic disaster of April 14, 1912, when the British passenger liner sank after hitting an iceberg in the mid-Atlantic. These problems delayed and complicated the rescue, contributing to the deaths of 1,514 passengers and crew, and very nearly sealing the fates of those who managed to survive. Although its owners boasted that the Titanic was the most modern ship of its day, the Marconi radio system that had been installed in the weeks before the disaster was already obsolete. It was not, as was claimed at the time, the best radio technology available. Instead, the system devised by Guglielmo Marconi in 1897, and still in use in 1912, had long since been superseded by other radio pioneers—Reginald Fessenden and Lee DeForest in the US, and others in Europe. Still, Marconi used his patents, research, and monopoly power to hold back competition from other systems. And in the end, even Marconi himself admitted he was wrong to do so.

The Titanic was on its first voyage from Britain to the United States, and had just crossed the point where messages from ships at sea could be exchanged from the easternmost North American wireless station at Cape Race, Newfoundland. After sending personal messages from the Titanic, the operators were taking down news and stock reports for the passengers to read the next morning.

Just minutes before the Titanic hit the iceberg, Cyril F. Evans, a wireless operator on the Californian, which was about 20 miles away, attempted to contact the Titanic to tell them they were surrounded by dangerous icebergs. The captain of the Californian told Evans: “Better advise [the Titanic] we are surrounded by ice and stopped. So I went to my cabin, and at 9:05 p.m. New York time I called him up. I said, ‘Say, old man, we are stopped and surrounded by ice.’ He turned around and said ‘shut up, shut up, I am busy; I am working Cape Race’ [Newfoundland] and at that I jammed him.” When questioned, Evans explained to a US Senate inquiry: “By jamming we mean when somebody is sending a message to somebody else and you start to send at the same time, you jam him. He does not get his message. I was stronger than Cape Race. Therefore my signals came in with a bang, and he could read me and he could not read Cape Race.” “At 11:35 I put the [ear] phones down and took off my clothes and turned in.”

He was awakened by the Californian’s captain at 3:40 am when the crew observed distress rockets coming from the Titanic’s position. By that time, it was too late to help. Members of a British commission of inquiry were incredulous. “Do I understand rightly then that a Marconi operator … can only clearly hear one thing at a time?” one asked. It was, unfortunately true, and as the New York Times said a few weeks later, “Sixteen hundred lives were lost that might have been saved if the wireless communication had been what it should have been” (New York Times, May 2, 1912).

The official cause of the disaster was the negligence of the Titanic’s captain in ignoring iceberg reports. However, the delayed rescue effort was also a crucial issue, a US Senate committee found: “Had the wireless operator of the Californian remained a few minutes longer at his post … that ship might have had the proud distinction of rescuing the lives of the passengers and crew of the Titanic” (New York Times, May 29, 1912).

The Golden Age of Radio

Ten years and a world war after the Titanic disaster, the American Marconi corporation had become the Radio Corporation of America, and it was looking for programming that would attract an audience. RCA created the NBC network, and it began by taking a high-minded approach to public service. The programming schedule included lessons in music appreciation, productions of Shakespeare, political debates, and symphonies. By 1928, even as the network made its first profits from advertising sales, the “high-brow” symphonic and theatrical productions were drawing only modestly sized audiences

In fact, people were far more interested in popular entertainment. Vaudeville, the variety entertainment genre of theater, became the model for many local and national radio programs, and provided a platform for comedians, musical variety, and short dramas. Children’s and family-oriented programs were also especially popular, and these included Western dramas and comic-book heroes.

The public, anxious to escape the grim realities of the Depression, bought radios by the millions. NBC and CBS worked hard to keep up with the demand for programming. One of the favorite and best-remembered radio dramas of the 1930s was The Shadow, a melodrama concerning a crime-fighter with psychic powers. Its opening line, delivered with manic and sinister laughter, was, “What evil lurks in the hearts of men? Who knows? The Shadow knows.” Apparently the FCC knew as well.

