It’s six in the morning on November 29, 1814, and London’s Fleet Street is beginning to fill with the cacophony of commerce. But the rows of hand-pulled presses at the London Times, hardly changed since Gutenberg, have for once stopped their creaking and rumbling. The printers have been standing idle, and they are wondering how the newspaper will be produced today. They were told to wait for important foreign news to arrive. Then at dawn, London Times owner John Walter II, a thin man with a beak-like nose, bursts into the pressroom and calls for the printers put down their tools and gather around. He is holding up this morning’s issue of the London Times — the same newspaper they had expected to be producing. Fearful glances are exchanged around the room.

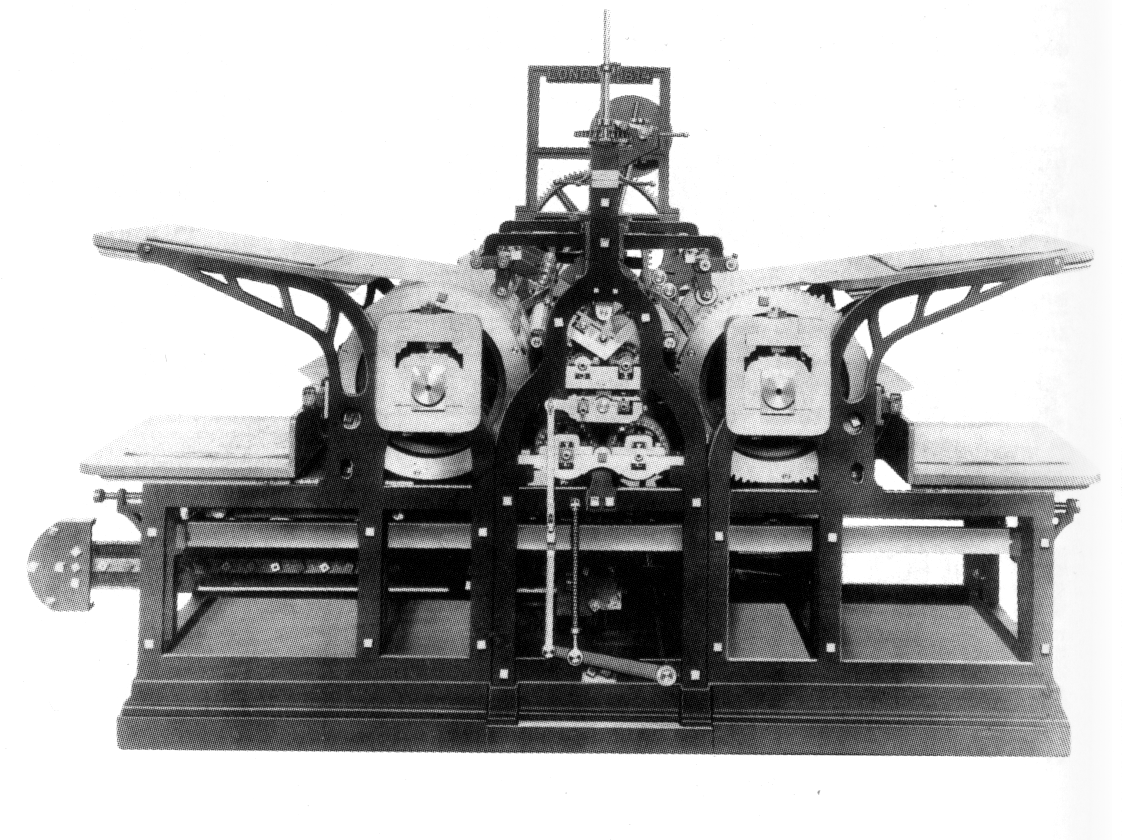

“The Times is already printed — by steam” he announces grandly. He passes the newspaper out to the printers, who regard the boss with anger and suspicion as he explains. Today’s London Times has been printed on a new kind of steam powered press designed by Friedrich Koenig, a mechanical engineer, he tells them. It was built in secret by Koenig’s men in a guarded warehouse down the street.

It’s a tense moment. Workers all over England have been losing their jobs to steam power. Three years before, thousands of jobless textile workers rioted across England’s industrial north. These “Luddite” riots were a reaction to the extreme poverty that suddenly engulfed working families. Fifteen men were hung in York, and more eight in Lancashire, for sabotaging the textile mills.

Walter warns the printers to avoid any Luddite style rebellions in his shop. But he also says that, unlike the textile industry, the London Times will stand by its workers. There will be no layoffs. In fact, the faster press will mean more work for everyone.

The advantage of a steam press is not just speed, he emphasizes, but also less physical labor. This is an important point for the pressmen. Pulling that press lever hour after hour, day after day, is so arduous that it leaves many men with one-sided muscle development. In fact, it’s possible to tell an experienced pressman just from the loping way he walks.

Speed is also important for the business, Walter says. Where a crew of three men on a hand press might print 250 pages per hour, on one side, a crew of six men on the new steam press could produce 1,100 pages, on both sides, per hour — nearly four times the efficiency. (By 1828 it will be 4,000 pages per hour).

And so, by investing in new technology, and treating its workers with respect, the Times of London scores a worldwide first.

The revolution from handcrafted printing to industrial printing production is momentous — Costs of production come down, and due to mass circulation, the potential for advertising support goes up. The significance of the moment is difficult to overstate, but the London Times calls the “greatest improvement” since printing was invented:

“Our journal of this day presents to the public the practical result of the greatest improvement connected with printing, since the discovery of the art itself. The reader of this paragraph now holds in his hand one of the many thousand impressions of the Times newspaper which were taken off last night be a mechanical apparatus. (London Times, Nov. 29, 1814, page 3)

Until the this moment, books and news publications tended to be fairly expensive and oriented towards the elite. But the new steam powered press allowed the mass media to enter an industrial phase. With many more readers, advertisers found they could reach more customers, and the cost of printing a newspaper came down even more. The effect was to free the press from financial dependence on political parties and, with the rapid spread of information, to democratize politics.

See also:

Robert Hoe’s Short History of the Printing Press, 1902. (Full text Google Books) .