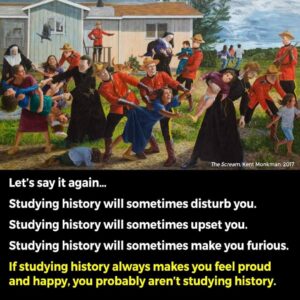

Kent Monkman’s painting depicts Canadian officials taking First Nations children to the Residential School System. The system operated through the 1970s. In May, 2021, ground radar showed that some of these schools are surrounded by hundreds of unmarked and unrecorded graves.

The fact that history is controversial means (at least) that it is important and that the questions are not settled. So, right off the bat, we can say history is not just a static collection of dusty old facts.

In the early 2020s, longstanding controversies over historical narratives erupted in the United States, Canada and Australia. Among the controversies were:

- The New York Times 1619 Project about how African American slavery has been depicted in standard historical textbooks;

- Remembering the Alamo is controversial in Texas, as elements of the “Anglo myth” turn out to be inaccurately biased against Hispanics.

- Native American and First Nations residential schools housed children forcibly taken from their parents and held by the US and Canadian governments. Unmarked mass graves were discovered on residential school sites in 2021. This controversy is still unfolding.

- “History Wars” is the term used in Australia over the treatment of Indigenous Australians and how to interpret events of the European colonization.

- An emerging understanding of the role of US newspapers in attacking (but also sometimes defending) African Americans in the post-Civil War era, as discussed in this book site on media history

The basic shape of the controversies involves challenges to historical myths that a dominant White culture had for many years accepted as complete and accurate.

In Sept. 2020, then-president Donald Trump created a committee to set the study of American history on the right course. The January 8, 2021 Report of the 1776 Commission was intended to summarize the founding principles of the US, to fend off “multiculturalism,” and to defend the Founding Fathers against charges of hypocrisy for both endorsing the ideal of equality on the one hand and supporting slavery on the other. “This charge is untrue, and has done enormous damage, especially in recent years, with a devastating effect on our civic unity and social fabric,” the commission said.

The concerns that led to the commission — for example, that American principles were being discarded in a wave of historical criticism — are now being reprised on a state level. For example, the very first thing Virginia Governor Glen Youngkin did after being sworn in on Jan. 15, 2022 was to issue Executive Order #1 prohibiting the teaching of divisive concepts in the state’s K-12 schools.

A companion Virginia bill (HB781) to prohibit the teaching of “divisive concepts” in schools was tabled in the 2022 Virginia legislature. The original bill required that students learn about the fundamental moral political and intellectual foundations of the country, including the Declaration of Independence, the United States Constitution … the first debate between Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass…” (The Lincoln – Douglass debates took place in 1858 between Lincoln and Illinois Senator Stephen Douglass. Frederick Douglass, a self-liberated former slave, was a leader of the abolitionist movement).

In 2021, at least four other states passed laws limiting discussions of race and similar issues in the classroom. Texas was considering a law that would limit discussions and lectures about the history of slavery and anti-Mexican violence. History teachers protested the new limits on academic freedom in June of 2021 and the American Association of University Professors called the bills “deeply troubling.” The goal of the bills is to thwart anti-racist progress by inappropriately using school curricula for political purposes, the AAUP said.

For conservatives, the point is that great American heroes are being pulled down and dishonored. Herodotus, who wrote The Histories about war between the Greeks and Persians almost 2,500 years ago, said he wanted to preserve the honor of Greek heroes. He would have understood the conservative perspective.

For centrists and liberals, the heroic approach to history ignores the mistakes and lessons that need to be learned. Most believe that state bans on critical race theory are reactionary defenses of mythology rather than an honest approach to history. (See this May 25 Guardian article). The problem with these laws, at least from the center and liberal perspectives according to an article in Education Week, is that current K-12 curricula already exclude the history and lived experiences of Americans of color, and the new bills cast a chill on African American history month and Martin Luther King Day in ways that are reactionary and retrogressive.

