Sherrod v Brietbart, 2015

Sometimes a photo or a video clip is edited or captioned in a way that leads to a totally false conclusion. Although a video may be truthful in the sense that it depicts one slice of reality, there are times when editing creates a deceptive context or puts a person in a “false light,” which is one of the five types of privacy torts. (A tort is a wrong that can be addressed by a lawsuit in civil court).

Consider the case of Shirley Sherrod and the ethically challenged Brietbart news organization. In 2010 Sherrod gave a speech on her experiences working for the USDA in rural development to a regional NAACP chapter. A video clip of the speech became the subject of a national controversy because it seemed to show racism by African Americans against European Americans. In the video, Sherrod talked about a moment when she was tempted to exclude a few white farmers from USDA benefits. That is the only part of the video clip that was distributed by right-wing web publisher Andrew Brietbart.

But there was more to the speech. It was true, Sherrod did talk about being tempted to exclude white people, but what Brietbart excluded was that she said that she could not, in good conscience, deny them the benefits they were due. She did perform her duty, without bias, as a USDA official. So Brietbart’s editing of the video led to a conclusion that was directly contrary to the meaning and context of the whole speech.

Sherrod filed a defamation lawsuit Feb. 11, 2011 in a US District Court which was essentially a “false light” privacy claim. In December, 2015, Sherrod and the Brietbart estate settled the suit. By that time, the Brietbart estate had plenty of money to settle with.

False light is one of five areas of privacy law, and it’s very much like libel. The traditional four are false light, misappropriation, intrusion, and publication of private facts. Some states, such as Virginia, also have a privacy tort for “intentional infliction of emotional distress.”

privacy law in the US

Privacy laws are an attempt to distinguish between the public sphere of life and the private personal sphere. Unlike defamation laws, privacy laws tend to vary from state to state and from situation to situation. But like defamation, privacy law distinguishes between public figures and private people. A lawsuit over defamatory truth about a private person is more likely to be successful, even though private people in these situations are often unwilling public figures, such as in the Sipple or Howard cases (below).

Privacy rights may involve both personal rights, such as the right to a good reputation, and property rights, such as the right to prohibit trespassing or to control the way your own picture is used by others for advertising. One important difference here is that personal rights are attached to a person’s life and do not continue after death. (The right to a good reputation under libel law is also personal). Property rights can be sold or inherited, and in fact, many misappropriation cases involve the estates of dead celebrities.

Digital privacy is an emerging aspect of privacy law involves the way social media companies collect private facts and (arguably) misappropriate them through sale to advertisers.

History of privacy laws

The call for privacy laws in the US began with an 1890 Harvard Law Review article by Louis Brandeis (who later became a US Supreme Court judge). Brandeis noted that England and France had a variety of laws protecting privacy and thought that the US should adopt similar laws. He argued that a right to privacy does not prohibit publication of matters in the public interest, but should protect private people from becoming “victims of journalistic enterprise.” Although truth would be a defense in libel, Brandeis wrote, truth or falsehood is not the issue in the right of privacy, which “implies the right not merely to prevent inaccurate portrayal of private life, but to prevent its being depicted at all.”

This privacy principle was already part of common law, Brandeis argued, but had become more urgent with the intrusiveness of the yellow press and the arrival of halftone technology that allowed photos to be printed in the 1890s.

An early example of the way halftones challenged the law involved a 1902 case, Roberson v. Rochester Folding Box Co. The company used a picture of Abigail Roberson on a box of baking flour without her permission.

An early example of the way halftones challenged the law involved a 1902 case, Roberson v. Rochester Folding Box Co. The company used a picture of Abigail Roberson on a box of baking flour without her permission.

In a lawsuit, the family claimed the incident caused Ms. Roberson severe embarrassment and humiliation, but according to the N.Y. Court of Appeals, there was no law against the use of her likeness in advertising. Concern over what people saw as the theft of Ms. Roberson’s likeness for commercial reasons led to the passage of new laws against “misappropriation” in New York. A similar case occurred in Georgia two years later when New England Life Insurance Co. used a person’s name to sell insurance without permission. (Pavesich v. New England Life, 1905). In that case, the Georgia supreme court said there was a common law right of privacy that had been violated by the commercial use of someone’s identity.

