Civil rights leaders talk with news reporters after meeting with President John F. Kennedy following the March on Washington, D.C. Aug. 28, 1963. That’s Martin Luther King, Jr., to the right of the microphones. Photo by Warren K. Leffler, US News & World Report. (Library of Congress).

One of the most significant moments in the history of the American press involves the ongoing struggle for civil rights in the Black press and the parallel fight in the late 19th and early 20th centuries of the White / mainstream press against civil rights. However, this changed by the 1950s, as the White mainstream press gradually awakened to its responsibilities and began to lead a positive response to the civil rights movement. Special credit for this goes to the Atlanta Journal and the New York Times. But none of that could have occurred without the Black press holding up the standard through the turbulent early years.

There are two stories:

- Part I (on this page) is the story of the African American / Black press — the mainstay of the long movement for equality.

- Part II is the story of the White / mainstream press and its eventual understanding of civil rights.

PART I — The African American press

The greatest single power among African Americans in the 20th century was the press, as three generations of historians have observed. (Roberts & Klibanoff 2006; Myrdal 1942; Edward Sims, 1926). “The negro press was the signal corps,” wrote Margot Lee Shetterly, author of Hidden Figures, “giving the watchword so that the negro community moved forward in synch with America.”

African American newspapers and magazines employed writers like Langston Hughes and Ida B. Wells; they campaigned for integration; they organized boycotts of racist films like the 1915 “Birth of a Nation;” they advocated migration from the South to the industrial North during the 1910 – 1930s era; they covered race riots and investigated lynchings; they debated tactics and helped clarify the goals of the civil rights movement. And, all too frequently, the black press became the prime target for censorship or attacks by savagely prejudiced mobs.

Altogether some 2,700 African American newspapers came to life during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, mostly after the US Civil War, but they survived for only about nine years on average. Despite a lack of financial power, the African American press was the crucible of the ongoing civil rights movement and the main crossroads for public discourse.

It’s important to remember this history, even in the 21st century. When great historical injustices are finally recognized, the stories of resistance take on deep significance.

Origins of the African-American Press

The African American press emerged as part of the abolitionist movement in the early 19th century. Perhaps the first abolitionist newspaper was The Emancipator, initially published in 1819 in Baltimore, Md., and the Genius of Universal Emancipation in the 1821. Both were edited by Benjamin Lundy, a White editor who advocated gradual emancipation. Despite his moderate position, Lundy was nearly beaten to death by a notorious Baltimore slave trader, Andrew Woolfolk, in 1827. The courts convicted Woolfolk but levied the lightest possible fine of one dollar, saying that Lundy provoked it by criticizing Woolfolk’s lawful job trading slaves.

The first newspaper edited by African Americans, Freedom’s Journal, was a response to a New York city hate speech campaign that had started in the early 1820s. Mordecai M. Noah, editor of the New York Enquirer, attacked African Americans daily in his newspaper, for example, assailing their presumed lack of integrity and courage; questioning the chastity of black women; and railing against setting slaves free; and calling free blacks an “abominable nuisance.” These vicious attacks have led historians to label Noah as “the most vile protagonist” in the city, and a “perpetrator of evil” (Washburn, 2006).

“As a result a group of free blacks met in New York and decided that starting a weekly newspaper was the best way to counteract Noah’s anti-black campaign because other avenues of communication were largely closed to them,” said Patrick Washburn, author of The African American Newspaper: Voices of Freedom.

The group elected John Brown Russwurm and Samuel Cornish as the editor and business manager of the new Freedom’s Journal which was first published on March 17, 1827. The editorial policy was to fight slavery and prejudice with low budgets and high expectations. With typical eloquence, Russwurm wrote:

John Brown Russwurm

“Christianity enforces this dictate of sound reason: ‘Thou shalt love they neighbor as thyself,’ (which) is as much the law between master and slave as between any other members of the human family. This is so obvious as to appear almost like a truism. And yet this is the very thing that has always been lost sight of, among slave-holders…. We wish to plead our own cause… ”

Unlike his publishing partner Rev. Samuel Cornish, Russwurm was convinced that African Americans would never be treated as equals in the US. Shortly after Freedom’s Journal stopped publication, he moved to what is now Liberia, on the west coast of Africa, to edit the Liberia Herald and serve as an agent for freed American slaves who returned to Africa.

The abolitionist cause was taken up by Lundy associate William Lloyd Garrison in The Liberator, published from 1831 until 1865. Garrison said in the first issue:

“Assenting to the self-evident truth maintained in the American Declaration of Independence, that all men are created equal, and endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights, among which are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness, I shall strenuously contend for the immediate enfranchisement of our slave population.”

Garrison faced criminal charges in North Carolina for advocating the abolition of slavery, and a South Carolina ‘vigilance’ association offered a reward of $1,500 for information about distributors of the paper.

One of Garrison’s associates was Philip Alexander Bell who in 1837 began publishing the Colored American (1837-1841) with the help of Samuel Cornish. The newspaper provided the best day-to-day coverage of the trial of the mutiny on the Amistad ship in 1839. Bell was also active in the “Underground Railroad” before the Civil War, but in 1860 he moved to San Francisco and began editing the Pacific Appeal, one of the first major black newspapers in California. By 1865, Bell established his own weekly newspaper, The Elevator, under the slogan, “Equality Before the Law,” and especially advocating voting rights for African Americans.

Around 1847, Willis A. Hodges — a Virginia freeman who had to flee the state for New York after the Nat Turner rebellion — approached the editors of the New York Sun and asked for support for a political referendum on state voting rights in New York. The editors refused, saying “The Sun shines for all white men, and not for colored men.” As a result, Hodges and several others created the Ram’s Horn in 1847. The paper was very outspoken in opposing slavery, for example, saying that failure of Northern Blacks to strongly oppose slavery was a “Sambo mistake.” Hodges was also a friend of John Brown, the famed abolitionist who led the raid on Harper’s Ferry in 1859.

