Demonstrators outside a Baltimore police station April 25, 2015. Defense attorneys argued for a change of venue, saying that there was a “media frenzy” in the pre-trial news coverage.

When a high-profile criminal case is being heard, what is the role of the news media and how can the courts protect the rights of everyone concerned?

This is the question that arises in many cases, such as the 2015 trials of Baltimore police officers involved in the death of Freddy Gray, or the 2000 Pulaski, Va. case of Jeffrey Allen Thomas who was convicted of the murder Tara Rose Munsey.

The question in both cases was whether a change in venue (trial location) could help or hurt defendants, especially since publicity had reached most of the alternative venues anyway. In Baltimore the venue was not changed, and all defendants were either acquitted or not prosecuted. In Pulaski, the venue was not changed, but the case was rather different. Ultimately, the Virginia Supreme Court concluded that the case should have been moved, because of pre-trial publicity, and ordered a new trial. (In a plea bargain, Thomas accepted a life sentence rather than face the death penalty again.)

To understand the issues at stake, we need to understand the origins of the free press – fair trial problem in communications law.

FIRST AMENDMENT: Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

SIXTH AMENDMENT: In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury of the State and district wherein the crime shall have been committed, which district shall have been previously ascertained by law, and to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation; to be confronted with the witnesses against him; to have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favor, and to have the Assistance of Counsel for his defense.

Criminal cases have been tried in an open, public court as long as the English legal system has been in existence. Despite historical exceptions (such as the Star Chamber of Henry VIII), public trials were usually seen as:

” … giving assurance that the proceedings were conducted fairly to all concerned and discouraging perjury, the misconduct of participants, or decisions based on secret bias or partiality…” (Chief Justice Warren Burger in Richmond Newspapers v. Virginia, 1980).

Yet this right to a public trial may also present a serious conflict with a defendant’s Sixth Amendment right to a fair a trial. For example, most experienced journalists have known district attorneys (or Commonwealth attorneys) who built their political careers on high conviction rates as prosecutors. One of their major tactics to ensure that high rate can be leaks to the press that create an adverse climate before a trial, with the idea that potential jurors would already have formed some basic ideas about the guilt of the accused.

Leaks about evidence in upcoming trials are generally acknowledged to be unethical, although some argue that they are highly unethical. In any event, leaks are not unusual. The pressures on journalists under those circumstances are directly contrary to the presumption of innocence. And since the defense is not likely to divulge its strategy, or sometimes not sophisticated enough to understand the publicity game, there are frequent miscarriages of justice.

Journalists and law enforcement personnel need to understand the case law and also the ethics of news coverage in this area.

Conflicts may include:

• Pre-trial publicity

- — News coverage about opinions or items which a judge may exclude from evidence but which may affect the views of jurors.

- — News coverage which may bias a community against a particular defendant, especially prior convictions or a confession which may have been forced.

• Publicity during trials

- — “Meltdown” of credibility of non-telegenic witnesses or other participants under full media coverage.

- — Cameras in courtrooms turning proceedings into entertainment.

Sensational trials in recent decades include:

The OJ Simpson trial — One of most disturbing problems was televised coverage of information that the jury never got to see. TV audiences found it easy to reach conclusions that the jury could not. Other problems included the sale of books and articles by witnesses scheduled to testify at the trial. The more sensational the testimony, the more money a book or article could make.

California tried to make this illegal but the state law was later ruled unconstitutional.

Police on trial for the Rodney King beating in 1992 — It important to realize that the video most Americans saw was cut short — the jury saw more than what was broadcast on TV. Their acquittal of the officers may have had racist overtones, but the reaction (riots in LA) was not based on the full picture of what was going on.

Unlike the O.J.Simpson trial, the jury saw more than the TV audience.

Casey Anthony trial in 2011 — Sensational trial involving the death of a two year old girl in Orlando Florida in 2008. The trial in 2011 resulted in the acquittal of the child’s mother, Casey Marie Anthony. Heavy national media attention led to “gag orders” for defense attorneys in the pre-trial phase and sequestration of jury during the trial. Rather than change the venue, jurors were brought from another venue to the Orlando / Orange County court.