Adding more fuel to the controversy, new information about the 1921 Tulsa massacre, along with other deadly incidents involving black and indigenous peoples, has been surfacing in the 2020s. Officials in Canada and the US promised investigations into the unmarked graves surrounding indigenous “settlement schools.” These investigations, clearly, will make new contributions to the historical record that should be part of the ongoing historical record as taught to students.

Professional historians will tell you that there never has been one true version of history; it’s a much larger project than that. “History is the never-ending process whereby people seek to understand the past and its many meanings,” says the American Historical Society’s 2019 statement on standards of professional conduct.

The AHA statement goes on: “The institutional and intellectual forms of history’s dialogue with the past have changed enormously over time, but the dialogue itself has been part of the human experience for millennia. We all interpret and narrate the past, which is to say that we all participate in making history. It is among our most fundamental tools for understanding ourselves and the world around us.”

US Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, in promising an investigation into the residential schools, said: “Though it is uncomfortable to learn that the country you love is capable of committing such acts, the first step to justice is acknowledging these painful truths and gaining a full understanding of their impacts so that we can unravel the threads of trauma and injustice that linger. ”

The case for and against the 1619 project and university level critical race theory involves questions of which lens (or lenses) we use to evaluate known historical events. “The 1619 Project … aims to reframe the country’s history by placing the consequences of slavery and the contributions of black Americans at the very center of our national narrative,” says the project’s New York Times page. Students should learn why this is so and think about the range of reactions to the project.

What is history?

To begin with, history is memory, and it is just as important to a culture as it is to an individual. Reflecting on the past and preparing for the future are essential features of human intelligence. The discipline of history, then, requires us to examine both small events and sweeping trends, to suggest patterns that might be found in the record, and to constantly ask the vital question: why.

Historians search out facts and tell stories. Above all, they have a sacred duty to accuracy and the truth. Yet historians are free to explore and interpret without an expectation of exact answers. In this sense history is one of the Humanities, like law or literature. It is not a science, nor is it a social science. History is a separate discipline that plays by its own rules and answers to its own muse.

History is a powerful discipline, not only in terms of analytical ability and scope, but also in terms of the way it can be used (and / or misused) to legitimize present day political agendas and projects. In that sense, Eugin Weber once said history is “the dressing room of politics.” Or, as Christopher Clark said in The Iron Kingdom:

Those who seek to legitimate a claim to power in the present often have recourse to the idea of tradition. They decorate themselves with its cultural authority. But the encounter between the self-proclaimed inheritors of tradition and the historical record rarely takes place on equal terms.

Perhaps the most important first lesson about history, then, is that historians have motivations that influence the way they emphasize some facts instead of others. They usually write with a purpose in mind, and when groups of historians agree on a purpose, it is called a “school” of history. Historians who believe that history should unify a country are part of the “consensus school” of history, for example.

Historians and their motives

What good is history? What is it actually for, aside from putting undergraduate students to sleep? (Just kidding). The two strongest motives for historians are:

- To honor the heroes and

- To learn history’s lessons.

These were understood from ancient times and well expressed by two historians from Classical Greece:

- Herodotus (484 – 420 BCE) said he wrote history “… in the hope of … preserving from decay the remembrance of what men have done, and of preventing the great and wonderful actions of the Greeks and the Barbarians from losing their due meed of glory…” This is heroic history.

Thucydides (460 – 400 BCE) hoped his history would “be judged useful by those inquirers who desire an exact knowledge of the past as an aid to the interpretation of the future … I have written my work, not as an essay which is to win the applause of the moment, but as a possession for all time.” This is often called scientific history but, more accurately, inclusive history.

These two motivations are often at cross purposes. Heroic history inspires people, but it often omits the blemishes and controversies. On the other hand, inclusive history lets us learn from the past. It embodies the best-known idea about history expressed by George Santayana (1863 – 1952), who said: “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” Yet for many people, this approach can seem dry, uninspiring, iconoclastic, or even unpatriotic.