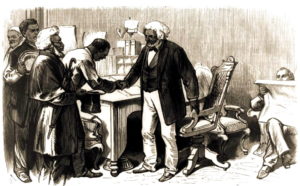

Perhaps the best-known of the African American and abolitionist newspapers before the US Civil War was the North Star, published fromDecember 3, 1847 through the mid-1860s by former slave Frederick Douglass. A fiery orator and passionate writer, Douglass wrote:

“The white man’s happiness cannot be purchased by the black man’s misery. Virtue cannot prevail among the white people, by its destruction among the black people, who form a part of the whole community. It is evident that the white and black must fall or flourish together.”

Censorship by mob, 19th century style

Following the 1822 Denmark Vesey rebellion in Charleston, SC and the 1831 Nat Turner rebellion in Virginia, amendments to the “Slave Codes” made the possession or distribution of abolitionist literature illegal. In Virginia, anyone who “by speaking or writing maintains that owners have no right of property in slaves” could be sentenced to a year in prison. Similar laws were passed across the South.

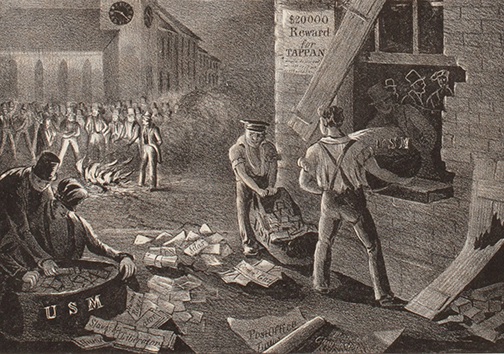

I n the summer of 1835, an abolitionist group began mailing anti-slavery literature to people in South Carolina in what may have been one of the first direct mail political campaigns. Incensed at being exposed to ideas they found dangerous, a Charleston mob broke into the post office, dragged out sacks of antislavery publications and burned them on the street, despite attempts by the Charleston postmaster to hold the mob off with a shotgun.

n the summer of 1835, an abolitionist group began mailing anti-slavery literature to people in South Carolina in what may have been one of the first direct mail political campaigns. Incensed at being exposed to ideas they found dangerous, a Charleston mob broke into the post office, dragged out sacks of antislavery publications and burned them on the street, despite attempts by the Charleston postmaster to hold the mob off with a shotgun.

Tensions kept rising despite efforts of some moderates, such as white Baltimore editor Hezekiah Niles, to find common ground and avert a looming Civil War. Southerners often professed outright hatred of Niles and other opponents of slavery. In fact, it could be very dangerous to publish editorials against slavery in the white or black press. On Nov. 7, 1837, for example, a pro-slavery mob killed abolitionist editor Elijah Lovejoy of the Alton, Illinois, Observer. Lovejoy is often considered the first US martyr to freedom of the press, and his name leads a monument to slain journalists in Washington DC.

The Black Press in the Civil War

Large northern cities had at least one African American newspaper by 1860. These included the National Era of Washington DC, the Christian Recorder of Philadelphia and the Angl0-African of New York.

As the Civil War broke out, one of the largest controversies involved the use of Black troops to fight Southern armies. Although Blacks would not be allowed to join the army for several years, the Christian Recorder asked whether Black soldiers should risk their lives or liberty, given that the Supreme Court had recently held (in the 1857 Dred Scott decision) that African Americans were not citizens, even if they were technically free. On the other hand, the Anglo-African endorsed the idea in an editorial headlined “The Reserve Guard:”

As the Civil War broke out, one of the largest controversies involved the use of Black troops to fight Southern armies. Although Blacks would not be allowed to join the army for several years, the Christian Recorder asked whether Black soldiers should risk their lives or liberty, given that the Supreme Court had recently held (in the 1857 Dred Scott decision) that African Americans were not citizens, even if they were technically free. On the other hand, the Anglo-African endorsed the idea in an editorial headlined “The Reserve Guard:”

Colored men whose fingers tingle to pull the trigger, or clutch the knife aimed at the slaveholders in arms, will not have to wait much longer. Whether the fools attack Washington and succeed or whether they attempt Maryland and fail, there is equal need for calling out the nation’s ‘Reserve Guard.’

Another controversy involved the consequences of emancipation. There were fears that formerly enslaved would “overrun the entire North as the frogs did the Egyptians in the days of Moses,” and that if emancipated “they will refuse to work and will engage in robbery and murder”(McGruder 2014). However, using data from the British experience abolishing slavery in the Caribbean in 1830, the Christian Recorder in a Jan. 4, 1862 article showed that none of these fears were realistic. The newspaper concluded that emancipation was in the national interest, “for it will not only crush rebellion, but increase our prosperity, decrease crime in our midst, and prevent insurrections with their fearful horrors.” These controversies became moot, of course, with the Emancipation Proclamation (Jan. 1, 1863) and the creation regiments of “Colored Troops” in the Union Army (May 22, 1863).

As the Union Army began sending regiments of black soldiers into battle, one black journalist, Thomas Morris Chester, became a correspondent for the Philadelphia Press. He followed regiments of black soldiers into battle, sharing their triumphs and hardships, and always portraying their efforts as heroic — even when they were working as laborers.

Chester had a contempt for Confederates, often calling them “barbaric.” One story is that in April of 1865, when Richmond was liberated by Union troops, Chester went to the statehouse and was writing an article while sitting at the desk of the Speaker of the Confederate House. Suddenly, he was interrupted by a paroled Confederate officer who attempted to throw him out. Chester stopped writing and the former Confederate officer “found himself tumbling over chairs and benches, knocked down by one (of Chester’s) well-planted blow between his eyes” (Huets, 2015)

- Also see: Kevin McGruder, “The Black Press During the Civil War,” NY Times, March 13, 2014

- And Jean Huets, “A Black Correspondent at the Front,” NY Times Feb 8, 2015.

After Union troops captured New Orleans, the first African American daily newspaper, the New Orleans Tribune, debuted on July 21, 1864. The newspaper was founded and financed by Dr. Louis Charles Roudanez, who, like many free people of color in New Orleans, grew up with the French Catholic tradition, and was educated in Paris. The Tribune was instrumental in the creation of the Freedmen’s Aid Association, the local branch of the National Equal Rights League, the Friends of Universal Suffrage, and ultimately, the Louisiana Republican Party. It lasted until about 1870.

