By Bill Kovarik

By Bill Kovarik

(Reflections on the NY Times Innovation report, an internal investigation that should have begun more than a decade ago, and that, even today, barely scratches the surface).

In 1911, a young muckraking journalist named Will Irwin began a 14-part series in Colliers magazine called The American Newspaper. He profiled great editors, considered media ethics and described sensationalism and advertiser influence.

The American newspaper, he said, was “wonderfully able, wonderfully efficient, and wonderfully powerful (but) with real faults.”

The main fault was this:

It is the mouthpiece of an older stock. It lags behind the thought of its times. . . .To us of this younger generation, our daily press is speaking, for the most part, with a dead voice, because the supreme power resides in men of that older generation.

Of course, Irwin was writing for a magazine, which, during the muckraking era, was the medium that was actively circumventing newspapers and the AP-Western Union monopoly.

In the spirit of Will Irwin, I started visiting newsrooms to ask how they were coping with the new media about 15 years ago. I was working on textbook called “Web Design for Mass Media” published in 2001. Would the Web help the news business? Would it hurt? Most of all, was it (in the words of Henry David Thoreau) just an improved mean to an unimproved end?

What I found was intriguing, alarming and appalling.

In the late 1990s, at a key moment when the innovative cycle was still wide open, few of the newspaper Web operations were even communicating with the newsroom. At the Baltimore Sun, for example, Web operations were on the first floor (not the third-floor newsroom), in a tight space carved out from classified advertising. (This is ironic, I suppose, since classifieds were the first to fall to the digital onslaught. Soon there would be plenty of room on the first floor). The web people were recent journalism and computer science graduates. They were not allowed to join the union, or participate in big decisions. They hoped some day to move “up” to the third floor.

Web operations for the Washington Post were located all the way across the Potomac River in Roslyn. They, too, were similarly divorced from the “real” newsroom.

Few of the operations were anything more than a way to publish teasers for the newspaper. Many organizations preferred to publish with front pages “frozen” into clickable zones, in the hope that the nerds shoveling content onto the web would not inadvertently publish lawsuit-generating mistakes.

Meanwhile, small experiments in community involvement had generated such venomous commentary that they were abruptly terminated. Automatic filtering and the establishment of some rules helped open comment areas, but they soon filled with trolls and became largely irrelevant. The cloistered world of journalism would remain closed, it seemed.

Like most of these newsroom disasters, web operations for the New York Times were located in a separate building. Unlike most, they were being run by veteran reporters and editors. One of these editors, Rich Meislin, told me that they were not simply shoveling the old content into a new envelope, but rather, finding new ways to use this exciting new medium. One of their favorite projects at the time was digitizing the 92nd Street YMCM talks, with speakers ranging from Allen Ginsberg to Vladimir Nabokov. It was the kind of thing that could never be done in print. So yes, at least at the Times, and at least in terms of some content, the new media could be more than a new means to an unimproved end.

The separate web operation by 2005 migrated back into the main Times newsroom, which was both a blessing and a curse, since it meant fewer possibilities for experimental work but better integration into the news operation.