Heroic versus inclusive history

When students are first introduced to history in elementary and secondary school, the heroics are the focus of attention, and the controversies (even if mentioned) are lacquered over. Since there is rarely any advanced education in history, myths become commonplace in most cultures, and it often comes as a shock when modestly educated people discover that some views of history are more mythological than accurate.

Historic myths range from innocent tales to complex cultural lies. Sometimes they simply boost the image of a hero, like George Washington supposedly confessing to the destruction of a cherry tree, or US revolutionary Patrick Henry declaiming: “Give me liberty or give me death” (a statement recorded only decades after the fact from second-hand sources).

Many professional historians think these myths should be punctured. But historians do so at their peril, said Gil Klien

The myths are more beloved than the cold facts, and they are hard to kill. Many of them are designed to explain us as we wish to see ourselves. They establish the national character and set the standard for coming generations.

So heroic myths serve an important purpose; they can give culture a foundation, or, as historian Joseph Campbell said, “inspiration for aspiration.”

The danger of myths

Myths can strengthen a culture, but they can also be very dangerous. They can lead into the extremes of self-righteousness that create conditions for oppression, war, and genocide.

Imagine the venom injected into a culture by myths that describe some races or religions as sub-human, or that ascribe defeat to a “stab in the back” by unpatriotic elements of the society.(This includes the Dolchstoßlegende as in Germany after World War I and the dishonored spat-upon veteran myth in the US after the Vietnam war in the 1970s).

Imagine the damage done by the “Gone with the Wind” myth that described the American South fighting the US Civil War for noble motives.

Howard Zinn, in his People’s History, asked us to consider the heroic myth of Christopher Columbus in light of the extreme cruelty and genocide he personally promoted against Caribbean peoples.

These are examples of the many myths that have distorted history. The opposite is often called “scientific” history, and its main proponent was German historian, Leopold Von Ranke (1795 – 1886). He said the goal of history was to describe “the way things really were.” By that he meant that an account of the battle of Waterloo should be based on facts commonly accredited by French, German and English historians. It was, he believed, a scientific approach to history.

But if facts are solid, like bricks, the great themes of history are like architecture; they are designs based on cultural preferences made from facts. While no serious historian would doubt that French troops lost on the battlefield at Waterloo, by the same token, no one would suggest that the rise of Napoleon and achievements of the Napoleonic era could be seen in the same objective light by German, French or British historians.

If you read Von Ranke’s History of the Reformation in Germany, you find meticulous accuracy, great men and great institutions within a design that emphasizes conscience and sacrifice. Yet to a modern historian, Von Ranke’s neglect of the impact of the printing press might be a flaw. It’s difficult to imagine that today, with our awareness of the role of media, anyone today could write a history of the Protestant Reformation without mentioning the press. So objectivity and the scientific approach need to be considered not only from the standpoint of what is included, but also what is left out.

It’s no surprise, then, that the quest for scientific objectivity in history is often seen as quixotic. In That Noble Dream, Peter Novick describes attempts by American historians to first incorporate and then move away from Von Ranke’s presumed objectivity. Many historians abandoned this constricted view of objectivity and devoted their histories to nationalistic and moral purposes. These historians included Charles Beard (1874 – 1948) and Lord John Edward Emerich Acton (1834-1902).

Acton’s most famous aphorism is: “Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.” The phrase comes from correspondence about the doctrine of papal infallibility and the idea that great men should not be judged harshly because they were dealing with great issues. On the contrary, Acton said. Great men should be held up to an even higher standard due to the suspicion that they had become corrupted by power.

