- Part 1 – Introduction

- Part 2 – Media in war and peace (This page)

- Part 3 – Non-violent communication

- Part 4 – Peace Journalism

—————

Historically, the role of the press in promoting war or enhancing prospects for peace has been significant. Here are some examples:

Peloponnesian war, Greece, 411 BCE

“If great enmities are ever to be really settled, we think it will be not by the system of revenge and military success, and by forcing an opponent to swear to a treaty to his disadvantage, but when the more fortunate combatant waives his privleges, to be guided by gentler feelings, conquers his rival in generosity and accords peace on more moderate conditions than he expected.”

— The world’s first war correspondent, Thucydides, around 400 BCE.

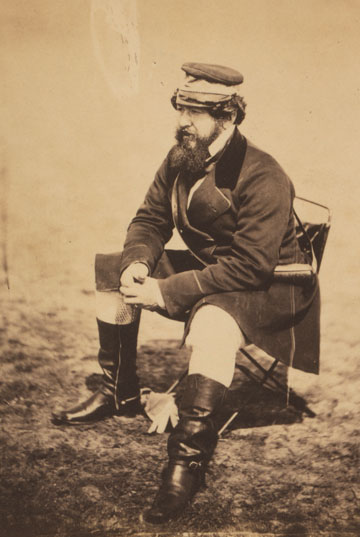

Crimean war (1853 – 1856)

In one of the first instances where war reporting created an anti-war public reaction, London Times correspondent William Howard Russell reported on the Charge of the Light Brigade.

In one of the first instances where war reporting created an anti-war public reaction, London Times correspondent William Howard Russell reported on the Charge of the Light Brigade.

If the exhibition of the most brilliant valor, of the excess of courage, and of a daring which would have reflected luster on the best days of chivalry can afford full consolation for the disaster of today, we can have no reason to regret the melancholy loss which we sustained in a contest with a savage and barbarian enemy. (William Howard Russell, The

Times, London, November 13, 1854)

The outrage over the miscommunication and slaughter of the British light cavalry unit was an unexpected consequence of the new power of the news media to criticize, rather than promote, wars and revolutions.

US Civil war (1861 – 1865)

Although the press of the US was not uniform in its support of the war, most of the dissenting or “copperhead” press simply demanded compromise. There were a few, such as Hezekiah Niles, who in the pre-war years thought that conflict could be averted . Niles is remembered as the editor who tried to stop the Civil War, Niles used his nationally circulated magazine to mediate the North-South crisis during its critical formative stages in the 1830s, Niles presenting a multi-faceted plan for changing the plantation economy.

In hundreds of editorials and in his selection of thousands of factual news items, Niles envisioned the South with a strong middle class, diversified agriculture, protection for new manufacturing, and universal education of African Americans leading towards eventual emancipation. This program was an extension of the “American System” supported by Niles and two other prominent figures of the era, Kentucky Sen. Henry Clay and economist Mathew Carey, and later carried on as the “activist government” thread by Abraham Lincoln, the Republican Progressive movement of 1900 – 1912, and picked up by Democrats Woodrow Wilson, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Lyndon Johnson.

It was this exact vision of a rebuilt American South that was articulated by Atlanta’s great editor, Henry Grady, in 1888. Grady’s “New South” was really the old vision of an alternative South that was perfectly visible to Niles — and his readers — decades before the guns opened fire on Fort Sumter.