More of the kind of protection Brandies sought for private people began to emerge in some state laws and with the increasing concern for personal rights in the 1960s, for example, with a Connecticut case in which distribution of contraceptive information by a doctor to a married couple was seen as protected by the couple’s privacy rights. Personal privacy was also a major point of law in Roe v. Wade, the Supreme Court said that right extended to the ability to decide when to conceive children or even to have an abortion. (These cases are not media – related, so we will not go into them here).

It’s important to note that the courts have generally defended the freedom of the news media to publish information of public importance. Even in cases where private people are thrust against their will into the public spotlight, such as Robin Howard and Oliver Sipple (below), invasion of privacy suits are often decided in favor of the news media.

Ethics and privacy law

Sometimes in privacy law, ethics and the law collide. For example, the professional ethical codes of the Society of Professional Journalists, the American Advertising Federation and the Public Relations Society of America emphasize minimizing harm and respecting privacy.

One important privacy case involved the identification of a sexual assault victim by a Georgia broadcaster, based on information lawfully obtained from public records. In Cox v Cohn, the court said that disclosing the victim’s name wasn’t an illegal invasion of privacy.

However, in this and many similar cases, it is highly unethical to disclose the names of victims or witnesses to crime unless they want to come forward publicly. (See, for example, the SPJ code, which says that journalists should minimize harm. Identifying crime victims or witnesses to crime in the media can be a serious breech of professional ethics.).

Defenses against privacy lawsuits:

- Newsworthiness, or public interest (for editorial content, mostly in misappropriation and false light cases)

- Public record, a Constitutional defense similar to privilege (especially publication of private facts cases, in regard to revealing names of private people involved with the courts or police)

- Consent of private individual involved, for example, a signed release of a model to allow commercial use of name, image or likeness. Note that consent is not needed for casual background / bystanders in news or public affairs video or photography.

Types of privacy lawsuits

Privacy law consists of four main types of torts. A fifth area has been included in recent years:

- False Light — This is similar to libel. It often covers indirect libel, sometimes in photos or badly edited video. Usually the Sullivan standard applies (knowledge of falsity or reckless disregard for the truth) along with the standard holding that false light is something highly offensive to a reasonable person.

- Publication of Private Facts or unreasonable revelation of private facts that may be true but nevertheless embarrassing to private people.

- Intrusion on a person’s right to seclusion and personal privacy; Media cases usually involve physical intrusion by news media, often with cameras or recording devices, into the lives of celebrities and private people. Surveillance was an issue in the News of the World scandals of 2011 – 2025. Digital surveillance by social media companies may also fall under this privacy tort, but surveillance by government agencies involves Fourth Amendment rights.

- Misappropriation is the commercial misuse of a person’s name, image, or likeness (picture). This area of law can overlap or be similar to trademark and copyright.

- For private people, misappropriation is sometimes called “commercialization”

- For celebrities, misappropriation cases involve a “right of publicity”

- Intentional infliction of emotional distress — In some states, such as Virginia, intentional infliction of emotional distress, is sometimes used in place of false light, intrusion and publication of private facts. However, as the courts noted in Flynt v Falwell, this is not a substitute for defamation.

1. False light

False light is a close cousin to libel and it involves questions of reputation and statements that might be highly offensive to a reasonable person. A false light plaintiff has to satisfy the Sullivan test for actual malice.

Sherrod v Brietbart, 2010 — USDA official fired after a damaging part of a video surfaces; a few days later, it turns out that the damaging part was contradicted by the full video. The suit was settled in 2015 with unspecified damages paid to Sherrod.

People’s Bank and Nellie Mitchell v. Globe International Publishing, 1992 — When photos of an elderly Arkansas woman delivering newspapers were published in the National Examiner in 1980, Nellie Mitchell did not object. Ten years later, when the same photos ran next to a fictional story about an elderly woman who had to quit her paper route because she became pregnant, Mitchell’s estate (the People’s Bank) sued on behalf of Mitchell under false light and won. (Also see Encyclopedia of Arkansas).