Reconstruction era South

After the Civil War, racial and political tensions created widespread violence in the South. A majority of newly freed African Americans strongly supported the Republican Party, angering prominent southern Democrats. The Ku Klux Klan, the White Camelia, the Red Shirts, and other supremacist / terrorist organizations worked to silence African Americans through beatings, assassinations and lynchings.

Aaron Bradley a black Georgia lawyer and politician in the 1860s and 70s, was repeatedly arrested for using “insurrectionary language,” which was no more than asking for reparations and telling former slaves to stay on the land and claim it for themselves. He was sentenced by federal reconstruction authorities in 1865 to a year of hard labor for his speeches, but authorities allowed him to leave the state instead. He returned to Georgia and helped organize Georgia’s Constitutional Convention of 1867, where he championed civil and political rights for African Americans, according to an article by Kerri Lee Merritt. He was also known for filing a lawsuit against B&O railroad because the company insisted that he sit in the “colored” section of the train. But eventually, Bradley left the South and settled in the Midwest, unwilling to endure the constant denial of civil rights and risk death at the hands of angry former Confederates.

Aaron Bradley a black Georgia lawyer and politician in the 1860s and 70s, was repeatedly arrested for using “insurrectionary language,” which was no more than asking for reparations and telling former slaves to stay on the land and claim it for themselves. He was sentenced by federal reconstruction authorities in 1865 to a year of hard labor for his speeches, but authorities allowed him to leave the state instead. He returned to Georgia and helped organize Georgia’s Constitutional Convention of 1867, where he championed civil and political rights for African Americans, according to an article by Kerri Lee Merritt. He was also known for filing a lawsuit against B&O railroad because the company insisted that he sit in the “colored” section of the train. But eventually, Bradley left the South and settled in the Midwest, unwilling to endure the constant denial of civil rights and risk death at the hands of angry former Confederates.

Memphis and New Orleans Riots of 1866 — A year after the war’s end, a community of about 20,000 freed African Americans was attacked by Whites in Memphis, Tenn., leaving 46 dead and 75 injured, and also leaving 91 homes, 4 churches and 8 schools burned to the ground. A similar riot left 44 dead in New Orleans in July of 1866. The outrage over the riots led to a national electoral victory for Republicans, which led to the establishment of military districts and also to the passage of the 14th Amendment to the US Constitution.

The Fourteenth Amendment — Passed July 9, 1868, the 14th Amendment said that all citizens would have equal protection of the laws and that no state had the power to deny rights to any citizen. This rather clear-cut Constitutional amendment would be undermined only a few months later, following the Opelousas massacre of 1868 At least 200 African Americans and 20 whites were killed in Opelousas, Louisiana on September 28, 1868 following a series of editorials in the “The Landry Progress,” a Republican newspaper, urging African Americans to vote for (then liberal) Republicans since the (then conservative) Democrats were oppressing them. Progress editor Emerson Bentley was badly beaten, and his newspaper was destroyed.

The Colfax (La) Massacre of April, 1873 was another an instance of violent repression of legitimately elected officials in Colfax, Louisiana. At least 150 black men were killed — many after they had surrendered to whites. In 1875, the US Supreme Court ruled, in US v Cruickshank, that whites who participated in the massacre could not be convicted under the 14th Amendment designed to guarantee due process and equal rights to all American citizens.

The Danville (Va) Riots of November, 1883, led to the deaths of four black men and pushed the bi-racial reconstruction “Readjuster” party out of office. Like similar riots throughout the South, the point was to curtail black economic and political power. Two years later, a civic booster wrote that the riot produced a change in the behavior of black citizens: “Those who had formerly been most insolent in their conduct now became polite and respectful, ready to yield all reasonable deference to their natural superiors, and to resume, contentedly, their own legitimate position in the social scale.” (Brendan Wolff, 2017) It also pushed moderate legislators like William Mahone, a former Confederate general, out of office in Virginia.

Expansion of the black press in the 1880s

The black press expanded quickly in the 1880s and early 1890s, from 31 newspapers to 154, according to a very optimistic 1891 book, The Afro-American Press and its Editors, by Irvine Garland Penn, a leading black writer and educator. This was the high water mark of the post-Civil War black press. Few of the Southern newspapers would survive to the turn of the century.

John Mitchell Jr., Editor, The Richmond (Va) Planet, 1884 – 1925

John Mitchell Jr. and the Richmond Planet

One of the most astonishing stories is that of John Mitchell, Jr., of the Richmond Planet from 1884 – 1925. A resident of Richmond, Va.’s Jackson Ward area, Mitchell was born into slavery in 1863, but his family was freed when Union troops captured the city in April 1865. When the Richmond Planet was established in December, 1884, Mitchell was chosen as its editor. He began reporting on injustice and lynchings right away, and often received death threats. He reported on a lynching in Smithville, Charlotte county, Virginia in May, 1886. Afterwards, someone sent Mitchell a rope with a note attached to it, warning that he would also be lynched if he ever set foot in Smithville. He responded with a line from Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar:

“There are no terrors, Cassius, in your threats, for I am so strong in honesty that they pass by me like the idle wind, which I respect not.”

Afterwards, armed with two Smith & Wesson pistols, Mitchell took a train to Smithville and walked five miles from the station to see the site of the hanging. (Duke, 1983)

Covering another lynching in 1898, Mitchell wrote this headline: “They Lynched Him; A Colored Man Dealt With – Taken From the Train; Died Protesting Innocence; A Brutal Murder – Mob Makes No Effort At Disguise.”

Mitchell also opposed the construction of confederate memorial statues along Richmond’s Monument Avenue, predicting that the monument “will ultimately result in handing down to generations unborn a legacy of treason and blood.”

The fact that Mitchell survived as an editor in Richmond for 40 years was unusual. Many writers, such as Ida B. Wells, could not remain in the South, and the success of most of the black press was short-lived after the Reconstruction era gave way to the “Jim Crow” era of severe, violent repression, the wide extent of which is still unknown and unacknowledged.

American courts did not support basic rights or even common safety for African Americans in the post Civil War era. The US Supreme Court upheld “Jim Crow” laws in the Slaughterhouse (1873) and Cruickshank (1876) cases. As a result, state laws that denied African Americans equal protection and civil rights in dozens of areas, from seating on busses and trains to service at lunch counters and even to the way people walked down the street, were upheld as constitutional.