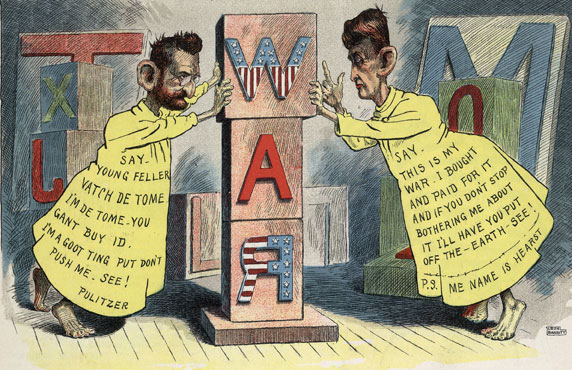

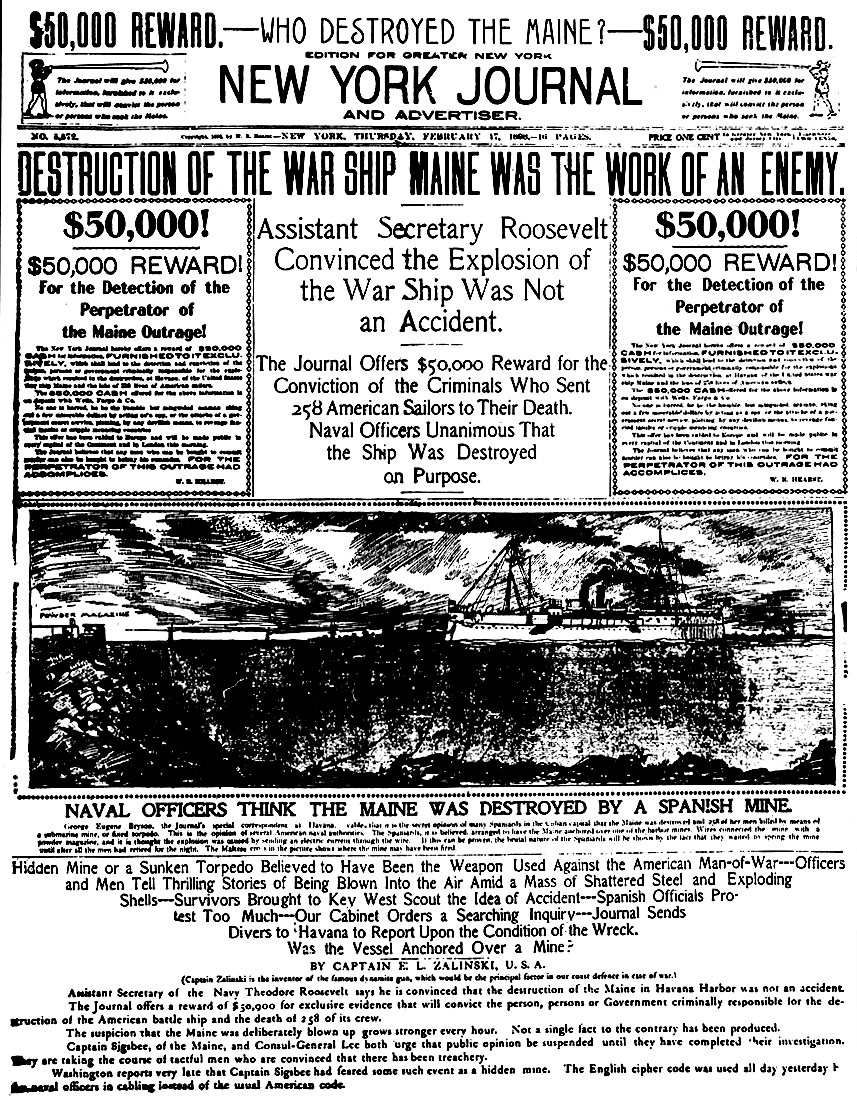

Spanish American war (1898 – 1900)

William Randolph Hearst and his rival, Joseph Pulitzer, pressured the US government into war against Spain in 1898. The affair was the low point of what came to be called “yellow journalism,” named for the yellow ink used to color a comic character called the “Yellow Kid.”

William Randolph Hearst and his rival, Joseph Pulitzer, pressured the US government into war against Spain in 1898. The affair was the low point of what came to be called “yellow journalism,” named for the yellow ink used to color a comic character called the “Yellow Kid.”

In the fall of 1896, Hearst hired a reporter (Richard Harding Davis) and an artist (Frederick Remington) to cover an insurrection in Cuba against the colonial Spanish government. The insurrection was bitterly fought, with atrocities on both sides, and 200,000 Spanish troops moved tens of thousands of civilians into “ re-concentration” camps where many died of disease. The drawings and stories shocked Americans when they ran in 1897, and Hearst, indignant at the brutality, kept up the pressure.