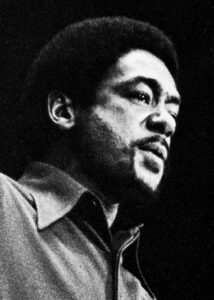

Bobby Seale

Bobby Seale v. Gramercy Pictures Inc., 1998 — Bobby Seale was a famous Black Panther in the 1960s and the Panthers were the subject of a Gramercy Pictures 1990s documentary video. Seale objected to the video’s characterization of a conversation with another Panther (Eldridge Cleaver) and sued unsuccessfully under the legal theory of false light. Seale was a public figure, so the court applied the Sullivan actual malice standard. Gramercy Pictures won.

Cantrell v. Forest City Publishing Co 1974 — A reporter pretended to have interviewed widow of man killed in a West Virginia bridge collapse, describing her face and talking about her courage in refusing charity, and yet had never bothered to interview her. The court said he had acted with malice, that is, knowingly publishing something false.

Time v. Hill 1967, Time magazine published a story about a play based on a true story in which prison escapees had taken a family hostage. The events had occurred some 15 years beforehand. In the story there were a few inaccuracies, such as the idea that hostage takers had roughed up the Hill family and made sexual slurs. The family felt their privacy had been invaded. Judge Brennan said that “breathing room” for the First Amendment meant the need to tolerate some level of inaccuracy as much in reporting on a drama as in other political reporting. The family would have to prove actual malice, thus their status was something like that of an involuntary public figure in a libel suit.

2. Publication of private facts

Like false light, lawsuits over publication of private facts involve the personal right of privacy. There are four elements to a PPF lawsuit:

1. Public Disclosure: Facts are published, broadcast, or disseminated in some way.

2. Private Fact: The facts disclosed must be private and not generally known. It usually can’t involve facts that have already been made public.

3. Offensive to a Reasonable Person: The facts must be offensive to a reasonable person of ordinary sensibilities. Just a photo of a person slipping on a banana peel on a sidewalk might be a little embarrassing, but it is not enough. Disclosure of a loathsome disease, if true, would probably be offensive. Publication of facts concerning a private person’s financial records, medical information or domestic difficulties may be embarrassing enough to cause damages.

4. Not Newsworthy: The facts disclosed must not be newsworthy or involve matters of public interest.

(See Reporter’s Committee for Freedom of the Press briefing on PPF)