The FCC objected when a Minneapolis, Minnesota, radio station allowed “certain words” (damn and hell) to go on the air when they broadcast Eugene O’Neill’s play Beyond the Horizon. And other controversial radio comedies. And they were especially outraged by a December 12, 1937 skit featuring Mae West and Don Ameche in the Garden of Eden. West says she is bored with life in the Garden and encouraged Adam to “break the lease.” At one point Adam asked what’s wrong with life in the Garden. Eve says: “You don’t know a thing about women… A couple of months of peace and security and a woman is bored all the way down to the bottom of her marriage certificate.” Adam responds: “What do you want, trouble?” And Eve says: “Listen, if trouble means something that makes you catch your breath, if trouble means something that makes your blood run through you veins like seltzer water, mmmm, Adam, my man, give me trouble.”

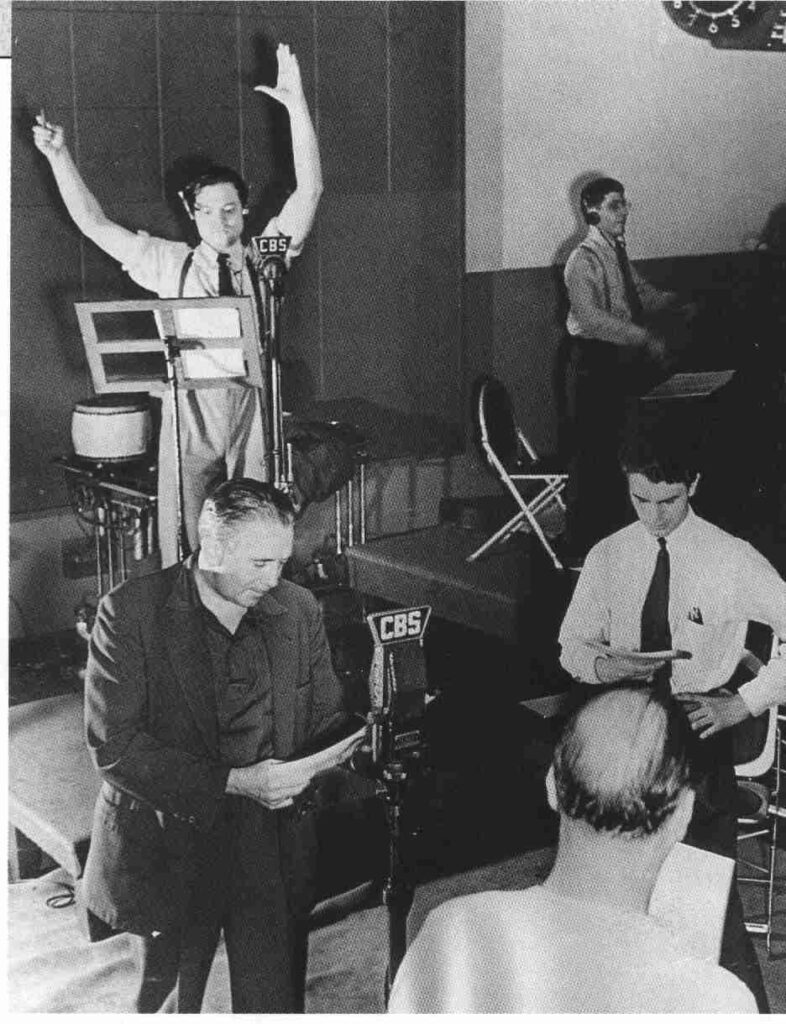

Orson Wells directing the Mercury Theater in 1938.