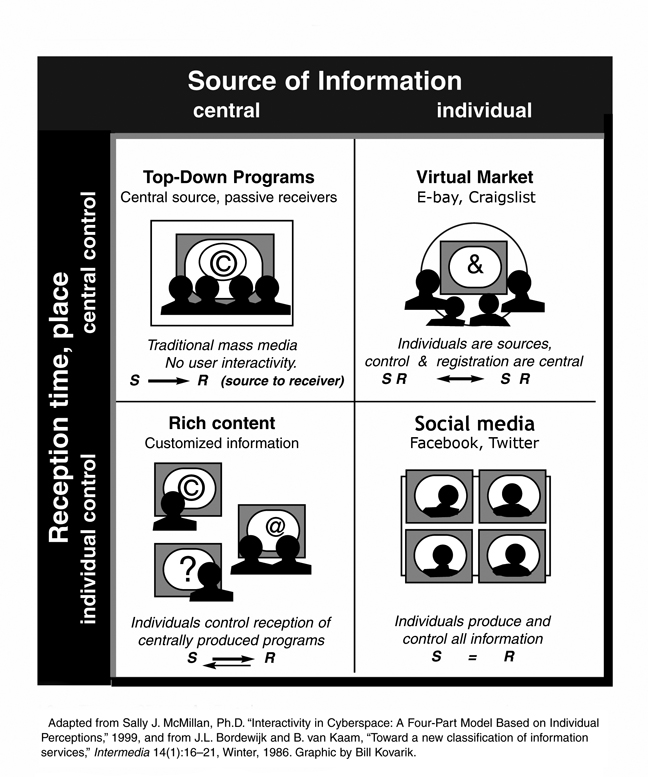

The Times, the Post and others began to create notable online projects that took advantage of the medium’s interactive graphic possibilities in projects like the 2012 Times’ “Snow Fall” and the Post’s 2010 “Top Secret America.” Both are stunning, deep uses of new technology. But they are, after all, top-down products that are not deeply linked to the communities they report on. What if the source of the information had not been “Central” (as seen in this chart) but rather Individuals? What if the “Information Traffic” patterns of the news business had followed or even led the public stampede towards social / virtual community media?

This is just the beginning of the problem, a starting point which I tried to describe in 2011 for Revolutions in Communication, and also in a separate essay about Who (or what) killed the American newspaper?

The problem is that little to nothing was spent on research and new product development in the crucial decades starting in 1990. Although there were minor flops at Viewtron and Prodigy in the 1980s, the startling success of Minitel in France never seemed to illuminate the corporate minds. So by the late 1990s, the list of other projects that folded up included the Information Design Laboratory, New Century, Digital Cities, and Classified Ventures.

These efforts were quite anemic, by the way; pale tea as Southern journalists used to say. While most industries spend at least five to 10 percent of their profits on research and development, the publishing business never even came close. They didn’t have the motivation.

What did motivate the management a merciless squeezing of all these institutions for everything they were worth. Old timers have incredible stories about people sleeping in their cars while the owners cruised the skies in lear jets. Old timers will remember how, in the early 1990s, editors and publishers were resigning in disgust because they were being asked for 25 percent or 30 percent ROI numbers, and the only way to achieve that was to lay off newsroom staff. It wasn’t that the newspapers weren’t profitable, merely that they could never satisfy the gaping maw of Wall Street.

So, yes, blind greed and a lack of research were major elements. But another big one was the inability of publishers to see themselves as public service enterprises in a general sort of way. News, of course, is one variety of public service enterprise. But did editors and publishers attempt to serve and empower the varieties of communities within their pale? No. They stood by while others with serious information needs thrashed around, looking for circumventing media. Every time some new enterprise proved successful, such as Landmark’s experiment with the Weather Channel, they spun it off on its own.

Journalists didn’t lead the charge for change in part because, by the mid-20th century, the mythology of journalism demanded that it be a “cloistered profession” with its own codes, trade secrets, and internal loyalties.

Look at page 25 of the Times Innovation report. There’s a graphic entitled “What are we trying to do?” The ideal, it seems, is to move in this sequence: “non-readers –> drive by–> repeat readers –> registered reader –> subscriber –> loyalist.”

Loyalist? Say what? Like a news Tory, as opposed to a news Whig? Despite its many accomplishments, and the relative good will built up over many decades of journalistic service, few people will want to be considered Times Loyalists. It’s crassly self-promoting and historically regressive.

There are a few redeeming sections of the report. For instance, on p. 31 there is a “best practices” section for keeping track of experiments — an idea that is hardly novel outside the news industry, but one that ought to be shouted from the rooftops to the news Tories.

But for the most part, the focus is on promotion, packaging and using the existing resources to maximum commercial effect.

So in that sense, the Innovation report is misnamed. It’s really a Tory call to news loyalists in the hope they will rally around the standard and defend the last bastions.

Sadly, it’s too small for a once-great institution and too late for the digital revolution. It’s spoken in the dead voice of an older generation.