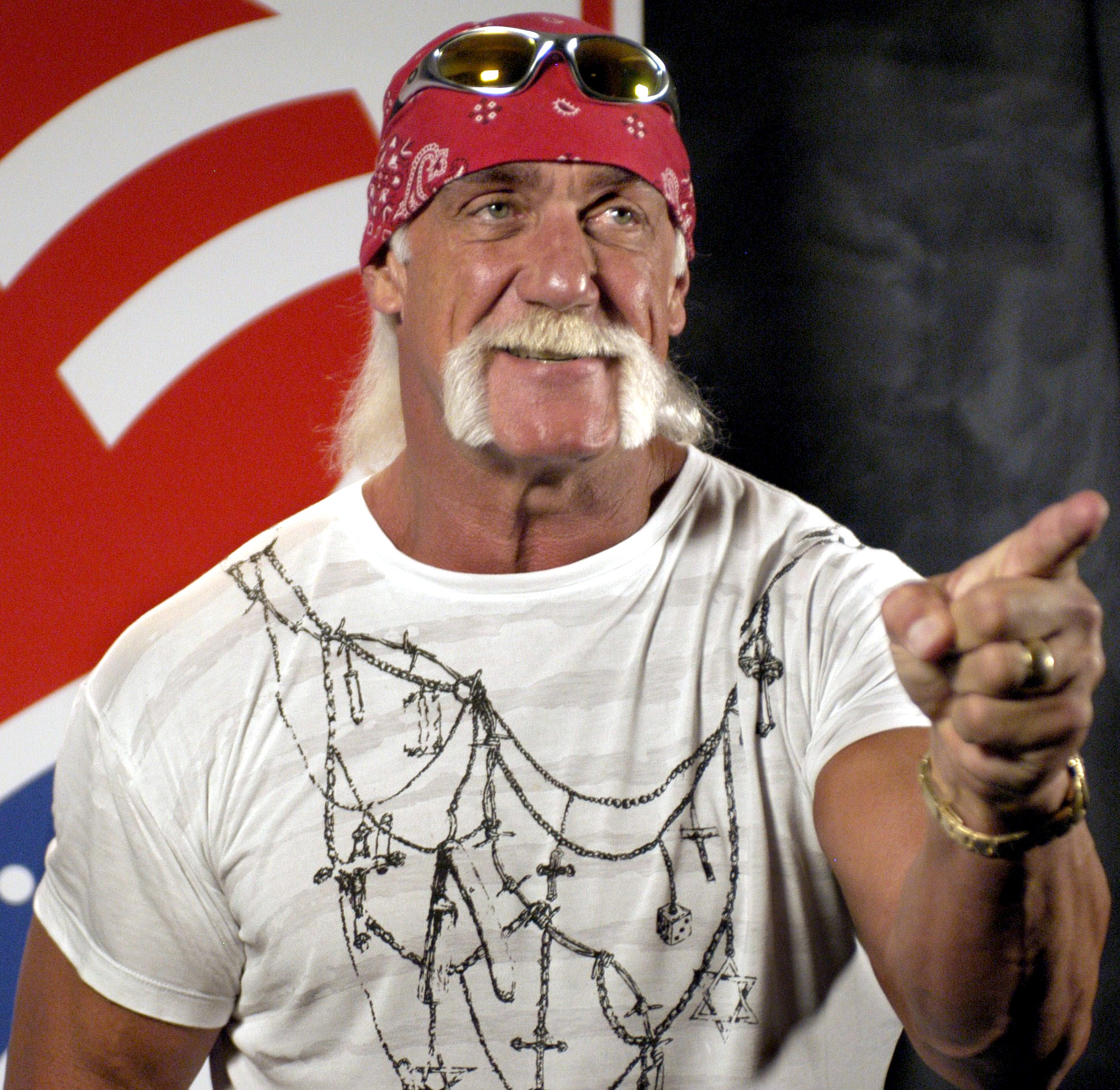

** Bollea v. Gawker, 2016 — When Gawker magazine posted sex videos of Hulk Hogan (Terry Gene Bollea) with a friend’s wife, Bollea filed suit in a Florida state court for invasion of privacy (intrusion, publication of private facts and misappropriation) along with intentional infliction of emotional distress. To win, Bollea had to show that this was truthful information, that a reasonable person would find it highly offensive, and that it did not involve a legitimate public concern. (See The Law Behind the Hulk Hogan verdict. Also see the New York Times story. and a more recent Talking Points Memo article about Gawker as the “Case of the Century.”

A jury found the release of the videos highly offensive, and even though Bollea is a public figure, awarded him $140 million in March, 2016. A month later, when two appeals were denied, Gawker magazine went into bankruptcy. The magazine did not have the money for appeals. And it seemed clear that Gawker had crossed a line; courts in previous cases involving sex tapes and stars like Pamela Anderson and Natalee Holloway ruled that writing about such tapes was not an invasion of privacy, but showing the tapes was an invasion of privacy. In retrospect, the case had a chilling effect on the press, even with cases that were more in service to the public interest and less to the prurient interest .

Melvin v. Reid, 1931— A movie called the “Red Kimona,” written and produced by Dorothy Davenport Reid, came out in 1925. It presented what it said was the true story of a former prostitute Gabrielle Darley who was charged with murder in New Orleans and found innocent. In 1918, Darley married a high society figure from St. Louis, Mr. Bernard Melvin and she abandoned her old life. When the Red Kimona movie came out in 1925, Mrs. Melvin (Darley) sued for $50,000 and won in California court.

