Most nations have advertising regulations of one sort or another, and they are often drawn from international standards organizations such as the International Chamber of Commerce or the International Council for Advertising Self-regulation. Europe has the European Advertising Standards Alliance.

These codes exist (according to the ICAS) “to ensure that advertisements and all forms of marketing communications are prepared with a due sense of social responsibility.” Among the basic principles are that ads should be legal, decent, honest and truthful and observe principles of fair competition.

In one obvious instance of consumer fraud, and Australian clothing company claimed in 2021 an “anti-virus” effect for its “activewear.” Lorna Jane claimed its sprayed-on shield “would eliminate and repel covid and other viruses, bacteria and fungus.” The company was fined $3.7 million by Australian authorities for making false claims.

Advertising regulation in Europe is far more paternalistic, yet advertising graphics tend to be more sexually explicit than in the United States. For example, ads for tobacco and alcohol are tightly regulated in Europe, and yet ads with nudity or suggestive themes are not considered as offensive to European tastes.

UK advertising regulation was assumed by the Advertising Standards Authority, which consolidated advertising regulatory authority from television, radio, and print commissions in 1955. A set of codes, developed soon afterwards, is described as a mixture of self-regulation for non-broadcast advertising and co-regulation for broadcast advertising. Like US advertising laws, ads cannot be misleading or cause “physical, mental, moral or social harm to persons under the age of 18.”

Controversies about advertising in Europe often revolve around attempts to maintain traditions amid an increasing internationalization of both advertising and language. For example, French advertising laws discriminated against non-French products until around 1980, when Scotch whiskey manufacturers sued France in the European Court of Justice. The EU has rules to support traditionally located products, for example roquefort cheese and champaign in France, feta cheese in Greece, or Melton Mowbray pork pies in Leicestershire, UK. (The Cato Institute, a conservative US policy group, questioned these regulations in a 2016 report. Yet the US also has Vidalia (Georgia) sweet onions, Florida orange juice, Tennessee bourbon, and Idaho potatoes under certification marks.)

Political advertising is heavily regulated in Europe, not only in terms of spending limits but also limiting ads to several months before a general election. The venue for advertising political party broadcasts is also controlled.

New regulations in Europe will require political advertising to be clearly labelled as such and include information such as who paid for it and how much. Political targeting and amplification techniques would need to be explained publicly in unprecedented detail and, would be banned when using sensitive personal data without explicit consent of the individual.

But standardizing regulations is still a work in progress, according to this European Union / Council of Europe report in 2021.

Climate change and advertising

Sometimes restrictions on political advertising hold back general issue debates. For example, Canada has strict regulations on partisan advertising during the election period, whether they be from candidates, parties or third-party organizations. Environmental organization cried foul in 2019. Elections Canada told environmental groups that because one candidate says there is no problem with climate change, any ad urging action on climate change could be considered “issue advertising” during the election period, and therefore restricted.

Steven Cornish of the David Suzuki Foundation says it is “absolutely ludicrous” that charities are barred from advocacy work on climate change during the election just because one of the party’s platforms denies it is an issue. “We’re talking here about someone’s opinion overruling scientific consensus around the need to adapt to climate change,” he said. (BBC – Aug. 21, 2019).

Ethical pressure on major advertising and public relations firms is also a factor

in environmental debates. (Reuters, Jan 19 2022).

in environmental debates. (Reuters, Jan 19 2022).

Infant formula & Nestle Corp.

