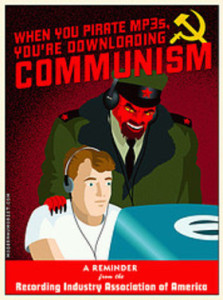

Parody poster, origin unknown, in protest of heavy-handed enforcement of music copyrights through the RIAA, for example, in the Tennenbaum and Thomas cases (below).

Controversy over music copyright used to involve disputes over relatively simple property issues. However, changes in music technology have complicated the issues since the 19th century.

In the 21st century, copyright issues have also taken on broad new cultural and even human rights dimensions.

For example, how should the law define fair use, or question the relentless pursuit of music pirates, or uphold moral rights for musicians, or keep copyright laws from stifling free culture in the name of free markets?

Many people outside the music industry have said that the laws are antiquated and should be adjusted to account for new technologies. The traditional institutions of the music industry are defensive, since new technologies have meant an enormous drop in revenues, (only some of which comes from music piracy). Musicians have been torn between various factions; older and better established musicians tend to side with the industry, while younger and less established musicians see opportunity in the new technologies.

History of music copyright controversy

Music copyrights go back to 1575 in Britain, and performance rights go back to the 1700s in France. In the United States, books and maps were first copyrighted under the first federal constitution of 1787, but copyright laws had to be amended in 1831 to include sheet music, which became possible to mass produce with lithography.

Even so, infringement complaints were rarely heeded, and early 19th century songwriters like Stephen Foster (Camptown Races, Beautiful Dreamer, Old Kentucky Home) found it difficult to make a living. Royalty rates were nominal and there was no copyright enforcement, according to Andy Lykens’ Brief History of Copyright.

As New York’s “Tin Pan Alley” became the center of the music industry in the late 19th and early 20th century, concern about copyright and profits emerged as big business.

When Charles K. Harris’ 1891 song “After The Ball” sold over five million copies of sheet music, without copyright protection, the music industry demanded reform of copyright laws. One proposal was the 1895 Treloar Copyright Bill, which would have changed the term of copyright for published music from 24 to 40 years, renewable for an additional 20 instead of 14 years. The failure of the bill was largely due to a proposed mandate for US printing of foreign songs with US copyrights. In other words, if a French song publisher wanted a US copyright, the sheet music had to be printed in the US.

A second attempt at copyright reform DID pass, on January 6, 1897. The new law assessed damages in case of unauthorized public performance of a copyrighted dramatic or musical composition, and imprisonment if the unlawful performance “be willful and for profit.”

But what is a performance? The definition was relatively straightforward in 1897, when all music performances took place in theaters and owners of songs would take a percentage of the box office receipts. But ten years later, as Tin Pan Alley was entering its heyday, it became harder to define a performance. New technologies like the automatic“player” piano and phonographic recording were making music performances possible outside the theater. And commercial radio broadcasting, another performance venue, was on the horizon.

In 1908, the courts did not want to include these new venues under copyright protection. Player pianos did not infringe on music copyrights because they were simply mechanical reproductions, and not actual performances, according to the US Supreme Court in White-Smith Music Publishing Co. v Apollo, 1908.

But songwriters and piano companies rebelled, and Congress supported musicians the next year with the 1909 Copyright Act that included all player piano music under a compulsory license. The idea of a compulsory license was that a single company couldn’t get a monopoly over one recording; other musicians or companies could also perform a song legally so long as they paid the fee.

Performing Rights Organizations

For compulsory licensing to work, a new kind of association was created in 1914: The American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers (ASCAP) managed licenses and sold blanket rights to performers.

When radio came along in the 1920s and 30s, ASCAP was able to take advantage of its monopoly over compulsory licensing, raising rates by 448 percent in the 1930s. Then, in 1940, ASCAP announced it would double its rates again, going from 5 percent of overall radio income to 10 percent. Apparently ASCAP was fairly confident, and they had most of the great songwriters of the day from Tin Pan Alley, like Irving Berlin, Otto Harbach, James Weldon Johnson, Jerome Kern and John Philip Sousa.