The movie producers argued that all the facts of the case were true and open in court records. The court said: “Any person living a life of rectitude has that right to happiness which includes a freedom from unnecessary attacks on his character, social standing, or reputation.”

Today, this case would have been decided rather differently. Information in open court records is privileged, as noted in Cox v Cohn and Smith v Daily Mail cases. However, the idea that private people deserve a chance to be rehabilitated is part of the debate over the “right to be forgotten.”

Sidis v. F.R. Publishing,1940 — A celebrated mathematical genius and Harvard grad at age 16, William Sidis disappeared from public view but was profiled in a New Yorker magazine wrote an article under the headline: “Where Are They Now? April Fool!”

Sidis sued for invasion of privacy but lost. NY federal appeals court said someone who had become a celebrity even involuntarily could not avoid all publicity later on. The key question was newsworthiness or public interest. “Regrettably or not, the misfortunes and frailties of neighbors and public figures are subjects of considerable interest and discussion to the rest of the population.”

** Cox. v. Cohn, 1975, The identification of a sexual assault victim by a Georgia broadcaster from information lawfully obtained from public records wasn’t invasion of privacy, the courts said. (However, identifying sexual assault victims in the media, without consent, is usually a serious breech of ethics). Florida Star v B.J.F. (1989) is a similar case where truthful, lawfully obtained information was not considered to be invasive.

*Smith v. Daily Mail, 1979. A school shooting in Charleston, W.Va. in 1978 led to the arrest of a 14 year old boy. Under state law, juvenile suspects cannot be named in newspaper accounts. While it is permissible for a state to keep information about juvenile subjects secret, the court said, but if the media obtain the information lawfully, they should be able to publish without fear of prosecution. According to the ACLU brief:

“The question for decision is not whether the public’s interest in knowing the name of a juvenile defendant outweighs the harm which may result from revealing it. There are many situations and this may well be one in which the prudent newspaper editor would conclude that it is better not to publish. But the First Amendment does not protect only the prudent. Rather, it guarantees that in all but the most compelling circumstances each editor has the right to decide whether particular information in his possession should be published, at least where the information is lawfully acquired. The information at issue here was neither obscene nor untruthful. It concerned a matter of public importance. It was not secret. It was acquired by lawful means. It is precisely the sort of information to which First Amendment values most clearly attach.”

* Howard v. Des Moines Register, 1979 — Robbin Woody Howard was identified as a victim of forced sterilization in county mental facility in an article about the tragic legacy of coercive eugenics in the US. She sued for invasion of privacy, but the Iowa state supreme court said the news article was a good example of investigative journalism and was the subject of public interest. This is an example of the leeway courts allow legitimate news articles.

**Sipple v. Chronicle Publishing, 1984. A bystander named Oliver Sipple prevented the assassination of then-president Gerald Ford outside a San Francisco hotel in 1975. Shortly afterwards, Sipple’s past as a gay activist became part of the story of his heroism. He sued the San Francisco Chronicle for revealing details of his private life, but lost because he had become a public figure and questions about his character were deemed newsworthy. The court said: “There can be no privacy with respect to a matter which is already public or which has previously become part of the ‘public domain.’ Once the information is released, unlike a physical object, it cannot be recaptured and sealed.” A 2021 RadioLab podcast about the case describes the way Sipple “paid dearly” for his heroism.

**Sipple v. Chronicle Publishing, 1984. A bystander named Oliver Sipple prevented the assassination of then-president Gerald Ford outside a San Francisco hotel in 1975. Shortly afterwards, Sipple’s past as a gay activist became part of the story of his heroism. He sued the San Francisco Chronicle for revealing details of his private life, but lost because he had become a public figure and questions about his character were deemed newsworthy. The court said: “There can be no privacy with respect to a matter which is already public or which has previously become part of the ‘public domain.’ Once the information is released, unlike a physical object, it cannot be recaptured and sealed.” A 2021 RadioLab podcast about the case describes the way Sipple “paid dearly” for his heroism.

