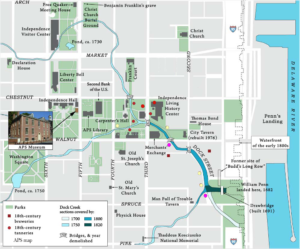

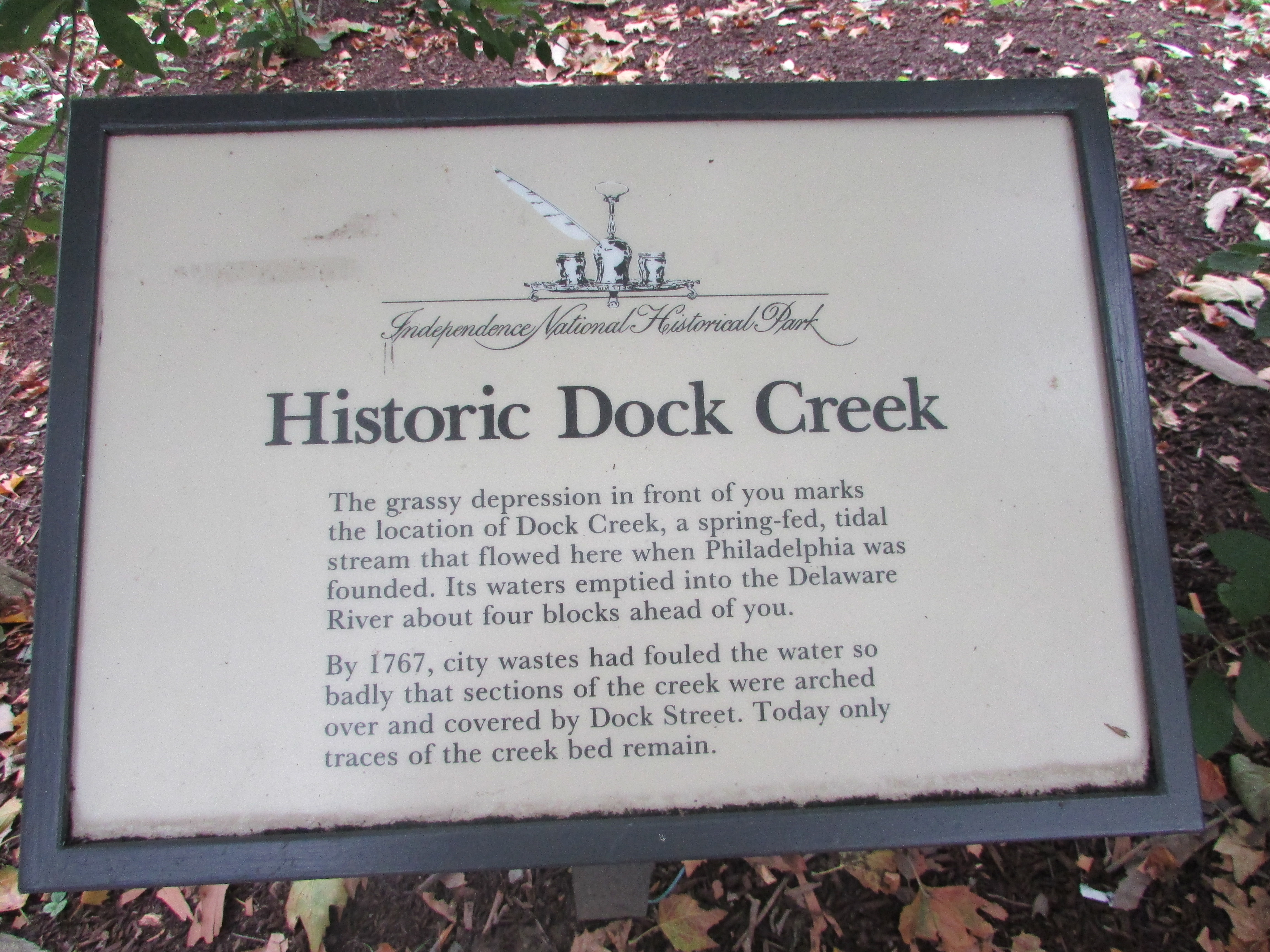

Only a stone’s throw away from Independence Hall, a small brick bridge crosses what was once a thriving waterway in the center of Philadelphia. The waterway was at the center of America’s first environmental controversy covered by two different newspapers in the summer of 1739.