Puck magazine Sept. 9, 1908, depicts “Lawlessness” instead of Liberty. The comment may be closer to the truth than was known at the time. The original Statue of Liberty design is linked to America’s liberation of enslaved African Americans after the Civil War, but how deeply linked is a subject of some debate.

The original Statue of Liberty

In 1865, a French political intellectual and anti-slavery activist named Edouard de Laboulaye proposed that a statue representing liberty be built for the United States. The original design featured a woman holding the torch of freedom in one hand and broken chains (not a tablet) in the other.

The substitution of the chains with a tablet is confirmed, but a controversial assertion is that the model of the woman holding the torch was originally African due to Laboulave’s desire to celebrate emancipation after the US Civil War. This is disputed, according to September, 2000, National Park Service report.

We do know that French sculptor Auguste Bartholdi was selected to bring Laboulaye’s idea forward, and in 1870, he began designing the statue of “Liberty Enlightening the World.” And we also know that the original design was changed at some point. According to one author (Yasmin Sabina Kahn), Bartholdi did originally design Liberty holding a broken chain.

“Bartholdi’s original depiction of Lady Liberty had her holding broken chains in her left hand, with more broken chains and broken shackles at her feet. The chains were symbolic of the end of slavery in the United States,” Khan said. However, Bartholdi’s financial backers in the US “decided this would be too divisive in the days after the Civil War.”

But what about the original design being linked to slavery? “In addition to his abolition work, Laboulaye was also a U.S. Constitution expert,” said Sharon Kyle in an L.A. Progressive article. “Although we cannot know this for sure, one can only imagine that the 1865 signing of the 13th amendment to the U.S. Constitution would be very important to an abolitionist and likely fueled Laboulaye’s desire to have the monument built.”

According to another National Park Service article, the best-recognized symbol of liberty on earth gave little comfort to African Americans, who were (by some accounts) the very people it was originally supposed to depict:

After the Statue’s dedication in 1886, the Black Press began to debunk romantic notions of the Statue of Liberty and American History. Racism and discrimination towards African Americans did not end after the Civil War or with the dedication of the Statue – it continued on for more than a century. As a result, the Statue was not a symbol of democratic government or Enlightenment ideals for African Americans but rather a source of pain. Instead of representing freedom and justice for all, the Statue emphasized the bitter ironies of America’s professed identity as a just and free society for all people regardless of race. From the time of the Statue’s dedication, attitudes towards the Statue in the African American community were ambivalent and uncertain.

W.E.B. Du Bois wrote … that he was unable to imagine the same sense of hope he assumed some immigrant arrivals had felt when he sailed past the Statue on a return trip from Europe. This hope did not pertain to his race. The fight for equality, liberty, and justice for all at this point in time had not been achieved, but rather disregarded after the Statue’s completion and dedication. Therefore, African Americans rarely used the Statue as a relevant symbol for their struggle – they were reluctant to embrace the symbol of a nation which would not fully include them as citizens. The Statue of Liberty did not help them to gain equality and justice in the truest sense – it was only the beginning.

Nikki Giovanni spoke about her search for the hidden truth about the Statue of Liberty. “The chains are still there, but they are hidden, at her feet,” Giovanni said in 2018.

The Crusader: One major opponent of Jim Crow law was The Crusader, a New Orleans newspaper founded in 1889 by attorney Louis Martinet. His idea, according to historian Keith W. Medley, was to combat the increasingly virulent racism of other New Orleans papers. The Crusader was intended to be “spicy, progressive, liberal, stalwart, fearless,” and to stand for “A Free Vote and Fair Count, Free Schools, Fair Wages, Justice and Equal rights.”

Martinet and others organized a committee (Comité) to fight the Jim Crow car law, raising about $3,000 to launch two test cases: one to challenge the legal segregation of trains on interstate routes and one to challenge segregation on conveyances within the state. The aim: to “seek redemption” from the Supreme Court of the United States. “We find this the only means left to us,” a Comité statement concluded. “We must have recourse to it, or sink into a state of helpless inferiority.”

The Supreme Court endorsed that helpless inferiority in the Plessy v Ferguson case of 1896, which allowed supposedly “separate but equal” facilities for whites on the one hand and people of color on the other. The Crusader stopped publishing in 1898.

These and similar court cases are the backdrop against which freedom of the press and other human rights would be denied to African-Americans in the 19th and 20th centuries. Not until 1954, with the Brown v. Board of Education case, was the “Separate but Equal” doctrine overturned.

With law enforcement free to ignore gross injustices, black communities came under vicious attack by white mobs intent on holding down the rising economic and political power of African Americans. These attacks often focused on the newspaper as the center of the community, as was the case in Memphis, TN, and Wilmington, NC, in the 1890s.

Suppression of the black press in the 1890s

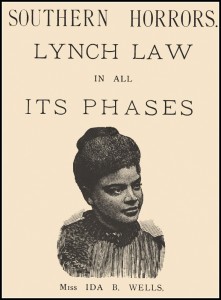

In 1892, a black journalist named Ida B . Wells (July 16, 1862 – March 25, 1931) investigated a lynch mob in Memphis, TN. She wrote that the three men who had been hung were innocent, and that the real motive for the lynching was to put a prosperous grocery store out of business. As a result, her newspaper, The Free Speech, was burned to the ground. Much of this was described in her book “Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All its Phases.

“The dailies and associated press reports heralded these [lynched African Americans] … as “toughs,” and “Negro desperadoes who kept a low dive.” … Not content with misrepresenting the race, the mob-spirit was not to be satisfied until the [African American Free Speech newspaper] …, which was doing all it could to counteract this impression, was silenced. The colored people were resenting their bad treatment in a way to make itself felt, yet gave the mob no excuse for further murder, until the appearance of the editorial which is construed as a reflection on the “honor” of the Southern white women. It is not half so libelous as that of the [Memphis] Commercial [newspaper] which appeared four days before, and which has been given in these pages.