Another difficult moment during the Golden Age of Radio was Orson Wells’ “War of the Worlds” radio drama. The whole thing began as a Halloween prank. Welles had been hired by CBS to present non-commercial dramas such as adaptations of Treasure Island, Dracula, The Count of Monte Cristo, and Huckleberry Finn. CBS management hoped the productions, which had no sponsorship and no advertising, would help ward off FCC concerns about over-commercialization. Welles and the under-funded Mercury Theater were always under tremendous pressure to present these Sunday night programs, and when the idea for an adaptation of H. G. Wells’s War of the Worlds came up, Welles and others worried that it would be their least successful program to date. They decided to frame the narrative inside a series of newscasts to make it seem a little more realistic. John Houseman later recalled that the scriptwriters for the War of the Worlds did not believe the show would be quite up to standard. They studied Herbert Morrison’s Hindenburg disaster reporting as they rewrote it so that they could achieve the live news effect. “We all felt its only chance of coming off lay in emphasizing its newscast style—its simultaneous, eyewitness quality,” Houseman said. The show aired on October 31, 1938. Over the course of an hour, the Martian invaders traveled from their home planet, landed in New Jersey, released clouds of lethal gas and then took over New York. In the end, of course, the Martians were defeated by the humblest of earth’s creatures, the bacteria. All within an hour.

Listeners panicked as they heard what seemed to be a news broadcast about an invasion. Without interruptions for commercial sponsors, station identification, or even any warning that it was all just in fun, hundreds of thousands of listeners took to the streets, especially in New Jersey, as they attempted to flee the approaching Martians. Although no deaths or major incidents were reported, reaction to the prank was fairly strong. Within a month, some 12,500 newspaper articles were written about the broadcast (Hand 2006). Houseman attributed the press reaction to its disdain for radio itself. “Having had to bow to radio as a news source during the Munich crisis, the press was now only too eager to expose the perilous irresponsibilities of the new medium” (Houseman 1948).

Interesting contemporary podcast radio:

Decoder Ring Theater (Toronto) esp. Black Jack Justice

Project Audion – Modern OTR performances thru internet

Firesign Theater’s “Nick Danger – Third Eye” (a send-up of the noir detective) and The Giant Rat of Sumatra (a comedy about an unwritten Sherlock Holmes episode).

Wireless Theater Company (London ) – Oliver Twist, excellent audio production

More historical sites

Video: Radio and TV, Burton Holmes, 1940 https://archive.org/details/6111_Radio_and_Television_00_13_13_01

Transistor with radio tube history https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V9xUQWo4vN0

http://earlyradiohistory.us/ Huge site.

Golden Age Radio Programs & SCRIPTS

Lone Ranger origin story — Radio program and Script

More Lone Ranger scripts

Green Hornet

Justice Wears A Blindfold – Ep 350 – Aired 6-15-39 –

Script: Justice Wears a Blindfold

“The Ghost Who Talked Too Much”

https://youtu.be/OSDt3BivBr8

https://www.genericradio.com/s

Justice Wears a Blindfold:

https://youtu.be/egjemaH_y2Y

https://www.genericradio.com/s

The Corpse that Wasn’t There:

https://youtu.be/nNrc1TUMgAs

https://www.genericradio.com/s

Five Minute Mysteries – My Pal Patsy (Episode 1, 1947)

Script for My Pal Patsy and other Five Minute Mysteries

Script for Mr. Deeds Feb. 11, 1940. 58 minutes.

Campbell Playhouse Rebecca Dec. 9, 1938

Script for Rebecca with interesting introduction of Wells and explanation of the War of the Worlds broadcast the previous month.

Buck Rogers in the 25th Century Episode 1, April 5, 1939

Script for Episode 1

Dick Tracy and the case of the Big Top Murders 30 minutes

Script for Dick Tracy and the case of the Big Top Murders, April 6, 1946

Sam Spade, and the Dead Duck Caper, Episode 4

Script for Sam Spade, #4, Feb 2, 1947, 24 minutes

Superman, and Dr. Dahlgren’s atomic beam machine, #7, Feb 26, 1940

Script for #7 (Can’t locate continuing #8 )

The Big Story – The Bobby-Sox Kid from Bayonne [Dorothy Kilgallen]

The Big Story – The Bobby-Sox Kid from Bayonne [Dorothy Kilgallen]