Many other trials are described on University of Missouri prof. Douglas O. Linder’s Famous Trials page.

Constitutional issues – First Amendment versus Sixth Amendment

Bridges v. California, 1941 — Prior restraint of journalists to prevent pretrial coverage is unconstitutional without a “clear and present danger to the administration of justice.”

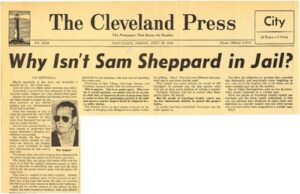

Sheppard v Maxwell, 1966, — Sam Sheppard was convicted of murder in 1954 after his wife was found stabbed to death in their home. He claimed a third person committed the crime, that he had fought with the person and had been knocked out, but no one believed him. Before the trial, newspaper headlines screamed: “Why isn’t Sam Sheppard in Jail?”

Sam Sheppard was convicted of murder in 1954 after his wife was found stabbed to death in their home. He claimed a third person committed the crime, that he had fought with the person and had been knocked out, but no one believed him. Before the trial, newspaper headlines screamed: “Why isn’t Sam Sheppard in Jail?”

During a coroner’s five day inquest, a magistrate dismissed Sheppard’s defense attorney and grilled him in front of a live audience. During the trial, the media took over the courtroom. Sheppard could not whisper in his defense counsel’s ear without being overheard. The courtroom had become a media circus. (For a complete account of the trial and fight to clear Sheppard’s name, see the University of Kentucky law school guide.).

The Supreme Court reversed the conviction in 1966 , saying that Sheppard did not get a fair trial. The court laid out guidelines to help judges keep the courtroom atmosphere impartial. Judges should consider any or all of these remedies, the court said :

- Set rules for in-court conduct by reporters;

- Grant continuance for a later trial or

- Grant a change of venue to keep prospective jury unbiased;

- Admonish jury to ignore publicity, or

- Sequester the jury to insulate them from publicity;

- Issue protective order (gag order) for out of court statements by trial participants

The fallout from Sheppard: Protective (“gag”) orders

Gag orders were originally supposed to involve only officers of the court — defense lawyers, prosecutors and others directly connected with a case. Such orders usually required silence about confessions (which might be inadmissible), rap sheets, or the merits of other evidence. They were perfectly constitutional and in many cases necessary to protect the rights of the accused and the integrity of the courts.

However, some judges took the Sheppard decision as a license for prior restraint of media, saying in effect, don’t print or air certain information about the pending case. About 50 media gag orders were issued between 1967 and 1976. These were especially troubling instances of prior restraint.

* Nebraska Press Association v. Stuart, 1976

— This case involved a media gag order following murder trial testimony. The press was ordered not to mention the existence of a confession. The Supreme Court struck the order down as unconstitutional. Prior restraint, Chief Justice Warren Burger said, has “immediate and irreversible sanction…

” Prior restraints, he said, “are the most serious and least tolerable infringements on First Amendment rights.” Burger didn’t rule out media gag orders altogether, but restricted them to instances where there was:

- Intense and pervasive publicity

- No other alternative measure possible (eg., change of venue, extensive voir dire, etc)

- Certainty that the order will prevent material from reaching potential jurors.

More fallout from Sheppard: closed courtrooms

After Nebraska Press v. Stuart, judges began to see closed courtrooms as the best way to handle pretrial motions or preliminary hearing where evidence is one sided and the defense has to hide its strategy.

Since a pre-trial hearing is not a place to judge guilt or innocence, but rather to hear evidence that may or may not end up in front of jury, this is an area where the release of information is questionable. On the face of it, most people would think that barring pretrial coverage would be a good idea: BUT, the fact is that over 80 percent of the work of the court system goes takes place in pre-trial hearings. Therefore, it was important to challenge the idea of court secrecy. This was done in two cases:

Gannett v. DePasquale 1979 —In this case the Supreme Court allowed pretrial hearings to be closed. The majority of the court noted that the 6th Amendment right of a public trial belongs to defendant and may be waived. In the weeks following the trial, many courtrooms were closed not only to pre-trial motions but also in the full trial sessions.