Andrew Bradford’s American Weekly Mercury argued that tanners, brewers and slaughterhouse owners should be free to dump their waste into the creek without regulation.

Benjamin Franklin’s Pennsylvania Gazette argued for “public rights” and regulation of water pollution. Franklin wanted the polluting industries moved outside the city. This had already taken place in Boston, New York and other cities at the time.

The brick bridge and a nearby placard remind us that conservation, public health, and concern about the environment are routine features of public life, not only in our own era, but also in history at nearly any time or place. And Franklin’s 1739 water pollution controversy is a classic example.

The brick bridge and a nearby placard remind us that conservation, public health, and concern about the environment are routine features of public life, not only in our own era, but also in history at nearly any time or place. And Franklin’s 1739 water pollution controversy is a classic example.

It is also an example of the way the media record can be a source of information today about little-known environmental and public health controversies in the past.

Franklin’s newspaper rival, Andrew Bradfordm, was the first printer in Pennsylvania and among the first in the US. His Philadelphia operation opened in 1713 and he published the first edition of the weekly Mercury on Dec. 22, 1719 (Willard, 1938). The newspaper, he said, “shall contain an Impartial account of Transactions, in the Several States of Europe, America, etc.”

Franklin had become editor of the Gazette when he purchased Bradford’s failing competitor called the Pennsylvania Gazette. He published his first edition on October 2, I729 (Clark, 1989). “The Author of a Gazette,” he wrote, ought to have “a Great Easiness and Command of Writing and Relating Things cleanly and intelligibly, and in few Words; he should be able to speak of War both by Land and Sea; be well acquainted with Geography, with the History of the Time, with the several Interests of Princes and States, the Secrets of Courts, and the Manners and Customs of all Nations.”

A great publishing rivalry

The two publishers were a generation apart – Bradford was born in 1686 in York, England, and Franklin in 1706 in Boston. Bradford was originally a reformer and was often critical of government, but became aligned with the old establishment of the Pennsylvania proprieters.

Bradford also published the “Busy-Body” essays, written by Franklin and Joseph Breintnall, before Franklin purchased the Gazette in 1729.

Franklin did not think much of Bradford. He was “poorly qualified for their business… and was very illiterate,” Franklin said in his 1771 autobiography. The Mercury was “a paltry thing, wretchedly manag’d, (and in) no way entertaining.” The feeling was mutual, and over time, the two became great rivals.

Franklin was a shrewd and competitive businessman. Around 1731, he got Bradford fired for doing a poor job printing an important government document. As Franklin said, it was printed in “a coarse, blundering manner.” Franklin took it on himself to reprint it “elegantly and correctly,” and then sent a copy to every member of the Pennsylvania House. “They were sensible of the difference: it strengthened the hands of our friends … and they voted us their printers for the year ensuing.”

Bradford also lost his job as postmaster to Franklin. While serving in the position from 1728 to 1737, Bradford apparently served some of his own interests, and meanwhile was unkind enough to forbid his riders from carrying Franklin’s Gazette, although the riders would often carry Franklin’s mail privately. In 1737, Bradford was removed from the office and Franklin was appointed as his replacement.

And so the 1739 controversy over Dock Creek took place against a backdrop of rivalry, and at a time when Bradford’s fortunes were declining and Franklin’s were on the rise. Although his experiments with electricity and his involvement in revolutionary diplomacy were still ahead of him, his civic leadership at the city and state levels had become widely admired in the 1730s. He created a civic group (the Junto) that established Philadelphia’s first lending library in 1730, the first volunteer firefighting company in 1736, and would go on to help found the first Pennsylvania university in 1743 and the first state hospital in 1751.

Franklin thought about Dock Creek pollution as one of the “small matters” that ought to concern civic leaders. Laws about dumping trash were on the books in Philadelphia and other cities in the American colonies. As early as 1657, for example, New Amsterdam (New York) had a law making each resident responsible for his own trash (Melosi, 1981). In Boston, between 1692 and 1708, trades that were considered a nuisance, like tanneries and slaughterhouses, were removed from the city limits. In 1711, the legislative body in colonial Boston placed fines on those who used “the old Dock” to dispose of dirt or trash. (Christopher, 2020)

At the time of the Dock Creek controversy, Philadelphia was the second largest British city in the North American colonies, with a population around 13,000. Boston was first, with 16,400 and New York was third, with 11,000 (Lydon, 1967). The city was dominated by Quakers, a Protestant denomination, and William Penn’s heirs, who controlled the colony and its politics as proprietors. As a result, reforms that should have taken place did not, and this may have been a particular problem with water pollution in Dock Creek.