The moral judgement that Beard or Action offered were in some respects a return to mythology. And that mythological history (as contemporary sports historian John Thorn said) is “the people’s history,” which historians are obliged to embrace. (For example, in the great western-genre movie “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance,” a journalist finds his version of a territory’s emergence into statehood was just a myth, and the reality was far more nuanced and interesting But his editor says: “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.” )

But Howard Zinn would say that a people’s history is far more than an account that tugs on the heart strings of culture or patriotism. A peoples history describes the lives of the powerless as well as the powerful, and rejects the myth-making heroics that can obscure the immorality of the powerful. It is, at the very least, an inclusive history.

History and ethics

According to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, there is an ethical dimension that necessarily entails any quest for historical knowledge.

Of course, historians have obligations of truthfulness and objectivity; peoples have obligations of honest recognition; and nations have obligations of memory and reconciliation. But there is also a broader ethical obligation:

The facts of genocide and other crimes against humanity make it clear that there are moral reasons for believing that all of humanity has a moral responsibility to attempt to discover our past with honesty and exactness. In particular, the facts of past horrific actions (genocide, mass repression, slavery, suppression of ethnic minorities, dictatorship) create a moral responsibility for historians and the public alike to uncover the details, causes, and consequences of those actions

Whig history

Another dimension of controversy within history involves the influence of “presentism,” or the tendency to see the past through the optics of the present. For instance, most people have heard of the “fog of war.” A whig historian might be one who does not recognize that in the “fog of war,” historical figures had to make decisions based on imperfect knowledge.

The historian who first pointed this out, Herbert Butterfield (1900 – 1979), objected to the way historians would “write on the side of Protestants and Whigs, to praise revolutions, provided they have been successful, to emphasize certain principles of progress in the past, and to produce a story which is the ratification if not the glorification of the present.” For example, ideas like the inevitable progress of history, or the constant expansion of personal freedom and human rights, may be seen as “Whig” history, even if, in some countries, and in some eras, these ideas contain more truth than myth.

Thomas Macaulay, (1800 – 1859) saw these extremes as errors, and advised a balanced approach:

There are two opposite errors into which those who study the annals of our country are in constant danger of falling, the error of judging the present by the past, and the error of judging the past by the present. The former is the error of minds prone to reverence whatever is old, the latter of minds readily attracted by whatever is new. The former error may perpetually be observed in the reasonings of conservative politicians on the questions of their own day. The latter error perpetually infects the speculations of writers of the liberal school when they discuss the transactions of an earlier age. The former error is the more pernicious in a statesman, and the latter in a historian. (The History of England, from the Accession of James II — Volume 2)

Macaulay aside, whig history is not always pernicious — in fact, the historical focus on democratic reform in US and UK histories was designed rather deliberately to keep that historical frame in view as an aide to present-day political growth and reform. Yet it tended to omit irregularities and present history in a linear form.

Cultural history

In recent years, many historians have moved away from objective and progressive national histories, focusing instead on cultural history or other smaller topics. Cultural history might involve the history of ideas, history of technology, women’s history, black history, environmental history and many other areas not yet explored.

To some, such as Francis Fukuyama (1952 – present) and Jean Baudrillard (1929 – 2007), the collapse of ideology or even the end of an idea of historical progress represents the “end of history.” According to Baudrillard, this comes from the abandonment of utopian visions shared by both the right and left wing political ideologies.

And yet, ideas about utopian futures re-emerged in force with the advance of communications technologies, living on in the visions of social networks and free cultures described by Vannevar Bush, John Perry Barlow, Howard Rheingold, Richard Stallman, and others engaged in the digital revolution.

In any event, the continued relevance of historical interpretation for cultural and national identity makes the ‘end of history’ idea seem at least premature, according to Jeremy M. Black in the 2015 book, Clio’s Battles.

How is media history different?

Historians have always seen a strong role for media in the larger sphere of national histories, and it would be unlikely that any historian would overlook the role of printers like Benjamin Franklin in enabling the American Revolution of the 1770s, or of radio news as a catalyst of public opinion during the 1940s, or of television images to bring home the suffering of Civil Rights demonstrators during the 1960s.

