Context: The US Civil War is well known to American students, but the Crimean War between Britain and Russia, fought only a few years beforehand, is not. The war was mostly over trade in the Black Sea, and Sebastopol is a port town on the Crimean peninsula. Although only one of many small wars over imperial power in the region, it is remembered for the annihilation of a large light cavalry brigade which was mistakenly ordered to charge without support directly into a heavily fortified position. Of the 600 who charged, only about 200 returned. This report in the Times infuriated many and led to a change in government. The incident became a celebrated poem by Tennyson with the famous line: “Theirs not to reason why, theirs but to do and die …” It was also the subject of a Kipling poem and several Hollywood movies.

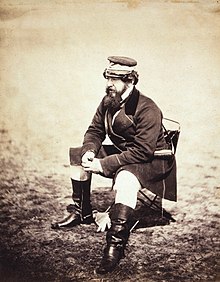

William Howard Russell’s dispatch took about a month to reach the London Times. It was written in something of a hurry, but probably sent on a packet ship the day after the conflict. Consider his floridly verbose lead, which was typical just before the widespread use of the telegraph, and his partisanship. But also consider also his attention to detail, colorful description and use of an attributed simile.

On the other hand, consider Henry Villard’s terse prose and the tacked-on paragraphs at the end of the story, as new reports came in by telegraph just in time for the morning edition of the paper.

(Note: Chip Scanlon of the Poynter Institute had a similar take on the influence of the telegraph on the inverted pyramid.)

BeforeTimes of London, Oct. 25, 1854 The Heights Before Sebastopol  William Howard Russell, London Times If the exhibition of the most brilliant valor, of the excess of courage, and of a daring which would have reflected luster on the best days of chivalry can afford full consolation for the disaster of today, we can have no reason to regret the melancholy loss which we sustained in a contest with a savage and barbarian enemy. I shall proceed to describe, to the best of my power, what occurred under my own eyes, and to state the facts which I have heard from men whose veracity is unimpeachable, reserving to myself the right of private judgment in making public and in suppressing the details of what occurred on this memorable day… [After losing ground to a British force half its size, the Russians retreated to the heights above Sebastopol, a port town on the Black sea] At 11:00 our Light Cavalry Brigade rushed to the front… The Russians opened on them with guns from the redoubts on the right, with volleys of musketry and rifles. They swept proudly past, glittering in the morning sun in all the pride and splendor of war. We could hardly believe the evidence of our senses. Surely that handful of men were not going to charge an army in position? Alas! It was but too true — their desperate valor knew no bounds, and far indeed was it removed from it so-called better part — discretion. They advanced in two lines, quickening the pace as they closed towards the enemy. A more fearful spectacle was never witnessed than by those who, without the power to aid, beheld their heroic countrymen rushing to the arms of sudden death. At the distance of 1200 yards the whole line of the enemy belched forth, from thirty iron mouths, a flood of smoke and flame through which hissed the deadly balls. Their flight was marked by instant gaps in our ranks, the dead men and horses, by steeds flying wounded or riderless across the plain. The first like was broken — it was joined by the second, they never halted or checked their speed an instant. With diminished ranks, thinned by those thirty guns, which the Russians had laid with the most deadly accuracy, with a halo of flashing steel above their heads, and with a cheer which was many a noble fellow’s death cry, they flew into the smoke of the batteries; bgut ere they were lost from view, the plain was strewed with their bodies and with the carcasses of horses. They were exposed to an oblique fire from the batteries on the hills on both sides, as well as to a direct fire of musketry. Through the clouds of smoke we could see their sabers flashing as they rode up to the guns and dashed between them, cutting down the gunners as they stood. The blaze of their steel, like an officer standing near me said, “was like the turn of a shoal of mackerel.” We saw them riding through the guns, as I have said; to our delight, we saw them returning, after breaking through a column of Russian infantry and scattering them like chaff, when the flank fire of the battery on the hill swept them down, scattered and broken as they were. Wounded men and dismounted troopers flying towards us told the sad tale — demigods could not have done what they had failed to do. At the very moment when they were about to retreat, a regiment of lancers was hurled upon their flank. Colonel Shewell, of the 8th Hussars, saw the danger and rode his men straight at them, cutting his way through with fearful loss. The other regiments turned and engaged in a desperate encounter. With courage too great almost for credence, they were breaking their way through the columns which enveloped them, where there took place an act of atrocity without parallel in modern warfare of civilized nation. The Russian gunners, when the storm of cavalry passed, returned to their guns. They saw their own cavalry mingled with the troopers who had just ridden over them, and to the eternal disgrace of the Russian name, the miscreants poured a murderous volley of grape and canister on the mass of struggling men and horses, mingling friend and foe in one common ruin. It was as much as our Heavy Cavalry Brigade could do to cover the retreat of the miserable remnants of that band of heroes as they returned to the place they had so lately quitted in all the pride of life. At 11:35 not a British soldier, except the dead and dying, was left in from of those bloody Muscovite guns… |