Usually, household garbage, horse manure and sewage accumulated in the streets until it was swept away by the next rainstorm. In small communities this was not an enormous problem, but as towns became the focus of increasing commercial activity in the 18th and 19th centuries, the urban environment became a focus of greater concern. In a growing town like Philadelphia, pollution was an important issue; in a great city like London, it was a public health disaster.

The petition and the protest

The Philadelphia water pollution conflict of 1739 began on May 15 of that year when a group of Philadelphia citizens presented a petition to the Pennsylvania Assembly to stop water pollution in the city’s commercial district. Leather tanneries, slaughterhouses and breweries were dumping their wastes into a small tributary of the Delaware River called Dock Creek that ran through the city. Franklin probably signed it, but even if he did not, it is clear from his reporting in the Gazette that he was in favor of cleaning up Dock Creek. The petition asked the Assembly to declare the tanneries a nuisance and asked that they be “removed in such Time as might be tho’t reasonable.”

Describing the problem, Franklin noted that “many offensive and unwholesome smells do arise from the Tan-Yards, much to the great Annoyance of the Neighborhood.” In an article in his newspaper, the Pennsylvania Gazette, Franklin said the Tanners “…choaked the Dock — which was formerly navigable as high as Third Street — with the Tan, Horns, &c.:” (Franklin, 1739).

Franklin was no disinterested protester, said historian A. Michael McMahon. “His residences and business properties in the area involved him personally, and as an affluent citizen desiring to protect his investments… Perhaps more than his fellow citizens, [he] saw the problems as inherent in unchecked growth…” (McMahon, 1992; Double, 2013).

Franklin and the petitioners noted that the smells affected property values and that the waste choking the creek limited its use in fighting fires. They also said if the creek were not polluted it would be “of great use” for delivering supplies to the city. The Dock had been created “for publick Service.” Franklin’s argument was for “public rights,” and the restraints on the liberty of the tanners would be “but a trifle” compared to the “damage done to others, and the city, by remaining where they are.” Franklin also noted a compromise position: “If the tanners could be so regulated to become inoffensive, the Petitioners declar’d that they should be therewith satisfied.”

The tanners responded with their own petition, proposing to wash the pavement once a day, build a fence around the tan yards, and release the waste into Dock Creek only at high tide. They also found a champion in Franklin’s rival, Andrew Bradford, whose American Mercury defended the liberty and property rights of the tanners.

On August 27, 1739, a committee of the Assembly heard the petition. Sometime before the hearing, perhaps that day, the tanners staged a parade through town, carrying their grievances to the people and insisting on their rights. The Assembly heard both sides, but what happened next is unclear. Apparently, Bradford’s Mercury carried an article falsely stating that the environmentalists’ petition had been rejected. Its headline was: “A Daring Attempt on the Liberties of the Tradesmen of Philadelphia.”

Franklin’s temper boiled at this apparent misinformation, and he printed the full text of the Assembly resolution, which supported the environmentalists. The resolution declared that the water pollution was indeed a nuisance and that regulations should be drawn up. “It is hard to imagine what could induce the tanners to publish a relation [account] so partial and so false,” Franklin wrote. “In Prudence they ought not to have triumphed before the victory.” It wasn’t a question of the liberties of the tradesmen but rather “only a modest Attempt to deliver a great Number of Tradesmen from being poisoned by a few, and restore to them the Liberty of Breathing freely in their own Houses.”

One reason why reform proposals ran into so much opposition was that the slaughterhouses, tanneries, and breweries were owned by leading Quaker citizens of Philadelphia. Six of the ten tanneries were the property of William Hudson, a Philadelphia resident from a family of tanners in York, England. Hudson was a mayor, alderman and judge – as well as a businessman – and was also the owner of Hudson’s Square, a city park that is now the site of the Liberty Bell exhibit. The list of prominent polluters would be incomplete without the most important brewers in Philadelphia — Anthony Morris and his son, Quaker leaders from a family of brewers in Stepney, England. They also served as mayors in 1704 and 1738.