“The dailies and associated press reports heralded these [lynched African Americans] … as “toughs,” and “Negro desperadoes who kept a low dive.” … Not content with misrepresenting the race, the mob-spirit was not to be satisfied until the [African American Free Speech newspaper] …, which was doing all it could to counteract this impression, was silenced. The colored people were resenting their bad treatment in a way to make itself felt, yet gave the mob no excuse for further murder, until the appearance of the editorial which is construed as a reflection on the “honor” of the Southern white women. It is not half so libelous as that of the [Memphis] Commercial [newspaper] which appeared four days before, and which has been given in these pages.

They would have lynched the manager of the Free Speech for exercising the right of free speech if they had found him as quickly as they would have hung a rapist, and glad of the excuse to do so. The owners were ordered not to return, the Free Speech was suspended with as little compunction as the business of the “People’s Grocery” broken up and the proprietors murdered.

Wells moved to New York City, where she helped found the NAACP, wrote for its publication The Crisis, and was active in politics for the rest of her life. One important episode (mentioned below) is her investigation of the 1917 East St. Louis riots.

The Wilmington NC insurrection of 1898

A jubilant mob of white vigilantes poses before the ruins of an African American newspaper, the Daily Record, of Wilmington, NC. destroyed on November, 10, 1898.

Following the election of a pro-tolerance (Fusion) city government, made up of progressive whites and African Americans, a mob of 2,000 white men staged a coup, displacing the city government and destroying the only African American newspaper in North Carolina, the Wilmington Daily Record. State and federal troops — originally sent to quell rioting — ended up joining the rioters and firing on unarmed African Americans. Rioting continued for several days, unhindered (and sometimes encouraged) by local law enforcement. At least 60 were killed, and thousands of African Americans — including employees of the Daily Record — left North Carolina to escape oppression. John Mitchell of the Daily Planet in Richmond, Va. headlined his Nov. 19, 1898 story: “Horrible Butcheries at Wilmington.”

Gonzales murder, Columbia, SC, 1903

To give an idea of the absolute impunity with which race haters operated, consider the case of the first Hispanic American journalist to be killed in the line of duty. Narciso Gonzales was headed home from his job at The State newspaper in Columbia, South Carolina on Jan. 15, 1903, when he was shot by then-Lt. Gov. James Tillman. Gonzales had opposed Tillman’s unsuccessful candidacy for governor and had called him a “debaucher,” “blackguard” and a “proved liar.” Tillman was tried for the murder and acquitted, although he was carrying two loaded weapons, and the victim was unarmed.

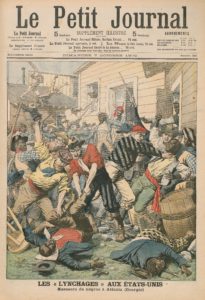

News of the Atlanta riot was quickly carried around the world. The Petit Journal of Paris depicted the riot on its cover Oct. 7, 1906

Atlanta riot, 1906 — At least 25 and as many as 100 African Americans were murdered by rampaging white men in Atlanta, Ga. between Sept 22 and 24 in 1906. Some were hanged from lamp posts; others were shot, beaten or stabbed to death. Perfectly innocent people were pulled into the street and attacked as white mobs invaded black neighborhoods and business areas.

Ray Stannard Baker, a famous white muckraker, covered the Atlanta riots in his book: Following the Color Line: An Account of Negro Citizenship in the American Democracy. He wrote the book “without excuse for the horror of the details,” he said in its introduction.

According to Baker, the white news media played a large part in accelerating racial animosity:

“Certain newspapers in Atlanta, taking advantage of popular feeling, kept the race issue constantly agitated, emphasizing Negro crimes with startling headlines. One newspaper even recommended the formation of organizations of citizens in imitation of the Ku Klux movement of reconstruction days. In the clamor of this growing agitation, the voice of the right-minded white people and industrious, self-respecting Negroes was almost unheard. A few ministers of both races saw the impending storm and sounded a warning—to no effect… “

Baker focused on the Atlanta riot, mentioning a few others, and took pains to explain that lynchings and riots were just as criminal as the supposed crimes committed by African Americans that sparked the riots. But even in a long and complex work like The Color Line, Baker did not rise above the prejudices of his time, taking a condescending tone and, for example, only mentioning other riots in passing, such as the 1898 massacre. Baker interviewed Wilmington Daily Record editor A.L. Manley, who “was driven out and his property was destroyed.” Baker made no other reference to the massacre.

Lynchings become common

As repression followed repression, the lynchings reported by John Mitchell Jr., Ida B. Wells and Ray Stannard Baker were becoming increasingly common.

According to James Allen in Without Sanctuary, the Tuskegee Institute recorded the lynching of 4,742 people between 1882 and 1968. “This is probably a small percentage of these murders, which were seldom reported, and led to the creation of the NAACP in 1909,” Allen said. “Through all this terror and carnage, someone – many times a professional photographer – carried a camera and took pictures of the events… These images are some of photography’s most brutal, surviving to this day so that we may now look back upon the carnage and perhaps know our history and ourselves better.”

Often enough, black reporters working for the black press had the heartbreaking job of bearing witness to lynchings, said Roger Witherspoon, a black editor and author of Martin Luther King, Jr.: To The Mountaintop (Doubleday, 1985). “The hard part was staying long enough to record most of the horrors and bear witness to the atrocities, and leaving before the crowd’s blood lust added the reporters to the flames. Leaving was difficult. They could only hope that the victim was too far gone or blinded (gouging the eyes out or burning them out was a favorite) to notice that they were, truly, alone.”

A Pittsburgh, PA attorney, Vann helped found the Pittsburgh Courier, an important African American publication. This WWII-era government illustration was meant to remind African Americans that their contributions were valued, despite continued discrimination. Illustration by Charles Henry Alston, Office of War Information, 1943, US National Archives.

Progressive era and the Black press

Not surprisingly, with all the repression in the South, large percentages of African Americans migrated to northern states.

“Millions heeded (the) call to leave the Klan terror and pseudo-slavery of the South behind for freedom and opportunity up North,” said Larry Muhammad in a 2003 Nieman Reports article.

This “great migration” to the north was led, in part, by the Chicago Defender, first published in 1905 by Robert S. Abbott, and also by the Pittsburgh Courier, founded in 1910 Edward Nathaniel Harleston. Also in 1910, W.E.B. Du Bois became the founding editor of the NAACP magazine, The Crisis.

