The Enlightenment was a philosophical and cultural movement of the 17th and 18th centuries that tried, with some success, to reform the social order by challenging faith, tradition and superstition with rationality, human rights and a new relationship between the government and the governed. When we think of the “balance of powers” within a government, we can credit Enlightenment philosopher Montesquieu. When we think of the “social contract” we can thank John Locke. Milton’s concept of the “marketplace of ideas” emerged from this era. So, too, did other ideas, such as the notion of natural or God-given rights, or support for a generous view of political disagreements within the context of democracy.

Francis Bacon, English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and as Lord Chancellor of England. His works are credited with developing the scientific method and remained influential through the scientific revolution. Thomas Jefferson wrote: “Bacon, Locke and Newton. I consider them as the three greatest men that have ever lived, without any exception, and as having laid the foundation of those superstructures which have been raised in the Physical and Moral sciences.” Bacon was particularly interested in technological change and what it signified:

Printing, gunpowder and the compass: These three have changed the whole face and state of things throughout the world; the first in literature, the second in warfare, the third in navigation…” in Novum Organum 1620

John Milton (1608-1674) believed the truth would always win in a free and fair fight in the marketplace of ideas. Milton, also famous for Paradise Lost, wrote a 1644 plea to Parliament that he called the Areopagitica. Perhaps the most famous line is this:

John Milton (1608-1674) believed the truth would always win in a free and fair fight in the marketplace of ideas. Milton, also famous for Paradise Lost, wrote a 1644 plea to Parliament that he called the Areopagitica. Perhaps the most famous line is this:

“Though all the winds of doctrine were let loose to play upon the earth, so (long as) Truth be in the field, we do injuriously, by licencing and prohibiting to misdoubt her strength. Let her and Falsehood grapple; who ever knew Truth put to the worse, in a free and open encounter. (See Dartmouth text of Areopagitica).

(The name Areopagitica was a reference to the Athenian marketplace and also to a speech by Isocrates called the Areopagitic Discourse or Areopagiticus (about 355 BCE)

Francois Voltaire

Francois Voltaire (1694-1778) was perhaps the best known figure of the European Enlightenment. Francois-Marie Arouet, also known by his assumed name of Voltaire, was a prolific journalist, novelist and political thinker whose writing had a tremendous impact on the American revolution.

It was Voltaire who captured the spirit of the age by saying: “I may disagree with what you have to say, but I shall defend, to the death, your right to say it.” (Actually, this is a popular paraphrase of a sentiment that Voltaire often repeated but never said quite that succinctly.) Voltaire also helped Benjamin Franklin advance the cause of the American Revolution in Paris during the late 1770s. He believed, more than anything else, in toleration, the rule of law and freedom of opinion.

Summing up the English Civil War by comparing Rome and England, Voltaire said: “The Romans never knew the dreadful folly of religious wars, an abomination reserved for devout preachers of patience and humility. Marious and Sylla, Caesar and Pompey, Anthony and Augustus, did not draw their swords and set the world in a blaze merely to determine whether the flamen (priest) should wear his shirt over his robe, or his robe over his shirt… But here follows a more essential difference between Rome and England, which gives the advantage entirely to the later – viz., that the civil wars of Rome ended in slavery, and those of the English in liberty. The English are the only people upon earth who have been able to prescribe limits to the power of kings by resisting them; and who, by a series of struggles, have at last established that wise Government where the Prince is all powerful to do good, and, at the same time, is restrained from committing evil… “ (See Letters on the English, 1778, esp. Section VIII, On the Parliament.)

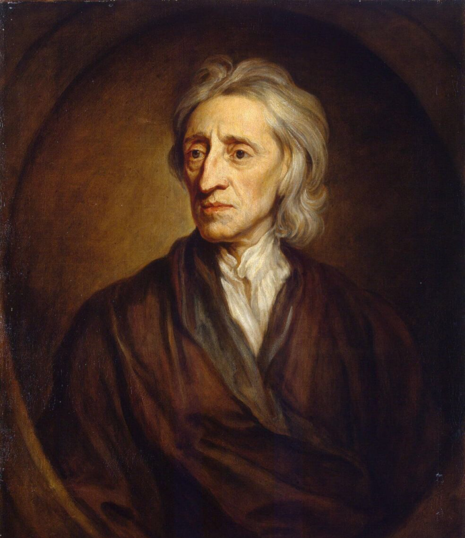

John Locke

John Locke (1632-1704) was an English philosopher, naturalist and physician who helped start the Enlightenment in England and France. Often called the architect of democracy, Locke’s concept of the social contract was the foundation for the U.S. Constitution, as well the framework of government in many other nations. He was the author of, among other works, A Letter Concerning Toleration (1689) and An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1694) The book opposed press licensing and advanced two important ideas:

1) People and government had a social contract and government existed to serve the people, not the other way around;

2) People had natural rights to life, liberty and property.

Locke is often both applauded and denounced for his contribution to the 1669 Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina, which advanced religious tolerance but created the harsh legal framework for “absolute power and authority over … negro slaves.”

David Hume (1711-76), a Scottish journalist and philosopher, was a pioneer of social psychology and a champion of free press. He rejected absolutes (and inspired the opposing view in Immanuel Kant). His philosophy echoed Greek stoics and Romans like Cicero.

He wrote Essays, Moral and Political in two volumes in 1741 and 1742 and a history of England. Hume saw freedom of the press as offering no threat to rulers, however much it might be abused. Press freedom can not excite popular tumults or rebellions because “a man reads a book or pamphlet alone coolly. There is no one present from whom he can catch the passion by contagion.”