These business leaders would have worked together, since the supply chains for beer, meat and leather are interconnected. Brewers sell leftover grain “slops” to feed cattle, which are kept until slaughtered for meat. Afterward, the cattle hides are used to make leather. All of these activities create a tremendous amount of waste water.

It’s well known that Franklin used his newspaper to criticize the “proprietors” and the Penn family establishment of Philadelphia, and the slaughterhouse and tannery owners were leaders of that faction. As biographers have noted, Franklin stood up for tradesman and the “leather aproned” working classes of Philadelphia.

It’s not clear just when the tanneries were subsequently cleaned up, but they were not moved, to Franklin’s chagrin. The 1739 environmental victory, in the end, was merely symbolic, although it had many of the elements that would emerge in later environmental controversies: battling editors, inaccurate articles, petitions, demonstrations, legislative hearings and ambiguous victories.

Dock Creek and yellow fever, 1740s

Two years later, an epidemic of yellow fever that killed 500 Philadelphia residents was blamed on the pollution from Dock Creek. Philadelphia’s leading physician, Franklin’s friend Thomas Bond, said in a 1741 article that the creek was linked to malaria and other diseases and that not so much “bark” (quinine) would be needed if the waterway would be filled in (McMahon, 1992).

The epidemic led to a new round of concern about Dock Creek, and by 1747, Franklin was appointed to a committee to consider what to do about restoring it. The committee recommended an extensive sewer system, and a rebuilt dock that could accommodate various sizes of boats. However, the proposal was defeated due to its high costs. Over the years, a few private attempts to deal with garbage removal and build sewers could not keep pace with the expanding tanneries and distilleries along the creek and nearby river. Philadelphia’s environment deteriorated, and more pressing political priorities in London took Franklin’s attention.

In 1763, however, Franklin returned briefly to Philadelphia and was involved in a new effort to finance and organize street cleaning and storm water drainage. Twenty five years after the original Dock Creek petition, a new proposal to clean and maintain the creek was considered, but a committee found the area totally polluted and “in great measure useless.” Soon, workers began to cover Dock Creek.

Around the same time, Franklin served on other committees that took a comprehensive approach to municipal planning, street lighting, waste disposal, police work and firefighting. He could not have been fully satisfied with the outcome of his work, according to McMahon. Although the 1760s ordinances looked like progress, “for those who fought to save the Dock and to reclaim the center of the city for residences and small-scale crafts and retail shops, those acts capitulated to manufacturing interests and uncontrolled growth.” (McMahon, 1992).

Franklin saw Dock Creek as a valuable part of the city because it allowed small boats hauling fuel and building materials from nearby farms to reach the commercial district. “Franklin envisioned a benign balance between city and country, with each supplying the economic and social needs of the other,” said McMahon. He disliked the domination of manufacturing interests in the city. Like Thomas Jefferson and other agrarians of the era, he strongly believed that the country instilled moral virtues and that the city tended to drain them. At one point Franklin wrote that he was glad that many ages would pass before Americans would be forced into the cities as they had been in England. (Franklin, 1751).

Franklin’s will included funds for clean water projects

In the political turmoil of the next three decades, the 1760s ordinances were ignored. When Franklin arrived in Paris in 1767, beginning an ambassadorship that would culminate in French support for the American revolution, one of the first things he noticed was that Paris had a system of sewers that was “much more modern” than that of London, as well as a filtration system for drinking water (Fay, 1939).

After the revolution, when he returned to Philadelphia, he worried about the continued epidemics of yellow fever in his home city, which he attributed to the poor quality of water from old wells and contaminated springs. The water, Franklin wrote, would “gradually grow worse” and “in time be unfit for use, as I find has happened in all old cities.”

In his final year, 1789, Franklin wrote a codicil to his will leaving money for Philadelphia to build a conduit to bring clean water from Wissahickon Creek into the town. The project was not carried out as he intended, but a devastating yellow fever epidemic, which killed a quarter of Philadelphia’s population in the mid-1790s, led to the formation of the Watering Committee of Philadelphia to build the water line. However, to save money, a shorter fresh water line to the Schuylkill River was built in 1801.