According to one of the Hearst legends, Remington wired Hearst to say there was nothing going on, and Hearst wired back “You furnish the pictures, Ill furnish the war.” The exchange is one of the best remembered anecdotes of journalism and seems in character as a description of Hearst’s arrogance. But Hearst later denied writing it, and it was true, at least, that Hearst had already inserted his newspaper into a foreign intrigue in a way that no American newspaper publisher had ever before dared.

When the battleship USS Maine blew up in Havana, Cuba on February 15, 1898, the incident took over the front page of the newspaper for days, with headlines blaring “Spanish Treachery” and “Work of an Enemy.” Hearst offered a $50,000 reward “for the detection of the perpetrator of the Maine outrage.” Pulitzer also featured full front page coverage of the disaster, but emphasized the loss of life and noted that the explosion was “Caused by Bomb or Torpedo.” The Spanish–American war and the invasion of Cuba in the spring of 1898 were not caused by Hearst’s newspaper coverage, but it was a factor. Hearst’s enthusiasm for the war also drew him to Cuba during the war, where he faced gunfire and even personally captured a group of unarmed Spanish sailors—making headlines in the process.

Boer War (1899 – 1902)

Alfred Harmsworth, publisher of the London Daily Mail and Daily Mirror, took a page from Hearst’s book to promote the Boer War , in which British forces defeated Dutch settlers who were seeking autonomy from the British colonial system.

Alfred Harmsworth, publisher of the London Daily Mail and Daily Mirror, took a page from Hearst’s book to promote the Boer War , in which British forces defeated Dutch settlers who were seeking autonomy from the British colonial system.

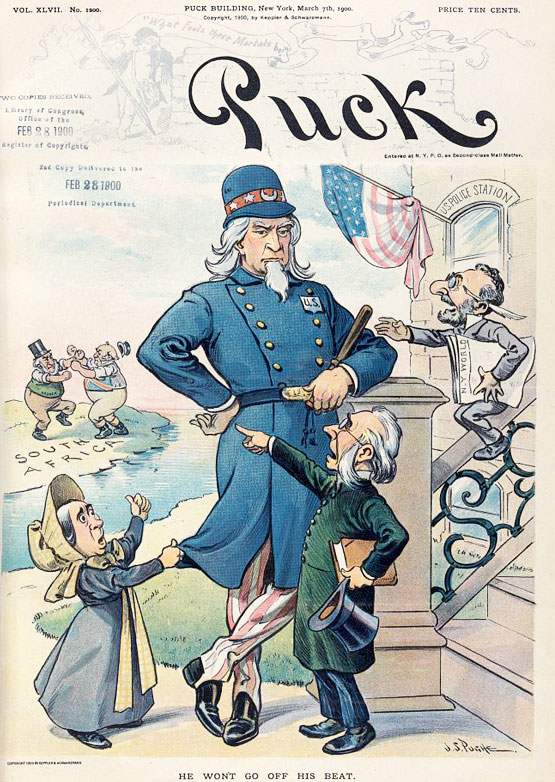

Pulitzer’s enthusiasm for the Spanish American war seems anomalous compared to his role in other wars. For example, he wanted the U.S.to intervene to stop the war Boer War, as in this Puck cartoon of 1900, where a resolutely isolationist Uncle Sam is refusing to get involved, despite Pulitzer’s nagging. But Pulitzer also worked hard to keep America and Britain out of war in the early 1890s. The two nations were on the verge of armed conflict over a territorial dispute in South America and the Monroe Doctrine. Pulitzer used every means possible to avert the war and remind Americans of how much they had in common with Great Britain.

World War I

“WWI was the most murderous, mismanaged butchery that has ever taken place on earth. Any writer who said otherwise lied. So the writers either wrote propaganda, shut up, or fought” — Ernest Hemingway

“WWI was the most murderous, mismanaged butchery that has ever taken place on earth. Any writer who said otherwise lied. So the writers either wrote propaganda, shut up, or fought” — Ernest Hemingway

George Seldes, a reporter with the Atlanta Constitution and other newspapers, wrote of one important incident illustrating the counterproductive nature of front line censorship.