For example, the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press counted 21 closures of courtrooms in the next month alone. Clearly the Gannett decision was being read as a license to close all courtrooms in any circumstance.

** Richmond Newspapers v. Virginia, 1980 — Quick reversal of Gannett — This case was a reaction to and a clarification of the Gannett decision. The case involved a complicated series of mistrials concerning the murder of a Hanover county motel manager. The court said that “the right to attend criminal trials” was implicit in the guarantees of the First Amendment and that trials could be closed only under extraordinary circumstances. “Without the freedom to attend such trials, which people have exercised for centuries, important aspects of freedom of speech and of the press could be eviscerated,” the court said. In other words, the right to a public trial was a public right and NOT solely a defendant’s right, as the court said in Gannett v. DePasquale.

Riverside Press Enterprise v. Superior Court, 1984 — Six weeks of jury selection was closed, and even records were not made public after the fact. Problem involved privacy of prospective jurors. Burger “Proceedings in secret would frustrate the broad public interest … ” Deeply personal matters might be discussed in chambers during voir dire, but have to be exceptional to not be placed on the record.

Riverside Press Enterprise v. Superior Court, 1986 (Riverside II) — A newspaper protested the closing of a 41-day preliminary hearing of male nurse accused of killing a dozen hospital patients. SC ruled must be open unless there is a substantial probability that an open hearing will prejudice defendant’s right to fair trial and there are no reasonable alternatives. Riverside II had the effect of leaving most pretrial hearings open.

Change of venue

The Thomas murder trial in Radford, VA in 2002 is an example of what happens when venue is not changed under intense publicity. In January, 2000, Tara Rose Munsey, the daughter of a Radford Univesity art teacher, was murdered. Pulaski County resident Jeffrey A. Thomas was charged with first degree murder. His attorneys filed a pretrial motion seeking to change venue, arguing that the “barrage” of publicity surrounding his trial made it impossible to receive a fair trial in Pulaski County.

According to a Virginia Supreme Court decision, Thomas produced over 111 articles appearing in the three newspapers serving the area and video tapes or transcripts of over 188 television reports relating to the crime. One article reported that a search warrant for Thomas’ person and car led to the discovery of a .22 caliber Marlin rifle, “which authorities believe was used in the murder.” Similarly one headline stated “Police tie bullet to murder suspect” when in fact the bullets found could not be linked to Thomas, according to the state Supreme Court decision.

Attorneys for Thomas asked for a change of venue, but the trial judge was not persuaded. Thomas was given a death sentence in June, 2001. His attorneys filed an appeal and on March 2, the Virginia Supreme Court overturned the death sentence, saying that news reports had poisoned the jury pool. The decision was unanimous, and was the fourth death sentence that had been overturned that year.

“The tenor of the publicity went beyond dispassionate reporting of the events surrounding the crime, the victim, and the accused, even though it did not declare the accused guilty or call for his conviction or for a specific punishment,” the court said in striking down the sentence. “Further, the inaccuracies are additional persuasive evidence of the existence and development of community prejudice against Thomas.” The court remanded the case for a second trial, at which point Thomas pled guilty to avoid the death penalty.

It’s important to note that Thomas was sentenced to life imprisonment. He did not escape justice simple because the courts found that there were problems with the first trial. An important additional factor in the life sentence included the plea by Munsey’s mother, through her church, against the death penalty for the murderer of her daughter on moral and practical grounds.

Public access

Despite the Richmond Newspapers case of 1980, Virginia courts are still barring the public, and the news media, according to this September 2021 editorial in the Norfolk Virginian Pilot newspaper.

Criminal cases should be open to the public, including members of the news media, unless there is clear and compelling evidence that it would violate the constitutional rights of the accused. Yet, in the case involving a man charged with killing a Newport News police officer, those petitioning to bar reporters from the court appear to be doing so as a matter of convenience, not of necessity.

ETHICAL DIMENSIONS OF FREE PRESS / FAIR TRIAL ISSUE

It’s important to note that in many states, joint commissions of the press and bar associations have issued voluntary guidelines for ethical behavior by members of the media and legal professions when pre-trial publicity issues come up. Washington state, for example, has a bench-bar press committee, to examine ethical dimensions to press coverge of trials.