If there is one ironclad law of mass media, it is that monopolies will be challenged. The two big radio networks, NBC and CBS, formed their own licensing corporation called BMI and boycotted ASCAP. The boycott lasted from January to late October, 1941. ASCAP thought it would win, because its music included 1,250,000 songs. Instead, BMI signed up a new generation of musicians, including blues, jazz, country, folk and (soon) rock and roll.

BMI also made arrangements of public domain music and gave the arrangements to subscribers for free. Old American standards like “I Dream of Jeanne with the Light Brown Hair” were played so often that Time Magazine said Jeanne’s hair had turned grey. (This Boycott Changed American Music, Radio World, May 4, 2015).

ASCAP had to settle the dispute on unfavorable terms with BMI and also with the US Dept. of Justice, which investigated ASCAP for monopolistic practices. To resolve the issues, a consent decree under the Sherman Anti-Trust Act went into effect in 1941.

By the middle of the 1950s, BMI was licensing 80 percent of all the music on the radio. ASCAP charged that BMI had conspired with radio station owners and record executives to foist rock n’ roll on young listeners. ASCAP deplored they “low quality” music, “race” music, sexual license, and juvenile delinquency its said was associated with BMI’s music. These “pop culture” wars had a huge impact on radio and the growth of rock n’ roll. (Altschuler, G., and D. Litwin, “All Shook Up: How Rock n’ Roll Changed America. Oxford. 2003).

“The important point to recognize is that even though these broadcasters were broadcasting something you would call second best, that competition was enough to break, at that time, this legal cartel over access to music,” said Lawrence Lessig in a 2007 TED talk: Laws that Choke Creativity.

Today, music played over the radio, in restaurants and through other performances of music, are covered under compulsory licensing through ASCAP, BMI and SESAC. Another group, Sound Exchange, covers internet streaming performances.

New technology is once again challenging the century-old copyright law, and the response, in 2018, was the passage of the Music Modernization Act (next page) which facilitates music streaming through the internet as well as modernizes licensing payments to artists and copyright holders.

Compulsory licensing & Authors moral rights

In June, 2015, Neil Young objected to Donald Trumps use of his song, “Keep on Rockin’ in the Free World.” Within a few days, Trump relented and said he would not use the song.

Young was attempting to exercise his moral rights as the author of his songs. But US copyright law does not include most instances of moral rights, so Trump could have continued to use the song if he had wanted to. In 2017, the US Copyright Office was considering an expansion of moral rights, due in part to the long line of controversies swirling around the political use of compulsory licensing and authors moral rights. These have included:

-

- Dropkick Murpheys told Republican presidential candidate Scott Walker to stop using their music because “we literally hate you.” (Daily Kos, Jan, 2015.)

-

- Yoko Ono sued producers of a film released in the US in April, 2008 — “Expelled”— for alleged copyright violations. Read the AP article here and the press release from Expelled here. Also, a collection of discussions about Expelled. Also here is the legal brief (or complaint) in the suit.

-

- The 70s rock group Heart objects to Sarah Palin’s use of Barracuda Heart’s songwriters, Ann and Nancy Wilson, released a statement saying that “Sarah Palin’s views and values in no way represent us as American women” and insisted that the McCain-Palin campaign not play their song.

- The 70s rock group Heart objects to Sarah Palin’s use of Barracuda Heart’s songwriters, Ann and Nancy Wilson, released a statement saying that “Sarah Palin’s views and values in no way represent us as American women” and insisted that the McCain-Palin campaign not play their song.

“While copyrights should be respected, artists who abuse copyright to attempt to muzzle politicians’ speech are sacrificing the broader interest for their own feelings and agendas. This kind of conduct is not what copyright is about; copyright law exists to help artists get paid, and politicians who pay for a blanket license to use a song in a campaign are doing exactly what the copyright law says they should. Artists’ copyrights are important, but the vibrancy of our political discourse is absolutely central. If John McCain wants to tell voters that Sarah Palin is a barracuda, and the most effective way to do so is via Heart’s song, then by all means let it play. And if the Wilson sisters want to mock Republican misuse of a feminist anthem, then let them sing from the mountaintops. But let’s keep the courts out of it.” — Christopher Sprigman and Siva Vaidhyanathan (U.Va. profs) 2008 Washington Post op-ed:

The Electronic Frontier Foundation also objected to expansion of the moral rights of authors, giving them more ability to control how their work is used, saying in 2017 that downstream re-interpretation of copyrighted work is amore positive direction for the law.