Building the shorter water line was short sighted. Hundreds of industries crowded the Schuylkill River and polluted the water intakes by the mid- to late-19th century. Repeated complaints about the factories and their impact on drinking water were made, but to no avail. The dye works, the oil refineries, the mills and the breweries continued to pollute the river, and their destruction of it amounted to a “wanton outrage on common decency,” in the view of one engineer.

But the public outrage was insufficient to overcome the resistance of manufacturers to paying for a sewer line, and in 1867, the Pennsylvania legislature rejected a proposal to regulate water pollution. “Makeshift engineering” and corruption dominated the city’s water and sewer development later in the 19th century, and prominent engineers bitterly complained that the “vile waters” of the Schuylkill flowed directly into Philadelphia’s homes (McMahon, 1988).

Franklin as an environmental journalist and scientist

Franklin’s concern about water pollution is consistent with both his civic organizing and his well-known scientific work studying electricity.

Franklin was considered America’s first scientist, but he was also the first environmental scientist, or, as Michael Mann has argued, the first climate scientist. “Among other subjects, he engaged in the study of weather patterns and researched the behavior of the Gulf Stream, centuries before it became fashionable,” Mann said. “He also promoted improved chimneys to reduce the accumulation of smoke in houses, and devices like his streetlamp reduced the emission of smoke into the air.”

History provides important context for assessing the environmental threats we face today, Mann said.

Dock Creek Timeline

—– May 15, 1739 — Merchants of Philadelphia present petition about moving tanneries

—– August 16, 1739 — Andrew Bradford’s American Weekly Mercury objects to the petition on behalf of the tanners.

— August 30, 1739 — Benjamin Franklin’s Pennsylvania Gazette defends “public rights” agains water pollution

— September 6, 1739 — Bradford responds (Courtesy of the Pennsylvania Historical Society)

|

— Sept 13, 1739 — Bradford’s Postscript (Courtesy of the Pennsylvania Historical Society)

|

References

Bill Double, “Scenic Stream to City Sewer,” National Park Service, 2013, Online http://npshistory.com/publications/inde/dock-creek.pdf

Bernard Fay, Franklin: The Apostle of Modern Times (New York, Little, Brown & Co., 1929): 341.

Walter Isaacson, Benjamin Franklin, An American Life, (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2004).

Bill Kovarik, The Ethyl Controversy, Dissertation, University of Maryland, 1993. DAI 1994 55(4): 781-782-A. DA9425070

Michael McMahon, “‘Small Matters’: Benjamin Franklin, Philadelphia and the ‘Progress of Cities,'” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, 66:2, April, 1992: 157.

Mark Neuzil and Bill Kovarik, Mass Media and Environmental Conflict, Sage, 1996.

Pennsylvania Gazette, Aug. 23 – Aug. 30, 1739: 1. Online: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.31970021322984&seq=409

J. Willard, William Tailer, John Clark and Anna Janney de Armond, “Andrew Bradford,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography , Oct., 1938, Vol. 62, No. 4 (Oct., 1938), pp. 463-487.

Text of Franklin’s Dock Creek article

Aug. 30, 1739 (spelling edited for clarity)

The Tanners of Philadelphia, having in the Mercury of August 16. published a partial Account of the Hearing before the Assembly, on the Petition relating to Tan-Yards, &c. magnifying what was said on their own fide, and stifling everything that was argued by the Petitioners in support of their Petition, you are de-is fired to give the Publick the substance of what they have suppressed, which is as follows.