AfterNew York Herald, July 22, 1861. The Disaster at Bull’s Run, Washington  Henry Villard, New York Herald Our troops, after taking three batteries and gaining a great victory at Bullrun, were eventually repulsed, and commenced a retreat on Washington. After the latest information was received from Centerville, at half past seven last night, a series of unfortunate events took place which have proved disastrous to our army. Many confused accounts are prevalent, but facts enough are known to warrant the statement that we have suffered, severely on account of a most unfortunate occurrence, which has cast a gloom, over the retreating army and excited the deepest melancholy throughout Washington. The carnage is very heavy on both sides. Our Union forces were advancing upon the enemy and taking his masked batteries gradually but surely, by driving the rebels towards Manassas Junction, when they seem to have been reinforced by twenty thousand men under Gen. Johnston, who, it is understood, then took command and immediately commenced driving us back. We were retreating in good order, the rear well covered with a solid column, when a panic among our troops suddenly occurred, and a regular stampede took place. Before that all our military operations went swimmingly on, and Colonel Alexander was about erecting a pontoon across Bull run. The enemy were seemingly in retreat, and their batteries, one after another, being unmasked, when a considerable consternation broke out among our teamsters, who had incautiously advanced immediately after the body of the army, and lined the Warrentown road. Their consternation was shared in by numerous civilians who were on the ground, and for a time it seemed as if our whole force was falling back. Many baggage wagons were emptied, and their horses galloped across the open fields, all the fences of which were torn down to allow them a more rapid retreat. A perfect panic prevailed among the wagoners, which was communicated to the vicinity of Centreville, and every available conveyance was seized upon by agitated citizens who had come out to see the battle. Wounded soldiers cried on the road side for assistance, but the alarm was so great that numbers were passed by unheeded. Several similar alarms occurred on previous occasions, when a charge of the rebel batteries rendered necessary the retirement of our artillery, and it is most probable that the alarm was owing to the same fact. The reserve force at Centreville was immediately brought up, Col. Einstein’s Twenty-seventh When our courier left, at half past four, it was in the midst of this excitement. The new masked batteries had been opened by the rebels on the left flank, and that portion of the division had its line broken, and demanded immediate reinforcement. The right flank was in good order. The battery erected on the hillside directly opposite the main battery of It was known to our troops at the time of the battle yesterday that General Johnston had formed a connection with General Beauregard on the night of the first action at Bull Run. Our men could distinctly hear the cars coming into Manassas Junction, and the cheers with which the rebels hailed their newly arriving comrades. They knew that the enemy was our superior in numbers and in their own position. These facts were further confirmed by prisoners taken and deserters and spies, but these facts were not probably known at Washington, and the officers in leading our men into action only obeyed orders. General McDowell undertook to make a stand in the vicinity Beyond Fairfax Court House the retreat was continued until In the retreat many of the troops fell on the wayside from The road from Bullrun was strewed with knapsacks, arms General McDowell was in the rear of the retreat, exerting He was completely exhausted, having slept but little for Gen. Schenck, as well as the older field officers, acted It was the arrival of fresh reinforcements to the enemy in The enemy before now might perhaps have more to boast of if they had followed up their advantage last night. From the statements of Quartermaster Pryor, a rebel GriffinWest Point battery was taken by the enemy, and The Rhode Island battery was taken by the rebels at the The Sixty-ninth and other regiments frightfully suffered in It is reported that the Black Horse Cavalry made an attack The Seventy-first New York regiment lost about half their Nearly all the provision trains belonging to the United Colonel Marston New Hampshire regiment reaches here this morning. He was wounded. Colonel Heintzelman was also wounded in the wrist. In addition to those reported yesterday, it is said that Col. Farnham and Major Lozier, of the Zouaves, are not killed, but badly wounded. Colonel Hunterdivision suffered most severely. Colonel Heintzelman was wounded in the arm. The bullet was extracted while he was still upon his horse. Lieut. Henry Abbott, of the Topographical Engineers, has Colonel Marston, of the Second New Hampshire regiment, lost Captain Ricketts, of the artillery, two New York regiments, The city this morning is in the most intense excitement. Such of the wounded as were brought to the Centreville Wagons are continually arriving, bringing in the dead and It is probable that the number of killed and wounded is The lowest estimate may be placed at 4,000 to 5,000. It is represented in many quarters that the Ohio regiments showed the greatest consternation, probably from want of confidence inn their commanding officers. It is known that on the day previous to the battle a large It is supposed here today that General Mansfield will take Large rifled cannon and mortars are being rapidly sent over The troops are resuming the occupation of the It is vaguely reported that General Pattersondivision It is also reported that four thousand of our troops have |