It doesn’t have to be a eulogy, though. There are plenty of new ideas out there , about how to build community, about how to achieve what Walter Lippmann predicted would be the fourth stage of the media: Organized intelligence.*

Here’s one thought: It doesn’t revolve around loyalty or packaging. If anything, it revolves around community building. It revolves around the press sharing its own power to empower others, as it should have done all along. It involves the Times role as the one of the last leaders still standing and the ethical responsibility to forge a new way forward.

————————————————————————–

* Lippmann’s four stages: 1) Totalitarian; 2) Partisan (Tory/Whig, Republican/Democrat); 3) Commercial / Penny Press; 4) Organized Intelligence.

*

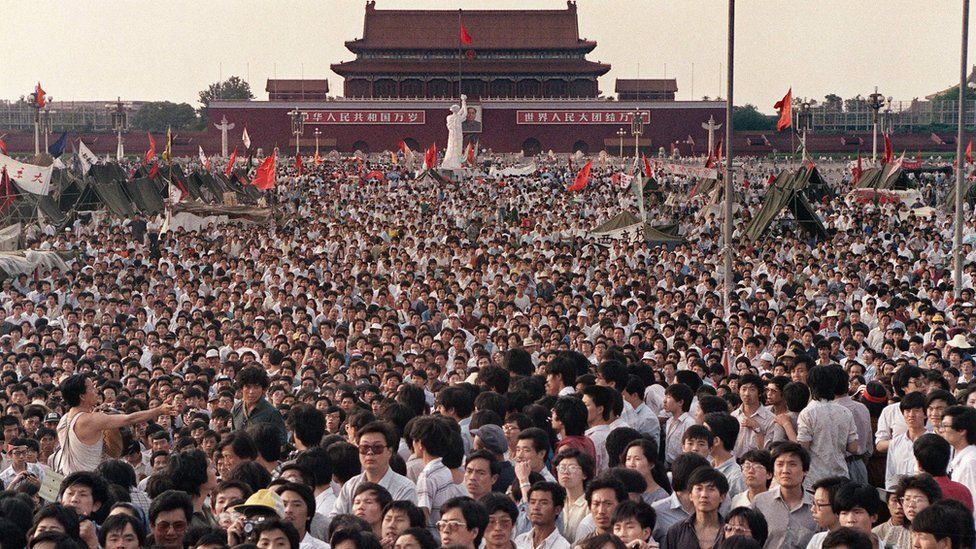

Tienanmen Square protests

Tienanmen Square protests Media law and ethics

Media law and ethics

Early Dageurotypes

Early Dageurotypes

Ida B Wells

Ida B Wells Dorothea Lange

Dorothea Lange

William Yukon Chang’s

William Yukon Chang’s Margaret Bourke-White

Margaret Bourke-White  Tank Man

Tank Man  Harold Edgerton

Harold Edgerton Evelyn Berezin,

Evelyn Berezin, PBS archives

PBS archives Virtual Reality

Virtual Reality /https://public-media.smithsonianmag.com/filer/b4/ec/b4ec2608-cfe6-4187-a1de-7dbe856c1e11/lowell_thomas_magic_dials_1.jpg) Lowell Thomas

Lowell Thomas

Clare Hollingworth

Clare Hollingworth Ring Lardner

Ring Lardner  TV and US Civil Rights

TV and US Civil Rights  Unrecognized women of ENIAC

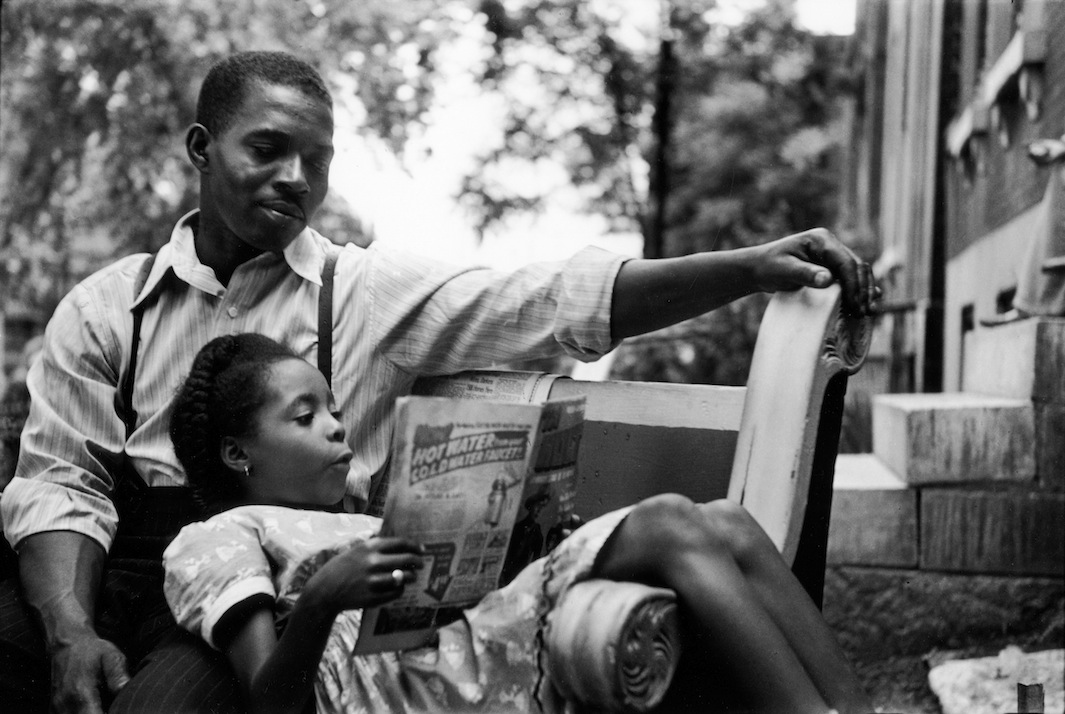

Unrecognized women of ENIAC Lost Gordon Parks photos

Lost Gordon Parks photos Birth of a Nation turns 100

Birth of a Nation turns 100 The Wipers Times,

The Wipers Times,  Ixnay on the Otography-fay

Ixnay on the Otography-fay Nixon-Kennedy debates

Nixon-Kennedy debates  Dorothea Lange

Dorothea Lange  Too Fast for the Truth?

Too Fast for the Truth?

Dr. Zhivago

Dr. Zhivago Margaret Fuller

Margaret Fuller

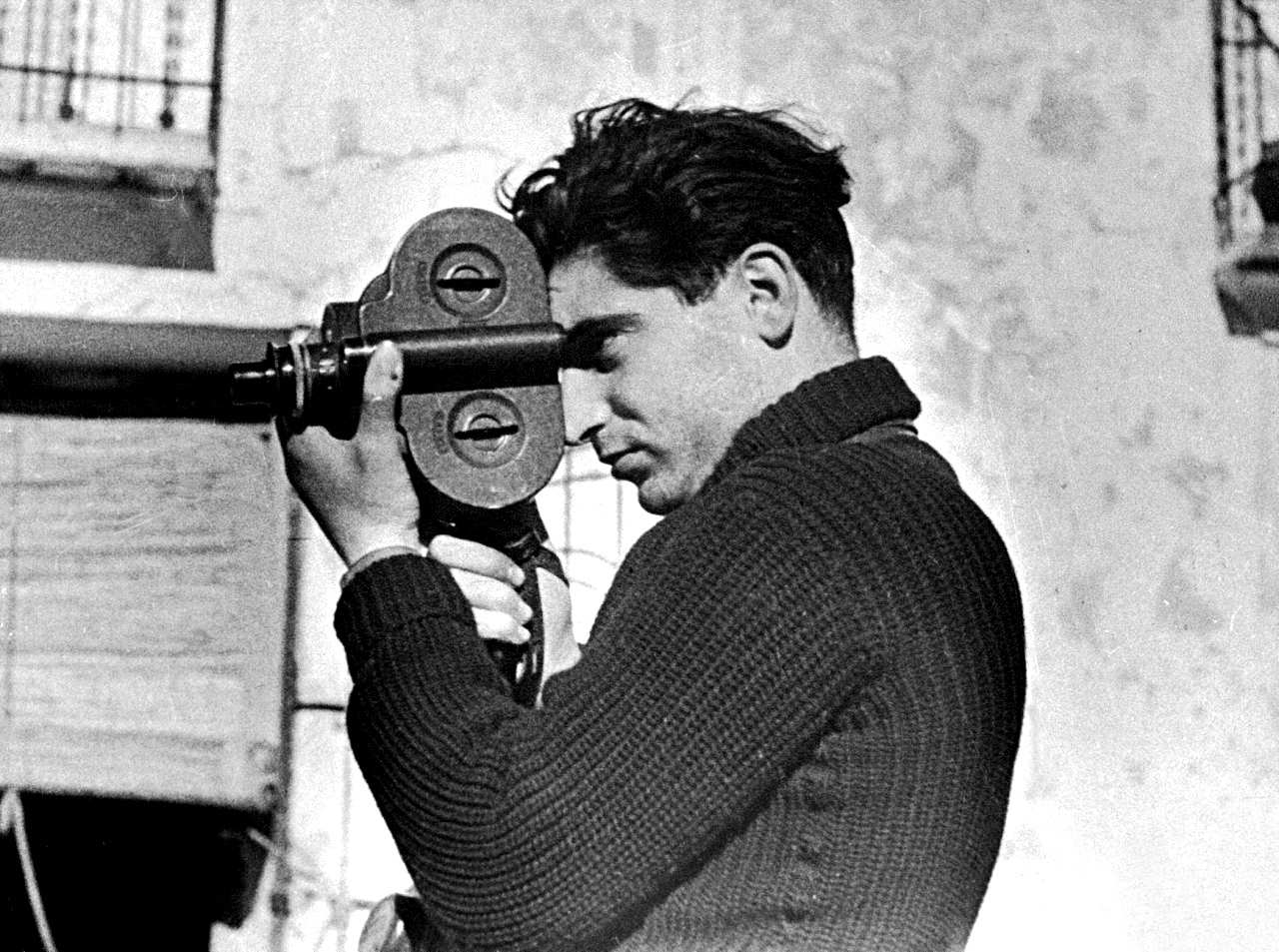

Early Orson Wells film

Early Orson Wells film

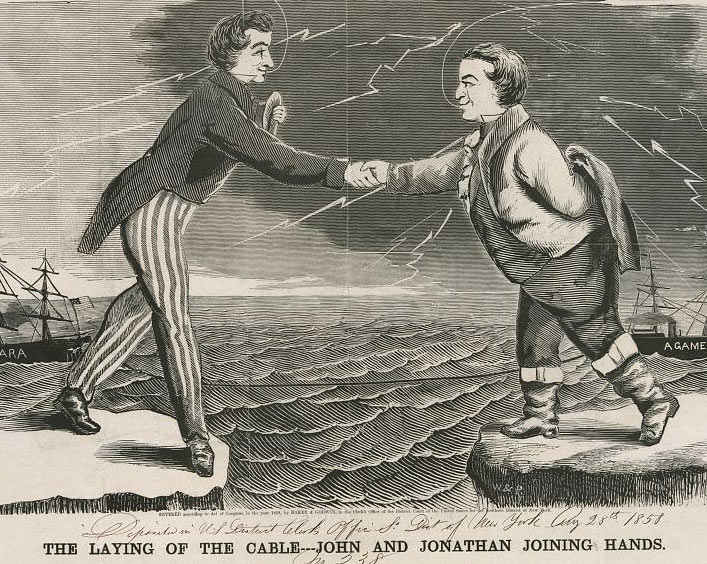

Cartoons that changed the world

Cartoons that changed the world

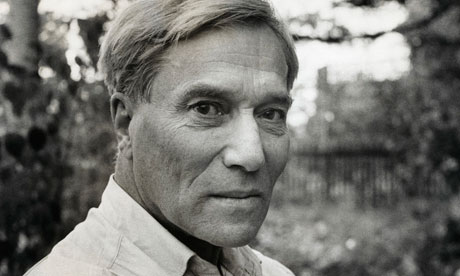

James Gordon Bennett Jr.

James Gordon Bennett Jr.