MUSIC SHARING ( PIRACY )

In a 2009 trial, a Maryland college student named Joel Tenenbaum admitted illegally downloading 3o songs. The jury awarded the RIAA and other music companies $675,000, or $22,500 per song. In May of 2012, a federal appeals court upheld this verdict ! The first appeals court reduced the amount, but in May of 2012, a high level federal appeals court upheld the entire amount. The US Supreme Court denied cert. See Sony v Tenenbaum (wikipedia)

In Sept, 2012, in a case entitled Capital Records v. Thomas an original award of $222,000 for downloading 24 songs was upheld after many twists and turns and appeals and counter-appeals. Following Thomas’ original conviction, The Wall Street Journal’s Law Blog had a few choice comments: “I believe the RIAA has surpassed the IRS and TSA as the most hated organization – at least in some circles. Quite a distinction for a non-government entity.”

Despite these two cases, the RIAA did slow down in prosecution of other cases in the 2009 – 2012 period and came up with a “six strikes” plan that would work in concert with ISPs. This was RIAA’s attempt to be a little more reasonable, although some objected.

Also new are the “copyright trolls” who are making a living through mass lawsuits and demands for settlements. The EFF has information about how to cope with the legal issues involved in these kinds of copyright cases.

The “Stop Online Piracy Act” of 2012 was an attempt to entrench restrictions and rein in copyright scofflaws. It failed after protests in January 2012. Although it never passed, the idea behind SOPA was to enable U.S. law enforcement to bar advertising and payment networks (like PayPal) from working with suspected copyright scofflaws, to order blocks for search engines and ISPs to the websites. The law would have also made unauthorized streaming of copyrighted content illegal with a maximum penalty of five years in prison. The proposed draconian punishments for what is often relatively innocent infringement seemed out of proportion to the spirit of the laws and the idea of equal justice.

Much of the controversy died down when music industry revenues recovered in the mid-2010s. In the illustration to the right, we see the mp3 slump from CD sales (in orange) recovering with the advent of another new technology, streaming services (shown mostly in green).

Much of the controversy died down when music industry revenues recovered in the mid-2010s. In the illustration to the right, we see the mp3 slump from CD sales (in orange) recovering with the advent of another new technology, streaming services (shown mostly in green).

ICONIC SONGS — Happy Birthday … We Shall Overcome … This Land is Your Land

Happy Birthday: Is the Happy Birthday song copyrighted? For decades, the answer was yes, according to Snopes, the internet myth buster. But others thought not, on the basis that the copyright was inappropriate, (For instance, Professor Robert Brauneis of GW Law School, who notes that Justice Bryer’s dissent in Eldred v Ashcroft included a remark that the song is unoriginal and unworthy of copyright protection.)

In July 0f 2015, evidence surfaced that the song was written and published as early as 1922 — and not 1935, as had been claimed by Warner/Chappell. In September, a federal judge ruled that the copyright claim was not valid and that “Happy Birthday” was in the public domain.

Warner / Chappell is affiliated with Time-Warner and had been making about $2 million a year in royalties with “Happy Birthday.” Warner/ Chappell even charged the maker of a documentary about the controversy $1,500 to use the song (which could probably have been used under the fair use doctrine), and it was during the process of creating the documentary that the original publishing date of the song came to light.

The controversy exemplifies an annoying copyright claim over materials that might be considered in the public domain. The initial complaint from the documentary makers, suing Warner/Chappell, is here.

We Shall Overcome: On January 26, 2018, a federal judge placed the copyright for “We Shall Overcome” into the public domain.