On November 12, 1918, the day after Armistice, Seldes and three other reporters drove through German lines and found German Field Marshall Paul von Hindenburg. “The American attack won the war,” Hindenburg told the

correspondents. The incident is important, Seldes said, because Hindenburg acknowledged that the war was won in the field, and did not make excuses or blame some kind of betrayal from the home front (Seldes, 1987). When Seldes and the others filed their stories, US censors in Paris blocked them.

Later, the Nazis would use the Dolchstoss, the “stab-in-the-back” myth by Jews in Germany, to explain away the German defeat in World War I. “If the Hindenburg confession had been passed (by US censors), it would have been headlined in every country . . . and become an important page in history,” Seldes said later. Of course no one realized the full significance of the episode at the time, but in retrospect, Seldes said: “I believe it would have destroyed the main planks of the platform on which Hitler rose to power”

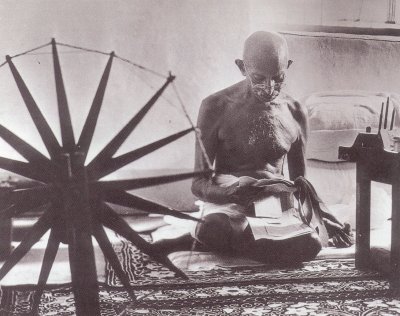

The press in India’s nonviolent revolution (1917 – 1946)

After studying law in Britian, Mahatma Gandhi started his professional career in South Africa, where he founded a newspaper called Indian Opinion in 1903. He thought it was critical to have the publication in order to explain Satyagraha, the principle behind nonviolent social revolution. Later, when he returned to India, Gandhi founded the weekly Young India to promote views on political reform, religious tolerance and economic self-sufficiency for India. The publication changed its name to Harijan, which meant “Children of God.” It was published from 1919 through 1948.

Gandhi also edited four other journals during his long career. “Week after week I poured out my soul in columns expounding my principles and practices of Satyagraha,” Gandhi said. “The journal became for me a training in self-restraint, and for friends a medium through which to keep in touch with my thoughts.” In his autobiography, Gandhi said that “Satyagraha would probably have been impossible without Indian Opinion.” Journalism taught Gandhi the discipline of being fair and remaining cool even when he was attacked, said Shall Sinha, a Gandhi biographer. “It helped him clarify his own ideas and visions, to stay on track, to be consistent, to assume full accountability for his actions and words . . . The newspapers brought Gandhi in close communication with many deep thinkers and spiritual leaders. It kept broadening his horizon everyday. Gandhi pursued journalism not for its sake but also as an aid to what he had conceived to be his mission in life: to teach by example and precept.”

It’s interesting that Chicago Tribune correspondent William L. Shirer followed Gandhi for several years in India. “For those of us who glimpsed, however briefly, Gandhi’s use of (Satyagraha); and who had the luck, for however short a time, to feel his greatness . . . it was an experience that enriched and deepened our lives as no other did.” That experience, he said, helped him find the moral courage to describe the terror creeping over Germany in the 1930s when he worked for the Associated Press and CBS radio.

World War II

The threat to freedom was never more clear than in the 1940s, and news correspondents willingly lent their talent to the allied war effort to stop fascism in Germany, Italy and Japan.

The African American press was initially divided over support for World War II. After all, in World War I, critical reporting on military race riots landed a black editor in jail under the Sedition Act. Simple concern for social reform led to investigations for disloyalty by the FBI (Washburn, 1986). The African American press settled on a dual strategy—the “ Double V” campaign—which called for victory over the enemies of democracy both abroad and at home.

Reconstructing the German and Japanese press after the war was a special problem. A program to pay thousands of independent journalists and rebuild newspaper publishing operations cost the US government millions of dollars, according to historian Robert McChesney. At one point in the summer of 1945, then-general Dwight D. Eisenhower “called in German reporters and told them he wanted a free press. If he made decisions that they disagreed with, he wanted them to say so in print .. ” Gen. Douglas MacArthur took the same approach in Japan. “Eisenhower and MacArthur did not wait for the market to come up with fixes,” McChesney said. “The work of establishing a free and independent press was too vital a task for that.”