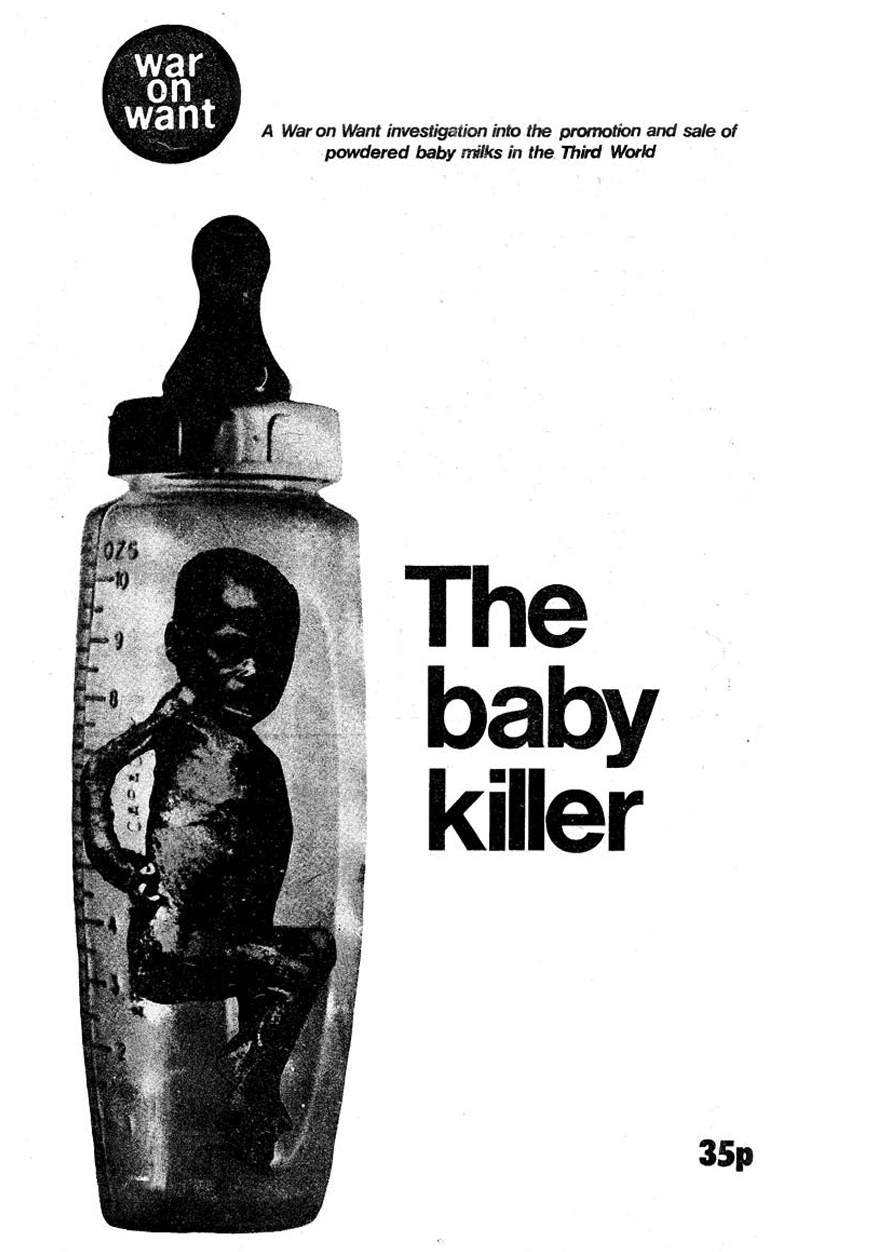

The world’s longest-running international advertising controversy involves the Nestle Corp. of Switzerland and its aggressive marketing of breast-milk substitutes. Advertising and marketing of powdered baby milk formula is not a problem in developed nations, such as the US, Europe and Japan. However, it can be dangerous and even lethal in under-developed nations where regular feeding with infant formula is too expensive, where clean water is not routinely available; and where a return to natural breast-feeding is impossible after a few days.

The controversy surfaced in a libel suit in 1973 over a publication entitled “The Baby Killer,” which alleged that Nestle’s marketing practices were deceptive and dangerous. An international boycott followed, and is still in effect as of 2022.

The World Health Organization has for many years recommended that infants be breast-fed for up to two years, and the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends up to one year. However, the US refused to join a UN resolution in 2018 that encouraged developing nations to adopt WHO guidelines.

MORE INFORMATION

International Baby Food Action Network

Norwegian video on Infant formula