Another great migration to the west was also under way, and The California Owl started up in Los Angeles in 1879 to inform them about jobs, housing and other information. It was started by John James Neimore and evolved into one of the leading papers of the day when Charlotta A. Bass (nee Spears) and her husband, John Bass were editors. Charlotta Bass became editor in 1912 after John Bass died, and renamed it The California Eagle.

The early 20th century was a time of a remarkable transformation in the black press, Fred Carroll wrote in his book Race News: Black Journalists and the Fight for Racial Justice in the 20th Century (University of Illinois, 2017). “A skeletal national communications network of news [that was] by, about and for African Americans solidified in the early 1900s… Upstart editors competed for readers pennies and nickels by adopting modern journalism practices and emboldening their demands for justice. These editors condemned lynching, denounced segregation, and defended citizenship rights with an audacious militancy.”

The most important controversy within the black press at this time involved the philosophy of Booker T. Washington on the one hand, who advocated education, gradual equality and accommodation with white supremacists, and W.E.B. Du Bois and members of the Niagara Movement on the other hand, who took a much stronger stand against discrimination and segregation.

In rural America such fine distinctions barely mattered, as raw hatred broke out on the pages of newspapers and then spilled out onto the streets of small towns.

On July 29, 1910, for example, forty to two hundred African Americans were massacred in Slocum, Texas and the rest of the black community was driven out of the county. The Slocum Massacre began with minor incidents but was fanned into White outrage by fabricated newspaper reports about armed African Americans. White men reacted to the imagined threat by driving through black communities and shooting down unarmed Black people. Forty to two hundred were killed. Local and national newspapers, including the New York Tribune said the conflict was started by African Americans or race riots. Other White newspapers condemned the killings. The New York Times wrote that “Score of Negroes Killed by Whites” and described a sheriff as saying they were “shot like sheep.” The Washington Post compared the massacre to pogroms of Jewish communities in Russia.

World War I and the Roaring Twenties

Growing tensions between white and black Americans accelerated after the US entered World War I in April, 1917. The East St. Louis riots in July, followed by the Houston riot in November, alarmed government officials who were preoccupied with the war in Europe.

Riot victims appeal to President Woodrow Wilson, asking that St. Louis be “made safe for democracy.” New York Evening Mail, July, 1917. In response to the riots, 10,000 people marched in New York city.

The East St. Louis riots of July, 1917 involved attacks on the black community after black workers replaced white workers in local factories. At least 40 African Americans were killed and 6,000 homes destroyed. Investigative reporter Ida B. Wells found that community leaders had been asking the governor for protection months beforehand, and that city police and state militia participated in the riots and helped suppress black workers. When her report was published as a pamphlet, the military censored it. When a St. Louis editor linked draft resistance to President Woodrow Wilson’s silence about the riots, the newspaper was banned by the US Post Office.

The Houston riots of November, 1917 were a reaction to what has been called “rampant and prolonged” abuse of black soldiers by white citizens. On Nov. 1, a group of 156 black soldiers from the 24th Infantry Regiment marched on Houston, Texas to fight with police. Four soldiers and 16 civilians were killed. Within a few months, 19 of the soldiers were hung for mutiny and 41 were sentenced to life in jail.

Defending the rioters in the press was also a crime: G. W. Bouldin, editor of the San Antonio Inquirer, printed a letter that said the soldiers in Houston were merely standing up for African American women, and they had every right to fight back. Bouldin was convicted under the Espionage Act and sentenced to two years in prison. (Carroll, 2017).

The growing power of the African American press, coupled with increasing criticism of discrimination and brutality, alarmed government officials during World War I. At a meeting with a group of 30 African American publishers in Washington in June, 1918, then Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D Roosevelt and other officials asked the publishers for loyalty. The publishers said loyalty was not the problem. Lynchings and discrimination were the real problems, they said.

The head of military intelligence sent a memo after the meeting: “The leaders of the race are intensely loyal, but feel keenly their inability to carry the great mass of their race with them in active support of the war unless certain grievances receive immediate attention.” (Carroll, 2017). Around this time Du Bois called for a temporary halt to racial agitation, saying: “If this is OUR country, then this is OUR war.”

Ralph W. Tyler, the first accredited African-American correspondent in World War I.

Later that summer of 1918, small concessions were evident. Ralph Waldo Tyler, editor of the Cleveland Advocate, was accredited to report about black American troops from France. Death sentences for ten of the soldiers who participated in the Houston riots were commuted to life in prison. Black nurses were welcomed into the Red Cross by order of the Army. And in July of 1918, Wilson finally broke his silence on lynching, comparing the victimization of the innocent to activities of the Germans.

These compromises “allowed black editors to claim their efforts had gained a measure of recognition for black concerns unseen at the federal level since Reconstruction ended,” wrote historian Fred Carroll.

White newspapers encouraged riots

White mainstream newspapers encouraged racism and white anger in the post – WWI era.

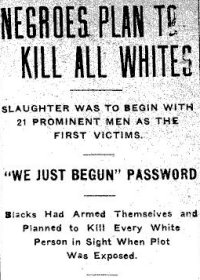

One incident in Elaine, Arkansas illustrates the point: When a group of cotton sharecroppers attempted to assert their rights and unionize in Elaine in 1919, a group of white vigilantes began attacking them. And when they tried to defend themselves, the massacre escalated, and at least 237 were killed.

In the aftermath, the Arkansas Gazette claiming the African Americans were the ones plotting to “kill all whites.” And yet, there was no official investigation of any events surrounding the Elaine Massacre. Only the NAACP sent out an investigator, and the man barely escaped Arkansas with his life.

Tulsa race massacre: Rising tensions in Tulsa, Oklahoma led to riots on May 31-June 1, 1921, that left an estimated 150 – 300 dead, a 40 block area burned to the ground, and many thousands homeless. The Tulsa World newspaper helped created a hostile atmosphere with regular articles about the Ku Klux Klan and the failure of the police to stop black prostitution.