The copyright for the iconic song of the civil rights movement, had been placed under copyright in 1960 by a group of musicians, led by folk singer Pete Seger, out of concern that someone else could register it and take it away from the civil rights movement. The copyright was held by Ludlow Music and The Richmond Organization after that, and royalties from the song were donated to the Highlander Research and Education Center in Tennessee through a We Shall Overcome Fund.

In 2017, filmmaker Isaias Gamboa filed suit against Ludlow and Richmond, arguing that the song was far too old to merit copyright protection. Gamboa was being denied the use of the song even though he was working on a documentary about it.

This land is your land: This iconic song by folk singer Woody Guthrie was copyrighted in 1956 and ownership is still disputed.

MUSIC PARODY AND OWNERSHIP ISSUES

Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music 1994 — (Also briefly noted in Section 5.3 laws & cases)— The rap group 2Live Crew performed a song that was Roy Orbison’s 1960s classic “Pretty Woman,” but in the process changed it. The company run by Orbison’s heirs (Acuff-Rose) sued Luther Campbell of 2LiveCrew. The US Supreme Court, said that parodies are protected under the Fair Use doctrine provided that the parody has substantial transformative value. In other words, it must be a true parody, not a cover for making a profit. Campbell’s version did have that value, so he won the suit. The idea here is that artists are protected from performers who merely want to perform their work without permission, but not from people who want to make a serious parody. Under this legal doctrine, Amish Paradise does not violate the copyright of Gangster’s Paradise because parody is protected speech. In this case, Weird Al is making a direct parody of Coolio. (Although its interesting to note that Weird Al went ahead and paid Coolio a licensing fee anyway). But what if the parody is not so direct? These controversies tensions between the free speech rights to parody a work and the rights of artists to protect their work.

-

- Original Roy Orbison Pretty Woman (from a 1987 performance.)

Fogerty v. Fantasy, 1994, John Fogerty and former manager sued each other over copyright when Fogertys new songs sounded somewhat like his old ones whose copyrights were owned by his former manager at Fantasy Records. Fogerty won the right to sing the way he wanted to sing. The US Supreme Court review was also a landmark in recovery of attorneys fees. Fantasy did not want to pay Fogerty’s attorney fee and argued that defendants were not entitled to recover the fees unless a plaintiff was acting in bad faith. The court rejected that argument as a double standard and said judges should treat plaintiffs and defendants alike in exercising discretion about who pays for the lawsuit. But the larger point — that artists have moral rights to their creations — is still in dispute in the U.S.

Bright Tunes Music Corp. v. Harrisongs Music, Ltd. 1976 — Former Beatle George Harrison wrote a song entitled “My Sweet Lord” with a tune that sounded very much like the Chiffon’s song “He’s So Fine.” Harrison admitted that he may have unintentionally infringed on the Chiffon’s Bright Tunes Music copyright, and the court found for Bright Tunes.

Buchwald v. Paramount Pictures, 1990, In the script for Coming to America with actor Eddie Murphy, the studio contracts were alleged to be so unfair as to be inherently invalid. The problem was that writer Art Buchwald got percent of net profits, not of gross profits. Creative accounting meant that there was no net profit. The court found for Buchwald. A similar lawsuit over the script for Forrest Gump was settled out of court.

MORE COPYRIGHT MUSIC CONTROVERSY:

Oct 2013 — The isoHunt search engine deserved to die says a Washington Post columnist. An appeals court’s decision in March, 2013 reinforced the Grokster “inducement” approach to infringement. An article raising questions about the overall trend in law was published in the WSJ on Oct. 1, 2013: Sony or Grokster? Which model will prevail in new cases involving remote storage of video programming?

Led Zepplin “Stairway” trial was dismissed in 2016 but reinstated in 2018 and settled in favor of Led Zepplin in 2020.

Here is Randy Wolfe’s Taurus (0:45) and here is Led Zepplin’s Stairway.

MORE LINKS

To license a song, you register and pay the fee through the Copyright office. The Library of Congress Copyright Office has a guide to compulsory licensing.

Consent decrees — Future of Music Coalition — August, 2016

Parody means “they don’t even have to ask…” Parody clip from “Downfall” movie. (More “Downfall” parodies here.)

More ‘Hitler finds out’ parodies