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wW1i-R39AAk&feature=related]

Civil Rights

One of the finest moments in the history of the mainstream American press was its response to the civil rights movement that culminated in the 1950s and ’60s. As African Americans pressed for equality with bus boycotts, lawsuits, lunch counter sit-ins and other nonviolent tactics, the mainstream press wondered how to cover rapidly unfolding events.

At first the media settled into what seemed at first to be a gentlemanly debate over schools and desegregation in the 1950s. But by misreading the sentiments of political extremists, the Times “failed to see that the extremes would soon be in control,” said Gene Patterson and Hank Klibanoff in The Race Beat, a 2006 history of civil rights news coverage. The mainstream press, like the country, was divided on the civil rights movement.

Editors James J. Kilpatrick of the Richmond (Va) News and Thomas Waring of the Charleston (SC) Courier advocated “massive resistance” to integration and encouraged Southerners to fight for states rights. On the other hand, more temperate Southerners advised gradual change. These included Atlanta Journal editor Ralph McGill, Greenville, Mississippi, editor Hodding Carter, and Little Rock editor Harry Ashmore.

Ralph McGill was especially known for crafting carefully balanced editorials to depict the civil rights movement as a sometimes uncomfortable but necessary and even inevitable process—a process that would help build a South that was too busy, and too generous, to hate. After an Atlanta bombing, McGill wrote in a 1959 Pulitzer Prize winning editorial: “This . . . is a harvest of defiance of the courts and the encouragement of citizens to defy law on the part of many Southern politicians.”

McGill’s protégé, Gene Patterson, made similar appeals. After Dr. Martin Luther King’s assassination in 1968, Patterson wrote a front page editorial in the Atlanta Journal calling on white Americans to cease “the poisonous politics of hatred that turns sick minds to murder. Let the white man say, ‘No more of this ever,’ and put an end to it—if not for the Negro, for the sake of his own immortal soul.”

In the end, the success of the nonviolent civil rights movement was closely connected with the media’s ability to witness events. “If it hadn’t been for the media—the print media and the television—the civil rights movement would have been like a bird without wings, a choir without a song,” said John Lewis in 2005 (Roberts and Klibanoff, 2007). Eventually, even conservative editors like Kilpatrick admitted that they had been wrong about civil rights. In reporting the suffering of American civil rights demonstrators, the press came to be regarded with gratitude as an agent of national reconciliation.

At a time when American soldiers were fighting communism in Vietnam, the images of embattled civil rights demonstrators were deeply mbarrassing for the administration of President Lyndon Johnson. A renewed commitment to civil rights, and national legislation stiffening laws against voter intimidation, were among the direct results of the new awareness brought about by television. “The ascendancy of television as the new arbiter of public opinion became increasingly apparent at this time to civil rights leaders and television news directors alike,” according to the Museum of Broadcast Communications. Yet the television audiences in the South closest to events of the civil rights era were often kept in the dark. Many southern TV stations routinely cut national network feeds of civil rights coverage, often pretending that they were having technical difficulties. Newspapers were also neutral or quite often hostile to civil rights in the 1950s and 60s, and usually omitted wire service coverage of civil rights issues unless there was a white “backlash” angle. (Important exceptions included the Atlanta Constitution or the Greenville, MS, Delta Democrat-Times).

While newspaper publishers were free to do as they pleased under the First Amendment, broadcasters had an obligation to fairness under Fairness Doctrine, and their station licenses were controlled by the federal government. Broadcasting offered more opportunity to force change than the print media.

One significant moment was the revocation of the television station license for WLBT of Greenville, Mississippi, as noted in this overview of the case and an interview in 2005.

Vietnam

National reconciliation never really took place following the Vietnam War. Unlike the civil rights movement, the aims and conduct of the war in general—and the role of the press in particular—remained vexed political questions long after events had run their course. The Vietnam War began as World War II ended and the French tried to re-establish colonialism. US assistance grew as the French lost control of the northern part of the country in the late 1950s. The United States supported a weak regime in the South through the 1960s and, after a series of military defeats, withdrew all forces in 1975.