Among early American media histories are Isaiah Thomas‘ History of Printing in America and James Parton’s Life of Horace Greeley (1855). Like many subsequent histories, both took a “whiggish” approach that presumed a history of progress towards freedom. The same idea remained in the heart of the narrative until the 1970s, when the foundations of objectivity were shaken to the core by events inside and outside the world of the news media. (Footnote Carey p79) Communications scholar James W. Carey challenged journalism historians to go beyond their identification with the press and, as one suggestion, to focus on the development of consciousness as expressed in the news report. (One upshot of that idea was Mitchell Stephens’ book, A History of News. )

One school of historical thought goes considerably further than giving media a role in national histories by placing communications history at the center of civilization. For example:

Harold Innis (1894 – 1952) was an economic historian who explored the idea that cultures using durable media tended to be biased (oriented) towards time and religious orthodoxy (Egypt, Babylon), while, on the other hand, cultures with flexible media (Rome, Greece, modern) were biased towards control of space and a secular approach to life.

Marshall McLuhan (1911 – 1980) was a media critic who was strongly influenced by Innis and also put communication at the center of history. McLuhan saw international broadcast media connecting through satellites in the 1950s and 60s, and described the new media landscape in terms of a “global village.” He also considered the idea of media as an extension of human thinking. He is probably most famous for the statement that “the medium is the message,” which, in other words, means that the medium is has a strong influence on the message and the type of thinking that creates the message.

Communications theorist James W. Carey saw McLuhan’s relatively optimistic ideas about media technology as something of a reaction to the pessimism expressed by others, especially British historian Lewis Mumford. McLuhan envisioned electronic media liberating users from the sensory limitations of the past, while Mumford “recognized the paradox of electrical communication: that the media of reflective thought — reading writing and drawing — could be weakened by television and radio; that closer contact did not necessarily mean greater peace; that the new inventions would be foolishly overused… ” (Carey, 1997, p. 49).

While electronic media may well be liberating in some ways (for example, the social impact of television on the civil rights movements in the US), experiments with MRI imaging in the early 21st century showed that special parts of the brain are engaged by the process of reading. So the idea of “cool” media (film, television) involving less processing, and “hot” media (such as reading) involving more mental processing turns out to have been essentially correct, even if McLuhan ascribed those attributes to the media rather than to the media user.

McLuhan has also pointed out that new communications technologies change and grow in familiar patterns that can be mapped out in what he called a “tetrad” of four effects. A new medium can 1) enhance 2) obsolete 3) retrieve and 4) reverse. For example, the arrival of radio enhanced news and music, it obsolesced (or made less prominent) print and visual media; it retrieved the spoken word and music hall shows; and it reversed (when pushed to its limits) into television. (McLuhan, 1988 and 89) We might also say that television enhanced the visual, obsolesced the audio, retrieved theatrical spectacle, and reversed into “500 channels with nothing on.”

Social theories of the media

Another part of our theoretical toolkit involves normative social theories that have critiqued and challenged the mass media. (Normative here means what the media ought to be doing). We begin with an overview that describes a continuum between liberal and critical concepts of the media. On the one hand, liberal democrats have seen the mass media as an agent of progressive social change, a self-righting component of a democracy. On the other hand, sociologists and critical theorists have seen the mass media’s production of culture as a place for the greater contest of ideas (ideational conflict) and, sometimes, as an instrument of class control. Illustrating this range of social theory, we have:

• Liberal democrats like Walter Lippmann held the press up against the idea that the press is part of a system of checks and balances (“the original dogma of democracy”) in his 1921 book, Public Opinion. Lippmann also described four stages of media progress, from authoritative, to partisan, to commercial, and then to a state he called organized intelligence.

