In the United States of America, the legal guarantee of freedom of expression is found in the First Amendment to the Constitution.

It has six major clauses; two concerning religion, and one each in the areas of speech, press, assembly and petition:

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.

These six principles of freedom are as alive and important now as they were over 230 years ago. In the words of the MTSU Free Speech Center: “These liberties are neither liberal nor conservative, Democratic nor Republican — they are the basis for our representative democratic form of government.”

Although the First Amendment is subject to some interpretation, the basic principles and court decisions are “black letter law,” that is, they are so clear and so well supported by a string of important cases that they are beyond dispute. The most important First among these cases is New York Times v Sullivan, a 1964 case in which the Supreme Court said in its unanimous opinion:

We [have] … a profound national commitment to the principle that debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust, and wide-open, and that it may well include vehement, caustic, and sometimes unpleasantly sharp attacks on government and public officials.”. — New York Times v Sullivan

But if, as the First Amendment says, Congress shall make no law, how are differences to be resolved? How do we balance rights under the US Constitution?

The answer has been that the federal court system, and not Congress or the executive branch, and not the state courts, serves as the interpreter of constitutional law. This means that decisions of the court are the primary guides in the study of Constitutional law and the best way to predict what the law will be in any given situation.

For example, if someone accuses a journalist or news organization of libel, the first point of reference will be libel cases already decided by the US Supreme Court. So we look for the most significant libel case that is still “controlling” and sets out the guidelines of particular aspects of communications law. In libel, this would be the Sullivan case and the subsequent cases that refined the “Sullivan standard.” (We’ll learn more about this in the section on libel in this course).

Listen to the First Amendment song in More Perfect Union podcast from WNYC / NPR.

Human Rights worldwide

• Many other countries are also committed to free speech and press, and have their own foundational human rights documents and guarantees.

The most significant international document is the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights. Article 19:

Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.

And Article 18 says: Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion; this right includes freedom to change his religion or belief, and freedom, either alone or in community with others and in public or private, to manifest his religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship and observance.

The European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, Article 10, is also very significant:

Everyone has the right to freedom of expression. This right shall include freedom to hold opinions and to receive and impart information and ideas without interference by public authority and regardless of frontiers…

Disrespecting human rights

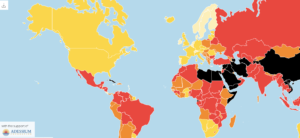

• Not every country respects human rights. While guarantees of free speech and press are intended to be global, as part of international law, they are not accepted in some countries. Two groups that measure respect for free speech and press are Reporters Without Borders and Freedom House. According to the RSF press freedom index, the US has only a “satisfactory” rating, while the World Press Freedom report by Freedom House, gives the US has a top rating.

MONEY CANT BUY EVERYTHING: In October, 2019, Houston Rockets manager Daryl Morey tweeted in support of Hong Kong freedom protesters. The tweet may have cost the NBA billions of dollars. But what about the greater cost if free speech is repressed in the US as it is in China? And why do American golfers and other athletes get a free pass when they travel to Saudi Arabia? The controversy illustrates the increasingly global nature of free speech issues.

This is in sharp contrast to the “very serious” situation in China, Saudi Arabia, and other countries, where the press is rated “not free” in the Reporters Without Borders world press freedom index.

In China, the basic idea of freedom of speech is endorsed in its Regulations on the Administration of Publishing (2001.12.25) (See US State Dept. site on Freedom of Expression in China). But observe the second clause– that’s the sticking point, and the truth is that even minor challenges to political authority in China can be met with harsh jail terms or execution. Article 5: All levels of the People’s Government shall ensure that citizens are able to legally exercise their right to freedom of publication. When citizens exercise their right to freedom of publication, they shall abide by the Constitution and laws; [they] shall not oppose the basic principles confirmed in the Constitution; and [they] shall not harm the interests of the country, the society or the collective or the legal freedoms and rights of other citizens. (This is why Chinese dissident Liu Xiaobo, who won the 2010 Nobel Peace Prize, spent so much jail time in China.)

In 2018 and 2019, China accelerated a crackdown on freedom of religion. According to The Guardian newspaper: China’s Communist party is intensifying religious persecution as Christianity’s popularity grows. A new state translation of the Bible will establish a ‘correct understanding’ of the text.

Chinese authorities have jailed more than 1,500 political prisoners since 2019 in Hong Kong. Newspaper publishers like Jimmy Lai are languishing in jail. The once-thriving democracy, and the promise of “one China, two systems,” was finally crushed in 2023.

Saudi Arabia is another example of an absolute dictatorship in constant violation of the UN Declaration of Human Rights. The international rights group Amnesty International reports that the Saudis periodically stage mass executions of dissidents following trials that are grossly unfair to defendants. Any criticism of the country, its policies, its rulers or its traditions can lead to torture or execution — a stand reaffirmed by a “Royal Decree“ April, 2011. Meanwhile, dissidents outside the country are routinely kidnapped and assassinated. (See BBC’s “Saudi Arabia’s Missing Princes.” (Aug. 17, 2017) and coverage of the assassination of Jamal Khashoggi in October 2018). In August, 2024, Saudi-US citizen Abdulaziz al-Muzaini, creator of the Masameer animated cartoon for Netflix, was sentenced to 13 years in prison on trumped- up charges.

Russia — Although the Russian constitution has an article expressly prohibiting censorship, in reality censorship is a constant factor in the life of the Russian media, according to the US-based Wilson Center. In addition to loss of employment and possible prison sentences, a long list of Russian journalists have been assassinated. One example: Russian dissident Alexei Navalny produced a set of videos attacking the “incessant marathon of disgraceful propaganda, lies, and censorship” that was found on Russian television. One of Navalny’s videos gave a tour of “Putin’s palace,” which he dubbed “the world’s largest bribe” (Ling, 2024). Navalny’s death in a Russian prison in February 2024 was followed with protests from human rights groups and Western governments.

Belarus — A satellite state of Russia, is notoriously repressive. A Washington Post article July 9, 2022, notes: “Danuta Perednya was an honors student at Mogilev State University in Belarus when Russia began a military onslaught against Ukraine. On Feb. 27, just days after the invasion, she reposted a text in an online chatroom that harshly criticized Presidents Alexander Lukashenko of Belarus and Vladimir Putin of Russia for unleashing the war… She was arrested and … sentenced to 6½ years in a penal colony — for simply expressing her views.” Belarus is “a dictatorship using terror and coercion against its own people to smother free speech and association” according to the Post.

READING

First Amendment Timeline from the Annenberg Center

First Amendment news from the Freedom Forum

Censorship in China – Council on Foreign Relations

How Saudi Arabia Gets Away With Murder – Council on Foreign Relations