The Prayer of the Petition was, that the erecting new Tan-Yard, &c. within the Bounds of the City, should be forbidden, and that those already created should be removed in such Time as might be tho’t reasonable: And the Reasons given by the Petitioners were, in short, that many offensive and unwholesome Smells do arise from Tan-Yards, to the great Annoyance of the Neighborhood, and therefore to the great Injury of all those who have Lots or Tenements near them, as it considerably lessens the Value of such Lots and Tenements. That the Dock-Street, upon which the Tanners are seated, was given with the Dock for publick Service, but that the Tanners had taken up and encumber’d the Street with their Pits, &c. and had choaked the Deck (which was formerly navigable as high as Third Street) with their Tan, Horns, &c. That the said Dock if open might be of great Use in several respects, and particularly in the case of fires in that part of the Town; but as it now lies, is a grievous Nuisance. That the Smoke arising from the burning Tan [bark] fills all the neighboring houses, and is exceedingly offensive. That there are, not very far from the Town, Places which might be as convenient to the Tanners, and not so injurious to the City. That if they were in some reasonable time to remove, their Grounds by the great Improvements that would be made near the Dock, would become more valuable to build on, than to be us’d as Tan-Yards; But however, as the Tanners who own Land on the Deck are very few, and the People whose Interest is affected by their Remaining there, are a very great Number, the Damage they would suffer in removing, would be but a Trifle, in Comparison to the Damage done to others, and to the City, by continuing where they are. Notwithstanding which, if the Tanners could be so regulated as to become inoffensive, the Petitioners declar’d that they should be therewith satisfied.

Upon which, the Tanners themselves proposed the following Regulations, viz:

A convenient Method for the better regulating of Tan-Yards, submitted by the Tanners to the Honorable House of Representatives of the Freemen of the Province of Pennsylvania.

Let the Tanyards be well paved between all the Pitts, and wash’d once every Day: Let the Watering-Pools and Masterings (which are the only Parts that afford offensive Smells) be enclosed on every Side and roofed over, within which Enclosure may be subterranean Passage to receive the Washings and Filth of the Yard into the Dock or River at High Water: Let the whole Yard is likewise enclosed on all Sides with some standing chase-Fence, and kept seven or eight Feet high, and every Tanner be obliged every week to cart off his Tan, Horns and such offensive Offals.

William Hudson, Jr. John Ogden

Samuel Morris John Howell

William Smith

John Snowdon being out of Town, we the Subscribers declare his Assent to the above Proposal.

Samuel Morris John Howell.

These are the Proposals of the Tanners themselves to prevent or remove the Nuisance arising from their Tan-Yards, by which tis confess’d that they now are, and ‘tis certain they have long been, a Nuisance.

What Regard these Gentlemen in the Mercury have shown to Truth may be observ’d from the Account they give of the Assembly’s determination, on the Affair viz. “Upon the whole the Petition was REJECTED, the Tanners Right to follow their Trades within the City, ACCORDING TO THEIR OWN PROPOSALS, asserted, and the Corporat6ion to see that they comply’d with SUCH a Regulation.”

If this be compar’d with the following Extract from the Minutes of the House, viz.

“After a full Hearing of both Parties, Resolved:

That the City of Philadelphia being the Place where the Tan- Skinners, &c. have planted their Vats, Lime-pits, &c. The Inconveniencies arising from those Yards and Pitts must be best known there; It is therefore referred to the Mayer and Commonality of Philadelphia, by an Ordinance for that Purpose, to make such Provision for the Relief of the Petitioners, against the Tanners, Skinners, Butchers, &c. as they shall find to be necessary and consistent with the Powers of their Corporation: And that if it shall appear to them, that the Aid of the Legislature is wanting to compel Obedience to such necessary Orders or Regulations as they shall make in that Behalf, that they apply to the General Assembly of this Province for the Time being for that Purpose. And the Tanners having proposed to this House certain Regulations for preventing the Inconveniences complained of, arising from the Tann yards, it is further ordered, That a true Copy of the said Proposals be delivered, with a Copy of this Resolve, to the Mayor of Philadelphia for the Time Being.”

It is hard to imagine what could induce the Tanners to publish a Relation, so partial and so false; Did they imagine the Mayor and Commonalty would never hear of the Resolve of the House or Regulations, viz. that the long-injured Petitioners would forget to prosecute their Petition, according to the Direction of that Resolve?

In Prudence they ought not to have triumph’d before the Vic- tory; and in Justice they should not have call’d that a Daring Attempt on the Liberties of the Tradesmen of Philadelphia, which was only a modest Attempt to deliver a great Number of Tradesmen from being poisoned by a few, and restore to them the Liberty of Breathing freely in their own Houses. But an Inclination to stir up Faction, Heats and Animosities a- among Fellow-Citizens, who should live in Love and Peace, will carry some Men thro’ thick and thin. I cannot think, however, that all the Tanners are of that Disposition; and I doubt the Hot- Heads which produc’d that Paper, and call’d it The Account of the Tanners, will not be thank’d for it by some of their own Brethren.