Anonymous comments

A judge in Cleveland OH filed suit for $50 million against the Cleveland Plain Dealer newspaper in April, 2010 for invasion of privacy after the paper revealed that she (or someone in her family) made anonymous comments about a lawyer appearing before her in a legal case. The case came at a time when newspapers were rethinking the policy of allowing anonymous online comments.

3. Intrusion

- Trespass – entering private property without consent or getting too close with cameras

- Surveillance – bugging, hidden cameras, hacking

- Misrepresentation and undercover reporting

Intrusion cases often involve media news-gathering, when hidden cameras or deception are involved. To win an intrusion suit, a plaintiff must prove that the media acted in a way that a reasonable person would find highly offensive. This is one of the most difficult areas to define since there is often no absolute expectation of privacy. There have been a number of instances of ethical trespass or deceptions when reporters have gone undercover to investigate matters of public interest. Nelly Bly’s investigation of a New York City women’s asylum in 1888, or John Howard Griffin’s undercover work for the 1961 book “Black Like Me” are examples.

Trespass

The law involving media trespass includes:

Galella v. Onassis, 1972 — Jackie Kennedy Onassis obtained a court injunction against New York paparazzi photographer Ron Galella, forcing him to stay 50 yards (later changed to 25 feet) away from Onassis. He was found guilty of breaking this order four times and faced seven years in jail and a US$120,000 fine; later settling for a US$10,000 fine and surrendering his rights to photograph Jackie and her children.

Arnold Schwarzenegger, actor and governor of California (2003 – 2011) was involved in constant conflict with rude & aggressive paparazzi. One result was a 2009 California law making it easier to sue media organizations that published improperly obtained photos.

Wilson v. Layne, 1999 — Also important is the case that banned reporter “ride-alongs” with police. In this case, police invited a Washington Post photographer to accompany them on a search warrant raid in 1992. Police were looking for the son of a Montgomery County, Maryland couple, but instead subdued the couple in the early morning hours. After being photographed in this more or less embarrassing situation, the couple sued for invasion of privacy. The Supreme Court said that the police could not have predicted what course Constitutional law would take in this complex situation and were therefore not liable for damages. But the court also said that from that point forward ride-alongs could violate privacy

Surveillance

Dietmann v. Time, 1971, Life magazine Crackdown on Quackeryarticle, court ruled that indeed use of hidden electronic recording equipment by news media was invasion of privacy.

Bartnicki v. Vopper, 2001 — A radio station DJ played a recording of an illegally intercepted cell phone call. The radio DJ said it was newsworthy and the court agreed that matters of public interest have a First Amendment shield even if the information was obtained illegally by a third party. Jean v. Mass. State Police (2007) also held that the First Amendment protects the news media’s disclosure of an illegally obtained video recording if it’s of significant public concern.

News of the World scandal 2011 – 2025 was a series of revelations involving the illegal wiretapping, hacking and surveillance of royals and celebrities in the UK. It resulted in the closure of the News of the World newspaper and the arrests of about a dozen of its editors. An inquiry by the Leveson Commission found that the existing Press Complaints Commission was too weak. It recommended a new independent oversight commission. The final part of the saga ended with the 2025 settlement of a libel case brought by UK Prince Harry.

Deception

ABC v Food Lion, 1997 — An appeals court declined to use a First Amendment analysis, and instead let trespassing charges stand, in a case involving broadcast reporters who got jobs at a Food Lion store and took video of bad practices behind the meat counter.

4. Misappropriation

Also called commercialization, these cases usually involve private people whose names, likenesses or other identifying characteristics were used without their permission. Virginia state law recognizes “misappropriation”

Roberson v. Rochester Folding Box Co., 1902 — (mentioned above); this case came before state laws against misappropriation

Charlie Chaplin v Amador, 1923 — Silent film star Charlie Chaplin successfully sued a lookalike named “Charlie Aplin ” in a 1923 case. The problem was the attempt at deception, said the court.