A few days before the riots broke out, the World escalated the hatred. According to the 2001 Tulsa race commission:

In a lengthy, front-page article concerning the ongoing investigation of the police department, not only did racial issues suddenly come to the foreground, but more importantly, they did so in a manner that featured the highly explosive subject of relations between black men and white women. Commenting on the city’s rampant prostitution industry, a former judge flatly told the investigators that black men were at the root of the problem. ‘We’ve got to get to the hotels,’ he said, ‘We’ve got to kick out the Negro pimps if we want to stop this vice.’”

The firestorm of white fury destroyed one of the most vibrant black communities in the nation, once known as “Black Wall Street.” The community never recovered.

The chain of riots and lynchings resulted in increasing radicalization for African Americans and for their press, as new and more radical editors appeared in the 1920s and 30s, such as Marcus Garvey who led a movement that published the Negro World, and Cyril Briggs, editor of the Crusader, a New York based communist publication.

Radical publications had an important influence, but the mainstream black press ended up with the most circulation. By 1929, The Pittsburg Courier had a circulation of 300,000 weekly with 15 editions published around the country. The Chicago Defender‘s circulation reached 230,000 a week. It was this newly empowered press that threw its weight behind the Democratic Party in the 1932 election, breaking traditional ties to the Republican Party of Abraham Lincoln and helping to elect Franklin D. Roosevelt to the presidency.

The Great Depression of the 1930s led to the downfall of other Black Wall Streets as well. For example, in Detroit, Mich., White bankers demanded full repayment of loans to Black businesses, including the Detroit Defender (a newspaper no longer found in library collections). When the businesses couldn’t pay, the banks foreclosed.

Cinema and race

Motion pictures emerged as a prominent source of entertainment and culture in the early 20th century, and the prejudices of the times are rather obviously reflected in the choice of subjects and the depictions of characters. Uncle Tom’s Cabin, one of America’s most popular books in the 1850s, was made into one of the earliest silent movies in 1903 by film pioneer Edwin S. Porter. In this, like many other depictions of the book, the point was to showcase slave dances and the drama of escape. The meaning of the original book, which involved the torment and pain that slavery caused, was often lost in these dramatizations.

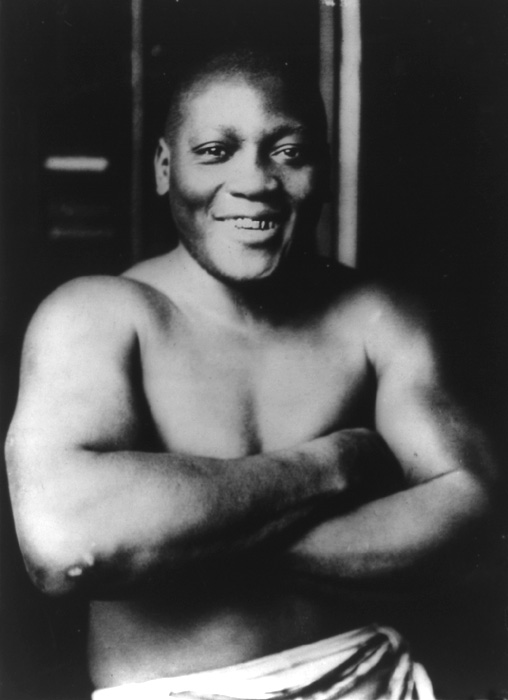

Jack Johnson, boxer, 1910

One ugly episode was a 1910 case of outright film censorship. When the first African- American heavyweight boxing champion, Jack Johnson, won a well-publicized July 1910 match against James Jeffries (a white boxer who had been styled as the “great white hope”), rioting broke out in 50 US cities and an estimated 20 people were killed. The film’s ideological significance alarmed racists in Congress who passed a federal ban on interstate sales of all boxing films in 1912. The ban was later lifted, and the 1938 fight between Joe Lewis of the US and Max Schmeling of Germany was broadcast by radio and widely shown in newsreels as a point of pride for Americans. But states took up censorship duties in the 1920s, and films by people like Oscar Micheaux were banned or drastically altered to elevate racial sterotypes.

It’s no exaggeration to say that virulent, outright racism was a common feature of film in its early years. “Early depictions of African American men and women were confined to demeaning stereotypical images of people of color. During the first decades of the 20th century, many films depicted a nostalgic and idealized vision of life in the antebellum South,” said historians at the Duke University Libraries.

Birth of a Nation, 1915: The Klan captures a renegade named Gus, who pursued a white woman. The Klan lynches him after she commits suicide.

Perhaps the most blatantly prejudiced example is “Birth of a Nation,” a silent film released in 1915. Aside from a few scenes involving American history, nearly all of the movie’s plot followed a book called The Clansmen that romanticized slavery-era antebellum South and the American terrorist group, the Ku Klux Klan. It depicted Reconstruction-era African Americans in the worst possible light as drunkards, rapists and murderers. Critics were outraged, some saying the film was “unfair and vicious.” Riots broke out at theaters in major cities, and performances were shut down in eight states. Many other performances were picketed by the National Association for Colored People. Outside the theater, riots and lynchings often followed showings, and the NAACP attempted, unsuccessfully, to have it banned.

To counterbalance the lurid stereotypes in Birth of a Nation, African-American entrepreneurs ventured into film making to serve some 400 black movie theaters. Filmmakers like Oscar Micheaux of the Lincoln Motion Picture Company who made The Homesteader (1919), and Noble Johnson, who made The Realization of a Negro’s Ambition (1916), were among those who worked in the “separate cinema” until the 1930s, when Depression era economics put most of them out of business. However, state film boards made Micheaux’s work difficult, and several of his films were banned in the South.

The 1939 film “Gone with the Wind” is worth mentioning, since the popular film portrayed vigilantes in a positive light and stereotyped African Americans. The film never mentioned the Ku Klux Klan by name, and even the stereotypes seem to have more human, rounded characters. Hattie McDaniel, who played “Mammie,” won an Oscar as best supporting actress — something that would never have happened in 1915.

And so, changes in American media slowly began to reflect changes in American culture. Where renegade villains and stereotypical buffoons were the only possible depictions of black Americans until the late 1930s and early 1940s, more dignified and talented actors like Bill Bojangles Robinson, Lena Horne, Cab Calloway and the Nicholas Brothers were slowly brought into major Hollywood productions. Unfortunately, Robinson and the Nicholas Brothers dance numbers were often ‘cut out’ of movies by theater chains serving theaters in the South at the behest of state film boards.

