Third edition 2025

Third edition 2025

The printing press, the linotype machine, the internet and the cell phone are shown in abstract here as elements of the great communications revolutions of our times. This edition was inspired by two profound thoughts by Francis Bacon and by US President John F. Kennedy:

“We should notice the force, effect, and consequences of inventions, which are nowhere more conspicuous than in those three which were unknown to the ancients; namely, printing, gunpowder, and the compass. For these three have changed the appearance and state of the whole world; first in literature, then in warfare, and lastly in navigation: and innumerable changes have been thence derived, so that no empire, sect, or star, appears to have exercised a greater power and influence on human affairs than these mechanical discoveries.” —Francis Bacon, Novum Organum, 1620

“It was early in the Seventeenth Century that Francis Bacon remarked on three recent inventions already transforming the world: the compass, gunpowder, and the printing press. Now the links between the nations first forged by the compass have made us all citizens of the world, the hopes and threats of one becoming the hopes and threats of us all. In that one world’s efforts to live together, the evolution of gunpowder to its ultimate limit has warned mankind of the terrible consequences of failure. And so it is to the printing press — to the recorder of man’s deeds, the keeper of his conscience, the courier of his news — that we look for strength and assistance, confident that with your help man will be what he was born to be: free and independent.” — US President John F. Kennedy, address to the American Newspaper Publishers’ Association, April 20, 1961

Second edition 2015

That’s a young Ben Franklin with his printing press in the upper left hand corner. Center left is the famous “Migrant Mother” photo taken by Dorothea Lange in 1936. To the right, slightly higher, is CBS news anchor Walter Cronkite describing the revolutionary potential of the personal computer in 1967. Below the title is a generic photo of a television camera and Ernie Pyle, the soldier’s writer of World War II, sitting down to at a typewriter, taken in Italy in 1943. And at the bottom, next to the broadcast antennae, are demonstrators at the memorial for the Charlie Hebdo victims of January 2015 in Paris.

First Edition 2011

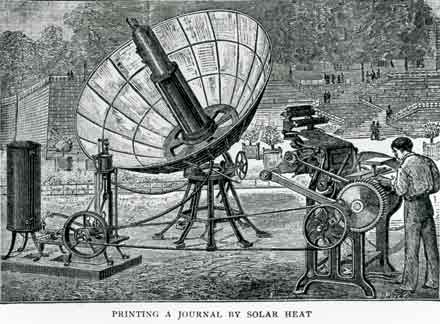

It looks like a giant satellite dish and a steam-punk computer, but it is really a solar collector running a printing press, developed by Able Pifre and displayed in Paris in 1883. What’s so interesting about the image is that it exemplifies a novel use of media technology to promote a new idea. New media technologies often come to the fore in revolutionary times because it’s easier for new ideas to get a hearing. This process of technological circumvention for the sake of social construction, rather than as part of a pre-determined technological trajectory, is one of the larger issues that need to be addressed in media history.

It looks like a giant satellite dish and a steam-punk computer, but it is really a solar collector running a printing press, developed by Able Pifre and displayed in Paris in 1883. What’s so interesting about the image is that it exemplifies a novel use of media technology to promote a new idea. New media technologies often come to the fore in revolutionary times because it’s easier for new ideas to get a hearing. This process of technological circumvention for the sake of social construction, rather than as part of a pre-determined technological trajectory, is one of the larger issues that need to be addressed in media history.

More about the book Revolutions in Communication

As a professor teaching media history in the early 21st century, I often wished there was a textbook with a more inclusive scope. The idea of a “history of American journalism” seemed small and parochial. I was looking for a media history textbook that would:

As a professor teaching media history in the early 21st century, I often wished there was a textbook with a more inclusive scope. The idea of a “history of American journalism” seemed small and parochial. I was looking for a media history textbook that would:

1. Be useful to all communications students by covering the spectrum of disciplines – journalism, photography, film, advertising, public relations, broadcasting and new media;

2. Take history seriously by bringing the communications disciplines together to consider the way media is rapidly changing;

3. Provide tools for understanding technological change by introducing ideas like determinism versus social construction of technology; utopian versus declensionist rhetoric; McLuhan’s Tetrad and related thoughts about technological circumvention; and Arthur Koestler’s theory of social maturity and technology;

4. Include global perspectives, noting international connections between media people and organizations from the 18th to the 21st centuries.

5. Take advantage of new media capabilities to expand the book’s online links and offerings, for example, by providing easy access to public domain videos of ads, films, and TV programs.

I started sketching all this out on the web for my media history classes, with the thought of evetually publishing a book. However, an editor with Bloomsbury publishers happened to see the web site and asked if I would write the book for them. Now, I’m glad to say, the book is in its third edition.

By the way, Im happy to answer questions or get on a video conference with any classes using the book or teaching media history. Just give a shout at my email address, bill dot kovarik at the domain gmail dot com.

The basic approach

The historical narrative in Revolutions in Communication centers around technological change — a common thread that unites global media history and provides an alternative to nationalistic and professionally centered narratives that have guided media history in the past.

Since we live in revolutionary times, we ought to reflect and model those revolutionary new modes of communication in the way communication history is taught — and written. To take advantage of the new media, most of the video suggestions, readings, timelines and discussion questions have been placed on this book’s web site.

The web site also takes advantage of links to the international history of the media that is already begun on a variety of collaborative web sites such as Wikipedia.

It’s best to read history with some idea of what history is all about, and we begin with two items as part of a conceptual toolkit. The first is a quick overview of historians who exemplify different approaches to historical research and writing. The second is a glimpse at how historians have seen technology in general and media history in particular.

This book then proceeds on a mostly chronological basis through the four mass media revolutions: print, visual, electronic and digital.

Idea behind the book

The idea behind the combination book and web site was inspired by Vannevar Bush, who described the uses of a communications network in his famous 1946 “Memex” article.

… The historian, with a vast chronological account of a people, parallels it with a skip trail which stops only on the salient items, and can follow at any time contemporary trails which lead him all over civilization at a particular epoch. There is a new profession of trail blazers, those who find delight in the task of establishing useful trails through the enormous mass of the common record. The inheritance from the master [teacher] becomes, not only his additions to the world’s record, but for his disciples, the entire scaffolding by which they were erected.

One of the problems with teaching media history is that the structure of existing books tends to be heavily skewed toward transmitting the values of the media professions (particularly journalism) in one nation. The idea of this book and web site is to provide a larger scaffolding in order to provide structure for new paths through the common record.