Montesquieu

Baron de Montesquieu (1689-1755), a French philosopher, created the idea of the separation of powers, arguing in his 1748 book On the Spirit of the Laws that the best government would be one in which power was balanced among three groups of officials. He thought England – which divided power between the king (who enforced laws), Parliament (which made laws), and the judges of the English courts (who interpreted laws) – was a good model.

Montesquieu also believed that if the powers of government were limited, people would be free to follow their natural inclinations and do the right thing.

Olympe de Gouges (1748 – 1793) was the French author of the Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen, an essay written in response to the 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen which did not extend equal rights to women after the French revolution. A passionate advocate of human rights, she was one of France’s earliest public opponents of slavery. Her plays and pamphlets spanned issues ranging from divorce and marriage, children’s rights, unemployment and social security. She was executed for her outspoken advocacy at the height of the Reign of Terror.

De Gouges opens her Declaration with the famous quote, “Man, are you capable of being fair? A woman is asking: at least you will allow her that right. Tell me? What gave you the sovereign right to oppress my sex?”

John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill (1773-1836) was an English utilitarian philosopher and historian who expanded on Milton’s Marketplace of ideas by arguing that:

1) A censored opinion may be true and the accepted view may be in error

2) Even error may contain particle of truth

3) Truth may be held as prejudice, not rationally

4) Even completely false ideas should not be suppressed, since truth loses vitality if not contested from time to time.

“The peculiar evil of silencing the expression of an opinion is, that it is robbing the human race; posterity as well as the existing generation; those who dissent from the opinion, still more than those who hold it. If the opinion is right, they are deprived of the opportunity of exchanging error for truth: if wrong, they lose, what is almost as great a benefit, the clearer perception and livelier impression of truth, produced by its collision with error.”

As a utilitarian, Mill emphasized the greatest good for the greatest number of people. However, he also warned against majority tyranny: “Protection against the tyranny of the magistrate is not enough: there needs to be protection also against the tyranny of the prevailing opinion and feeling; against the tendency of society to impose … its own ideas and practices as rules of conduct on those who dissent from them; to fetter the development and, if possible, prevent the formation of any individuality not in harmony with its ways and compel all characters to fashion themselves upon the model of its own.”

Mill’s “harm” principle is at the heart of most media law in the Western world: “The only purpose for which power can be rightly exercised over any member of a civilized community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others.”

Thomas Jefferson (1743 – 1826), the principal author of the Declaration of Independence (1776) and the third President of the United States (1801–1809) is also considered an Enlightenment figure.

Thomas Jefferson (1743 – 1826), the principal author of the Declaration of Independence (1776) and the third President of the United States (1801–1809) is also considered an Enlightenment figure.

The idea behind the First Amendment, Jefferson said, was this: “No experiment can be more interesting than that we are now trying, and which we trust will end in establishing the fact, that man may be governed by reason and truth. Our first object should therefore be, to leave open to him all the avenues to truth. The most effectual hitherto found, is the freedom of the press.”

Jefferson’s arguments for religious tolerance are compelling:

“Millions of innocent men, women and children, since the introduction of Christianity, have been burnt, tortured, fined, imprisoned; yet we have not advanced one inch towards uniformity. What has been the effect of coercion? To make half the world fools, and the other half hypocrites.”

“What, but education, has advanced us beyond the condition of our indigenous neighbors? And what chains them to their present state of barbarism and wretchedness,* but a bigoted veneration for the supposed superlative wisdom of their fathers, and the preposterous idea that they are to look backward for better things, and not forward, longing, as it should seem, to return to the days of eating acorns and roots, rather than indulge in the degeneracies of civilization?

“And how much more encouraging to the achievements of science and improvement is this, than the desponding view that the condition of man cannot be ameliorated, that what has been must ever be, and that to secure ourselves where we are, we must tread with awful reverence in the footsteps of our fathers. This doctrine is the genuine fruit of the alliance between Church and State; the tenants of which, finding themselves but too well in their present condition, oppose all advances which might unmask their usurpations, and monopolies of honors, wealth, and power, and fear every change, as endangering the comforts they now hold”. — Thomas Jefferson, Report of the Commissioners for the University of Virginia.

Thomas Jefferson, slavery and Indian removal.

We need to distinguish the ideals of the American Revolution and the US Constitution from the actual treatment of African Americans and Indians.

The way Jefferson viewed Native Americans (“savages,” above) is demeaning and objectionable from the modern viewpoint. While the clear targets of Jefferson’s disdain here are the advocates of Church-State alliances, Jefferson’s ideas about Native Americans were sadly typical of the time and of the European mind-set.

Jefferson defended American Indians in his Notes on the State of Virginia, According to the Monticello foundation. For example, Jefferson held up a speech by Mingo chief Logan, who mourned the loss of his family in an attack by a white settler. “Logan’s Lament” was great and powerful oratory, the equal of any European orator, classical or modern, Jefferson said.

Jefferson also wrote in a letter to the Marquis de Chastellux.: “I believe the Indian … to be in body and mind equal to the white man.” On the other hand, Jefferson also advocated Indian removal, by force if necessary, to regions west of the Mississippi.

And of course, Jefferson owned 600 slaves in his lifetime and sometimes acknowledged the hypocrisy of advocating freedom for White people and not for Blacks.