Charlie Chaplin v Amador, 1923 — Silent film star Charlie Chaplin successfully sued a lookalike named “Charlie Aplin ” in a 1923 case. The problem was the attempt at deception, said the court.

Polydoros v. Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp., 1997 — Michael Polydoros was a childhood friend of David Evans. When Evans wrote the movieThe Sandlot, Polydoros claimed that he was the fictional character Michael “Squints” Palledorous in the movie and sued for misappropriation of identity and invasion of privacy. (Further commentary by Rochelle Wilcox) The courts sided with Evans, noting: “It is generally understood that novels are written out of the background and experiences of the novelist. The characters portrayed are fictional, but very often they grow out of real persons the author has met or observed …

Frazier v. Boomsma, 2007 — Anti-war activist Dan Frazier used the names of 3,461 soldiers who had died in Iraq as the background of a t-shirt with “Bush Lied” in large type. Although some states prohibit the use of soldiers names for commercial purposes, a federal court held that this was protected political expression.

Schwarzenegger v. Ohio Discount Merchandise, 2004 — Although settled out of court, this case over a “bobbin” doll raises an interesting issue. When a celebrity becomes a politician, do efforts to control publicity infringe on the First Amendment?

Carson v. Here’s Johnny,1976 — Carson sued after a portable toilet manufacturer used his introductory slogan, “Here’s Johnny” to advertise his toilets.

Right of publicity

Everyone has a right of publicity to protect their names, images, and likenesses (NIL) from unfair commercial use. This even includes their wardrobes, singing styles or other identifying characteristics of celebrities. However, the law varies quite a bit from state to state.

Singers Tom Waits, Bette Middler and many others have sued when sound-alike songs were used without their permission. The use of look-alike actors can also be a problem, for example, in a case involving a Woody Allen look-alike used to advertise a video store.

The Middler v. Ford Motor Co. (9th Cir. 1988) involved singer Bette Midler. She refused to do an ad for Ford, and the ad agency hired one of her backup singers to sing one of Middler’s songs in her voice. Middler won the case. In another similar case, Vanna White v. Samsung Electronics of America, Inc., the electronics manufacturer had a blonde robot flipping cards on a game show. White said it was her likeness and won the suit.

Zacchini v. Scripps Howard Broadcasting 1977 — A TV station broadcast a “human cannonball’s” entire act, against his objections, and the US Supreme Court rejected the TV station’s newsworthyness defense. The court said the broadcast deprived him of the economic value of his performance. This ruling is similar to copyright rulings where partial excerpts for reviews might be permitted under fair use, but a complete reprinting or rebroadcasting of some material would be copyright infringement.

4.3 Student athletes and NILs

College sports figures, as of 2021, have the right to make money to endorse products (through licensing of their NILs) in the same way that professional athletes do. Many colleges now use licensing agencies such as Student Athlete NIL to organize the sale of these endorsements.

In 2024, the NCAA agreed to further changes and to pay damages to athletes who lost out financially due to its previous rules. New rules took effect August 1, 2024, allowing athletes to pursue NIL opportunities without limitations.

5. intentional infliction of emotional distress

Virginia and some other states also recognize a tort called “intentional infliction of emotional distress” (IIED).

The state supreme court first recognized the tort of intentional infliction of emotional distress in Womack v. Eldridge, 215 Va. 338, (1974). The court said that a plaintiff may recover damages for emotional distress resulting from a non-tactile tort if he alleges and proves by clear and convincing evidence that: (1) the wrongdoer’s conduct is intentional or reckless; (2) the conduct is outrageous and intolerable; (3) the wrongful conduct and the emotional distress are causally connected; and (4) the resulting distress is severe. (As noted in McDermott v. Reynolds, 2000)

However, IIED is not a substitute for libel or false light privacy torts. Just because someone suffered from criticism does not mean that they can recover damages.

So, for example, the US Supreme Court rejected the idea of using intentional infliction in place of libel in Hustler Magazine and Flynt v Falwell, 1988. The oral argument in the case was reproduced in the 1996 movie, The People vs Larry Flynt. Its a good example of what the Supreme Court looks like during an oral argument.