The News Media Handbook on Virginia Law and Courts, published by the Virginia Bar Association, the Virginia Press Association, and the Virginia Association of Broadcasters, had this to say about Free Press Fair Trial issues:

Principles:

1. We respect the co-equal rights of a free press and fair trial.

2. The public is entitled to as much information as possible about the administration of justice to the extent that such information does not impair the ends of justice or the rights of citizens as individuals.

3. Accused persons are entitled to be judged in an atmosphere free from passion,

prejudice and sensationalism.

4. The responsibility for assuring a fair trial rest primarily with the judge who has the power to preserve order in the court and the duty to use all means available to see that justice is done. All news media are equally responsible

for objectivity and accuracy.

5. Decisions about handling the news rest with editors and news directors, but

in the exercise of news judgments based on the public’s interest the editor or news director should remember that:

- An accused person is presumed innocent until found guilty

- Readers, listeners and viewers are potential jurors

- No person’s reputation should be injured needlessly

6. No lawyer should exploit any medium of public information to enhance his side of a pending case, but this should not be construed as limiting the public prosecutor’s obligation to make available information to which the public is entitled.

7. The media, the bar, and law enforcement agencies should cooperate in assuring a free flow of information but should exercise responsibility and discretion when it appears probable that public disclosure of information in prosecutions might prevent a fair trial or jeopardize justice, especially just before a trial.

Guidelines

1. The following information generally should be made available for publication at or immediately after an arrest:

- Accused person’s name, age, residence, employment, family status and other factual background information.

- Substance or text of the charge, such as complaint, indictment, or information and, where appropriate, the identity of the complainant and/or victim.

- Identity of the investigating and arresting agency or officer and the length of the investigation.

- Circumstances of arrest, including time and place of arrest, resistance, pursuit, possession and use of weapons and description of items seized.

- If appropriate, fact that the accused denies the charge

2. The release of photographs or the taking of photographs of the accused at or immediately after an arrest should not necessarily be restricted by defense attorneys.

3. If an arrest has not been made, it is proper to disclose such information as may be necessary to enlist public assistance in apprehending fugitives from justice. Such information may include photographs, descriptions, and other factual background information, including records of prior arrests and convictions. However, care should be exercised not to publish information which might be prejudicial at a possible trial.

4. The release and publication of certain types of information may tend to be prejudicial without serving a significant function of law enforcement or public interest. Therefore, all concerned should weigh carefully against pertinent circumstances the pre-trial disclosure of the following information, which is normally prejudicial to the rights of the accused:

- Statements as to the character or reputation of an accused person or prospective witness.

- Admissions, confessions or the contents of a statement or alibis attributable to the accused, or his refusal to make a statement, except

his denial of the charge. - The performance or results of examinations or tests or the refusal or failure of an accused to take such an examination or test;

- Statements concerning the credibility or anticipated testimony of prospective witnesses.

- The possibility of a plea of guilty to the offense charged or to a lesser offense, or other disposition.

- Opinions concerning evidence or argument in the case, whether or not it is anticipated that such evidence or argument will be used at trial.

- Prior criminal charges and convictions although they are usually matters of public record. Their publication may be particularly prejudicial just before a trial.

5. When a trial has begun, the news media may report anything done or said in open court. The news media should consider very carefully, however, publication of any matter or statements excluded from evidence outside the presence of the jury because this type of information is highly prejudicial and, if it reaches the jury, could result in a mistrial.

6. Law enforcement and court personnel should not encourage or discourage the photographing or televising of defendants in public places outside the courtroom.

More Links

- The Sheppard Trial, from Doug Linder’s Famous Trials website.

- Encyclopedia Brittanica video on the Sheppard trial.

- Sam Reese Sheppard’s web site on his father’s trial.

- PBS web site about the Sheppard Trial.

- CourtTV covers sensational trials routinely.

- Pre-trial Publicity prevents a Fair Trial in the USA, by R. Standler.

- Source protection in gruesome Illinois murder case. Oct. 2013.

- Jordan Gross on the history of Free Press / Fair Trial issues, 2012

- Australian courts gag orders around child abuse charges in Jan. 2019 and in Columbia Journalism Review