National reconciliation never really took place following the Vietnam War. Unlike the civil rights movement, the aims and conduct of the war in general—and the role of the press in particular—remained vexed political questions long after events had run their course. The Vietnam War began as World War II ended and the French tried to re-establish colonialism. US assistance grew as the French lost control of the northern part of the country in the late 1950s. The United States supported a weak regime in the South through the 1960s and, after a series of military defeats, withdrew all forces in 1975.

Two major points of controversy included the skepticism of the press corps and the impact of television images on public opinion.

The press corps was skeptical, but the reporters themselves saw it as part of their responsibility. One reporter in particular, World War II veteran reporter Homer Bigart, had never played the role of cheerleader for the home team, even in World War II. As colleague Malcolm Browne said:

However critical his reporting of such military blunders as the Anzio beachhead (in World War II) could be, there was never any doubt which side had his sympathies. In Vietnam, by contrast, Homer could never wholeheartedly identify himself with an American team that often looked arrogant and wrongheaded and whose cause seemed questionable to him. (Browne, 1993)

The later generation of reporters had a different take. David Halberstam initially believed that a US victory was needed to discourage “so-called wars of liberation,” but eventually came to the conclusion that the war “was doomed,” and that the United States was “on the wrong side of history. Neil Sheehan, a UPI reporter, saw the war as being lost on the ground long before it was lost in American public opinion. And studies of US media coverage showed that public opinion against the war was significantly higher than the relatively neutral coverage of the war (Vaughn, 2008).

The role of television in bringing into American homes the horrors of war was also a point of contention long after the war. Although this view would later influence US military censorship policies, network concerns about the sensibilities of their audiences kept gory war footage off the air. For the military, the main lesson of Vietnam was that reporters would need to be managed. Press pools in conflicts ranging from the Falklands (1982), Grenada (1983), Panama (1989), the Iraq conflicts (1991, 2003) and Afghanistan (2000s) were kept away from war’s gruesome scenes and troubling questions about civilian casualties.

- Typical pro-war propaganda

- Cam Ne — Video CBS news

- Accuracy in Media view of the role of press in the Vietnam war

- Robert MacNamara on the role of the press in Vietnam

Cold War

Ted Turner and CNN spent enormous amounts of time and energy on the US – Russian relationship in the 1980s, working on “Friendship Games” and later, an exemplary history of the Cold War co-produced with BBC.

“ . . . Rapid development of satellite television and cell phones . . . helped end communism by bringing in information from the outside. It was possible to get news from independent sources; stations like the BBC (British Broadcasting System) and VOA (Voice of America) were beyond government control. During ‘50s and ‘60s, the Communist government put people accused of listening to these stations in prison . . . It’s hard to believe that things like that actually happened from today’s perspective.” — 2002 interview with Wired magazine, Lech Walesa

“ . . . Rapid development of satellite television and cell phones . . . helped end communism by bringing in information from the outside. It was possible to get news from independent sources; stations like the BBC (British Broadcasting System) and VOA (Voice of America) were beyond government control. During ‘50s and ‘60s, the Communist government put people accused of listening to these stations in prison . . . It’s hard to believe that things like that actually happened from today’s perspective.” — 2002 interview with Wired magazine, Lech Walesa

Middle Eastern wars

Many scholars and press critics insist that the US press failed in its role in the Iraq wars. “Large portions of the (American) public … failed to get accurate messages about what had occurred, which raises compelling questions about the role and practice of the press in a democratic society,” according to a 2003 study by the Program on International Policy Attitudes (PIPA) at the University of Maryland. The survey respondents primary news source was the most important predictor of the frequency of misperceptions. The study found three widespread misperceptions:

- 49 percent believed that the United States had found evidence that Iraq was working closely with al-Qaeda;

- 22 percent believed that actual weapons of mass destruction had been found in Iraq;

- 23 percent believed that world public opinion favored the United States going to war with Iraq.

A fourth misperception — that the Middle East has 2/3 of the world’s oil — was also a factor in the war. (In fact, according to a 2000 USGS report, it has 1/3 of conventional oil and a much smaller fraction of unconventional hydrocarbons.)

— Interview with Danny Schecter, producer of Weapons of Mass Deception

— Danish television video on embedding of journalists with troops

Further reading / current issues

Violence in Mountaintop Removal Mining environmental debate