Efforts to truthfully depict the humanity of African Americans did, eventually, take root in Hollywood, for example in films like Island in the Sun (1957), To Kill a Mockingbird (1962), Lilies of the Field (1963), Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967), and Blazing Saddles (1974) among others. Even Jack Johnson’s story finally came to cinema in 1970 in The Great White Hope, starring James Earl Jones and Jane Alexander. (See the documentary “Small Steps, Big Strides: The Black Experience in Hollywood.” )

WWII era: Double V and censorship

On Jan. 31, 1942, with America at war for less than two months, James G. Thompson wrote a letter to the editor of the Pittsburg Courier that struck a deep chord. “Should I sacrifice to live half-American?” he asked.

I suggest that while we keep defense and victory in the forefront that we don’t lose sight of our fight for democracy at home. The V for victory sign is being displayed prominently in all so-called democratic countries which are fighting for victory over aggression, slavery and tyranny. If this V sign means that to those now engaged in this great conflict then let we colored Americans adopt the double VV for a double victory.

The “Double V” campaign caught on, and is widely remembered as a reflection of the dilemma faced by African Americans at the time.

Throughout the war, African American soldiers in the US armed forces needed information from home, and black newspapers like the Pittsburgh Courier and the Chicago Defender found large audiences on military bases. That made some white officers uncomfortable.

Around 1943, according to Patrick S. Washburn in The African American Newspaper: Voice of Freedom (Northwestern University Press, 2006), Army bases began confiscating and suppressing black newspapers as “prejudicial to military discipline.” The decision was greeted with anger. The policy was reversed by the Navy late in the war, with this explanation in a 1945 memo:

“It is true that Negro publications are vigorous and sometimes unfair in their protests against discrimination, but it is also true that they eagerly print all they can get about the successful participation of the Negro in the war… Censorship and repression of such interests is not in the American tradition. It cannot be made effective, and has the reverse effect of increasing tension and lowering morale.”

Although the armed forces were segregated in WWII, black American soldiers and sailors made significant contributions in fighting units like the Tuskegee Airmen and the Third Army’s 761st tank battalion — the Black Panthers. The tankers took a 50 percent casualty rate and fought through to liberate the Buchenwald and Dachau death camps, but very little recognition came their way. “The U.S. Army forgot to remember,” said Bill Alexander of BET.com.

Alexander also noted:

John H. Johnson

“The recollections are still vivid – Black soldiers of the Third Army, tall and strong, crying like babies, carrying the emaciated bodies of the liberated prisoners,” wrote Benjamin Bender, a Buchenwald survivor. Another Holocaust survivor, David Yeager of Poland, said of the 761st, “I thought they had come down from heaven.”

It was only decades later that the public learned of these and other heroic instances, even though many were covered in the black press.

In the post-war years, the American press expanded, and an important milestone for the African American press was the establishment of Ebony magazine in 1945 by John H. Johnson. Designed to look like other glossy magazines, Ebony emphasized entertainment and the success of African Americans, but also covered difficult issues of racism and segregation. The success of these and other publications gave a voice to millions of people who were not usually heard in the mainstream media.

In the post-war years, the American press expanded, and an important milestone for the African American press was the establishment of Ebony magazine in 1945 by John H. Johnson. Designed to look like other glossy magazines, Ebony emphasized entertainment and the success of African Americans, but also covered difficult issues of racism and segregation. The success of these and other publications gave a voice to millions of people who were not usually heard in the mainstream media.

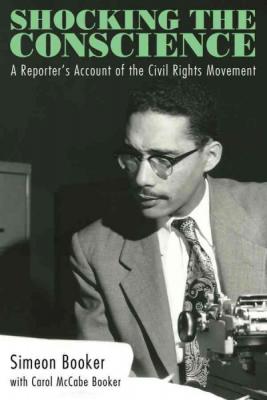

Among the new voices was Simeon Booker, the first black journalist at the Washington Post and regular correspondent for Jet and Ebony magazines, started as a reporter in 1955 and vowed that lynchings would no longer be ignored beyond the black press. He was determined to cover the next murder like none before, and noticed small item on the AP wire reported that a Chicago boy vacationing in Mississippi was missing. Booker was on it, and stayed on it, through one of the most infamous murder trials in U.S. history. His coverage of Emmett Till’s death lit a fire that would galvanize the civil rights movement

John Henry McCray was another of these new voices. In 1939 he began editing the merged Charleston S.C. Lighthouse and the Sumter Informer. It was then the state’s only black-owned newspaper, and during the next 15 years, it became “the voice of black South Carolina” and of the state’s growing civil rights movement. One incident shows the difficulties faced by black journalists at the time. In 1949, McCray interviewed a black man on the eve of his execution. He had been convicted of the sexual assault of a white woman, but he insisted that he was innocent and that his relationship with the woman had been consensual. Under South Carolina law at the time, publishing such information constituted criminal libel, and McCray was fined $5,000 and sentenced to two months at hard labor. according to a New York Times article. The Lighthouse and Informer folded due to financial difficulties in 1954. (For more information see the S.C. state archive and a story in the Charleston Post Courier).

L. Alex Wilson was another of the new voices who suffered for civil rights. He was beaten by a white mob for covering the Little Rock Arkansas integration riots on Sept. 23, 1957, for the Tri-State Defender of Memphis. “Any news man worth his salt is dedicated to the proposition that it is his responsibility to report the news factually under favorable and unfavorable conditions,” Wilson said. “I strive to serve in the category.” Wilson died at a young age, probably from his injuries, but not before he hired Dorothy Gilliam, who went on to work at the Washington Post. Her book about reporting the civil rights era was published in 2019.

The end of an era

As African Americans joined the national mainstream in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, specialized publications like Ebony and Jet became less and less relevant. Johnson publications filed for bankruptcy in April, 2019 and the Chicago Defender went out of print in July, 2019.

But if the expectation was that the mainstream press would now serve both Black and White communities, the reality, in the wave of protests during the summer of 202o, was a White conservative backlash against the press along with the ongoing movement to provide equal rights to all citizens.

Please See Part II of Civil Rights and the Press