Other important media critics include:

- Upton Sinclair, who wrote The Jungle (about the Chicago meat industry), compared journalism to prostitution in The Brass Check, a strong criticism of the American media in the 1920s.

- Hilare Belloc wrote The Free Press – a scathing attack on the British press in 1917 from a conservative perspective.

- A.J. Liebling, a media critic with the New Yorker from the 1930s to the 1960s

- I.F. Stone, and George Seldes, independent newsletter editors and press critics in the 1950s and 60s.

- Ben Bagdikian, an American academic who criticized the “media monopoly.”

- Niel Postman, an American academic who saw the media “Amusing Ourselves to Death.”

- Robert W. McChesney wrote “Digital Disconnect.”

• Sociologists like Max Weber and Michael Schudson use an ideational model as the appropriate focus for a critical examination of the media, observing, for example, the clash of ideas around effective social reform movements.

• Communications theorists like Michel Foucault often use discourse analysis to understand the information content and structure of mainstream cultural products and “subjugated knowledges.”

• Critical theorists from Europe, especially Theodor W. Adorno, Walter Benjamin, and Jurgen Habermas and others from the Frankfurt School, who saw the conflict of classes as the major theme of media analysis and observed that mass media was structured to subvert identity and assimilate individuality into the dominant culture. Noam Chomsky, an American academic expert in linguistics and “libertarian socialist” is sometimes included in this group as a critic who sees media as little more than an instrument for generating propaganda in support of ruling elites.

Camille Paglia , an historian at the University of the Arts in Philadelphia. had this to say about Marshall McLuhan

It’s just shocking to me that we’ve had a period over the last 20 years where a bunch of French theorists who know nothing about media have been the dominant god figures of the Ivy League and all other kinds of chic campuses across the country. It just amazes me because none of the French theorists, none of the experts in post-structuralism know anything about media. Nothing whatever. These are figures that pre-date World War II in their thinking, they were untouched by media in the North American sense, in the kind of all-encompassing, total-immersion sense that we know it here, even the kinds of thinking that you get out of the so-called Frankfurt School, associated with Adorno, dates to the 1930s in Germany! It’s amazing to me! But right now if you go to any of the cutting edge campuses (supposedly), in this country, you will get mass media fed to you through a number of ridiculous sieves. You will get it either through pro-structuralism, you will get it through the Frankfurt School, or through semiotics, all of which to me is a big pile of manure that we have to just flush! We already had a North American shaman of media, and that was McLuhan … My theory is this: that the people who are most affected by McLuhan did not go on to graduate school.

Paglia shares a “religious interpretation” of sensory media with McLuhan, in that she sees religious orthodoxy being opposed in three historical epochs: the Renaissance, the Romantic era, and the era of mass culture.

ALSO SEE

Native American adoption laws are controversial – The Guardian, Aug. 21, 2021.

Philosophy of History, the Stanford Encyclopedia of History, 2020: “The facts of genocide and other crimes against humanity make it clear that there are moral reasons for believing that all of humanity has a moral responsibility to attempt to discover our past with honesty and exactness. In particular, the facts of past horrific actions (genocide, mass repression, slavery, suppression of ethnic minorities, dictatorship) create a moral responsibility for historians and the public alike to uncover the details, causes, and consequences of those actions.

MORE

(Ed’s note: This part was excised from this page when a 2013 video from Chronicling America was removed from YouTube).

Uncovering history is exciting, says Ed Ayers of the University of Richmond in a 2013 Chronicling American video, in which he spoke about how he felt, uncovering the past through the pages of old newspapers:

“Oh my God, this stuff actually happened, and it all happened at the same time, and people didn’t know they were living in history, and they didn’t know how things were going to turn out — What are we going to do about that?”

“I told my mom I was going to study history and she said, ‘what for, we already know what happened,’ and I read those newspapers and I said ‘Oh no we don’t.'”

An eloquent speaker and historian, more of Ed Ayers lectures are available with a quick YouTube search. Here’s one: