Revolutions in Communication is about the printers, reporters, photographers, filmmakers, advertisers, PR practitioners, broadcasters, computer geeks, and all the rebels and visionaries who were ahead of their times, who led the times, and who created The Times. This critically acclaimed survey of media history is now in a third edition, available from Bloomsbury, Amazon and other booksellers.

Revolutions in Communication is about the printers, reporters, photographers, filmmakers, advertisers, PR practitioners, broadcasters, computer geeks, and all the rebels and visionaries who were ahead of their times, who led the times, and who created The Times. This critically acclaimed survey of media history is now in a third edition, available from Bloomsbury, Amazon and other booksellers.

Revolutions in Communication surveys the history of all major communications disciplines, including journalism, photography, cinema, advertising & public relations, radio, television, computing and networked social media.

Revolutions in Communication is the leading global media history textbook, consistently rated in the top 50 Media Studies books at Amazon.* The book has been widely adopted in college classrooms from NYU to USC, from Western Ontario to Florida International, and from Britain t0 China, Italy, India, and many others. (A list of confirmed adoptions is below).

Media technology in history

The narrative in Revolutions in Communication centers around technological change — a common thread that unites global media history. This approach also provides a much-needed alternative to the heroic, nationalistic and professionally oriented narratives that have guided media history in the past.

Technological change has been a major point in communications history for decades. As Marshall McLuhan famously said: “The medium is the message,” meaning that the technology has an important or possibly dominant influence on the content. That view is called technological determinism.

McLuhan notwithstanding, human needs also shape technology, that is to say: The need for the message helps create the medium. Or as famed musician David Bowie once said, it was the end of “singularity” in world culture that produced the internet. So instead of the usual narrative about how the media affect society, Bowie and others think that a positive turn in global culture helped create new digital media.

This shouldn’t be a surprise. Historical study shows that most innovations in communications technology stem in part from the social needs that drive inventors. These needs might include a vision of a more flexible new technology or a desire to circumvent older media that don’t speak in the voice of a new generation. That view is called social construction of technology.

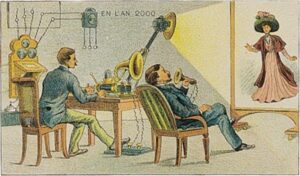

One example would be Albert Robida’s 1890 cartoon of a “telephonoscope,” published many decades before the introduction of TV. Here a perceived social need to better communicate over distance is being projected, perhaps in the hope that such a technology might be developed. Another example might be the use of magazines for muckraking when (according to Will Irwin’s 1911 survey of the news business) newspapers did not speak in the voice of Irwin’s own generation.

One example would be Albert Robida’s 1890 cartoon of a “telephonoscope,” published many decades before the introduction of TV. Here a perceived social need to better communicate over distance is being projected, perhaps in the hope that such a technology might be developed. Another example might be the use of magazines for muckraking when (according to Will Irwin’s 1911 survey of the news business) newspapers did not speak in the voice of Irwin’s own generation.

Similarly, Vannevar Bush and H.G. Wells envisioned an interconnected global library fifty years before Tim Berners-Lee invented the World Wide Web. Others in the free software movement invented technologies that helped the web remain an open rather than closed system.

The same theme of socially constructed circumventing technologies can also be found in the histories of printing, imaging and broadcasting.

Revolutions in Communication takes the view that social vision and community awareness have at least as much to do with the development of technology as the deterministic internal logic of a technology’s technical path. It’s the reason why the early 20th century muckrakers published in magazines, and not newspapers. It’s the reason why the penny press was so successful in the 1830s and the press barons of the late 19th century were able to create newspaper empires.

Conversely, the lack of vision and failure to serve their communities are also among the reasons why newspapers collapsed so spectacularly in the first decades of the 21st century; why Kodak not only invented digital imaging but was bankrupted by it; why digital streaming kicked the stuffing out of the Hollywood machine and why cable TV monopolies lost their markets.

The important issue now is the role of all four media revolutions in the emerging global culture. Will we finally understand and address the needs of the global population, relegating hunger and curable disease to distant memory? Can we overcome the tendency to destroy the environment, and each other, in the name of ideologies?

The great hopes that were once held for these new communications technologies have dwindled as we realize that they are also capable of creating a “surveillance state” that might make George Orwell’s “1984” seem tame by comparison. But lost hopes may be part of the price of maturity.

In any event, communication will play a central role in future years, and we need to understand how we arrived at this moment in history.

About the history of mass media:

It’s no longer sufficient (if it actually ever was) to continue presenting an isolated, progressive, narrative history of American journalism. This is not to be overly critical of previous textbooks but rather to say that times are changing and, as usual, media historians are struggling to catch up.

Surely the fact that electronic and digital media have broken down international barriers must be part of any serious treatment of media history today. Surely, also, the interdependent nation-state / print media institution, with a relationship now over five centuries old, is only one thread of an emerging global media history that should also include the digital communications revolution.

As Mitchell Stevens said in his Call for an International History of Journalism:

To attempt to separate the history of American journalism from developments overseas seems … as foolish as attempting to separate the history of journalism in Ohio or Kansas from what was happening in Boston, Philadelphia and New York… A kind of ignorance – which would not be tolerated in literature departments, in theater departments, in art departments, in science departments – is routinely accepted in journalism departments. American journalism history is dangerously and unflaggingly parochial.

The same parochial nationalism is even more evident in public relations, advertising, broadcasting, and other communications fields, partly because in the past, communications history was usually valued only as career preparation. But historians who hope to inspire future generations by honoring the heroes of the past often oversimplify and omit the mistakes and connections that provide historical lessons and paths for ongoing inquiry.

Admittedly, an agenda that approaches both international breadth and historical depth confronts a serious problem from the outset: In a field that is already struggling to contain the size of textbooks (and student workloads), how could that be accomplished?

One solution is to take advantage of the new media that this book is designed to describe. So this book’s web site in intended to be one focal point for an international history of the media that is already begun on a variety of collaborative web sites such as Wikipedia. Since we live in revolutionary times, we ought to reflect and model those revolutionary new modes of communication in the collaborative and transparent way that communication history is written and appreciated.

With that in mind, students and scholars may find this book’s web site of some value for its links to wikis, timelines and other resources that can enhance international and interdisciplinary understanding of the history of mass media.

We are also particularly interested in research suggestions for students and in links to essays that describe the lives of media professionals in a cultural context or as part of a professional biography.

Getting started

Revolutions in Communication begins with the idea that the best way to read history is with a conceptual toolkit. Students should have some idea of what history is all about and why we study it.

So we begin with the Introductory Chapter that includes an overview of historians who exemplify different approaches to historical research and writing, and also a section on how historians have seen technology in general and media history in particular. Both are available at no charge through this web site.

This book then proceeds on a mostly chronological basis through the four mass media revolutions: print, visual, electronic and digital.

Revolutions in Communication concludes in Ch. 12 with the question of how we might use the awesome power of media to help transition from McLuhan’s “global village” to a mature, sustainable global culture.

Adopted in classrooms worldwide

Revolutions in Communication has been adopted as a textbook in history, computer science and communications department at dozens of leading universities, including:

- American University of Rome

- American University of Paris

- Bilkent University, Turkey (Syllabus)

- Binghamton University, New York (Syllabus)

- Brock University, St. Catharines, Ontario, Canada (

- Chinese University of Hong Kong

- City University of New York, Queen’s College (Syllabus)

- Colorado Women’s College (Syllabus)

- Dartmouth, New Hampshire

- Dibrugarh University, Assam, India (Syllabus)

- Florida Atlantic University

- Hebei University of Technology, China

- Humboldt State University, California

- Illinois State University

- Idaho, College of

- John Cabot University, Rome (Syllabus)

- Kabianga University, Kericho, Kenya

- Kadir Has University, Turkey (Syllabus)

- Karlova University, Czech Republic (info)

- Kolegji Universitar Beder, Albania

- London Metropolitan University, UK (Syllabus)

- Langston University, Oklahoma

- Marymount University, California (Syllabus)

- Mahatma Gandhi University, Kerala, India (Information)

- Makhanlal Chaturvedi National University of Journalism & Communication, Bhopal, India. (Syllabus)

- Masaryk University, Czech Republic (Syllabus)

- Masarykovi University, Czech Republic (Syllabus)

- Nitte, Mangalore, India

- New England School of Communication, Bangor, Maine

- New Jersey Institute of Technology (Syllabus)

- New York University (Syllabus) and (Syllabus)

- Ohio State University (Syllabus)

- Oregon State University (Syllabus)

- Pennsylvania State University

- Panjab University, Chandigarh, India

- Polytechnika Warszawska, Poland

- Radford University, Virginia (Syllabus)

- Ryukus University, Okinawa, Japan

- San Francisco University (Syllabus)

- Simon Frasier University, Canada

- St. Joseph’s University

- State University New York, Binghamton (Syllabus)

- Tezpur University, Assam, India (Graduate school)

- Umeå University, Sweden (Syllabus)

- Universitat Abat Oliba CEU, Barcelona, Spain (UAO-CEU.10616)

- University of Antwerp, Netherlands

- University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada

- University of California, Merced

- University of California, Los Angeles, Annenberg School of Communication (Syllabus)

- University of Colorado, Boulder

- University of Florida (Syllabus)

- University of Iowa (Syllabus)

- University of Ljubljiana, Slovenia

- University of Nevada, Reno (Syllabus)

- University of New Brunswick, Canada

- University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill (Syllabus)

- University of Oregon

- University of Toronto, St. Michael’s College, SMC 219

- University of Virginia, MDST 3050

- University of Western Ontario, Canada

- University of Wisconsin, Madison, and Stevens Point (COMM 190)

- Virginia Tech (Syllabus)

- Washington State University (Syllabus)

- Yeditepe University, Istanbul

- Zayed University, Dubai, UAE

The author welcomes contacts from colleagues and students — bill.kovarik at gmail dot com.

** In Febrary of 2025, Revolutions in Communication was Amazon’s #1 book in History of Communication & Media Studies in Canada, #149 for Amazon’s communications reference in the US, and among top media history textbooks in Europe and worldwide.