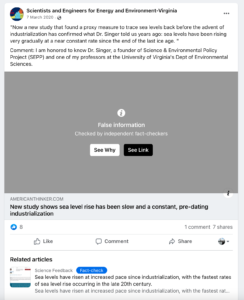

June 18, 2016, FB post with falsehoods about proposed law, and related falsehoods about climate science. Question: Who decides what is a lie?

What happens when a law designed to prevent false and misleading commercial advertising is applied to larger issues such as climate change? Take, for instance, a proposed California law, SB 1161 of 2016, designed to bring corporations into court to defend climate change denial. No individual lawsuits, and no criminal penalties, had ever been part of the failed legislative proposal.

But even after the proposal failed to clear a state house committee, opponents associated with the fossil fuel industry published pictures of Nazi soldiers, claimed the law would have jailed dissidents, and proclaimed the death of the First Amendment.

Of course, these are not mere “opinions” under the Ollman test. They are testable facts and, following a reasonable test, outright fabrications. And the fact that corporations openly publish lies about public affairs in order to advance their agenda is nothing new. The power of social media advertising to allow corporations to target susceptible individuals is the new element.

Dangerous commercial and corporate speech has existed since the early days of advertising, when there was no regulation. At the time, cereals and opioids were hawked as curing appendicitis and cancer. That kind of false advertising is illegal today because of the damage caused by unethical advertising practices.

Today, the question about false and

A climate denial group’s post claiming that scientists are wrong about sea level rise is challenged by fact checkers. Usually such claims are ignored.

misleading advertising overlaps with questions about the First Amendment rights of corporations and public relations practitioners working with the corporations.

While information about products must be truthful, is there, in effect, a right to lie about broader issues like climate change or vaccine efficacy or rigged voting machines?

Consider this: Even if the First Amendment only protects truthful communication, how difficult is it for courts to decide between truth and error? And even if some communication is in error, isn’t John Stuart Mill’s idea about allowing error in order to provide a livelier impression of truth at the very heart of the common law approach to freedom of speech? What about Justice Louis Brandeis’ idea (from Whitney v. Calif.) that “the fitting remedy for evil counsels is good ones?” In other words, trust the marketplace of ideas.

Among the major issues that have surfaced around corporate speech in recent decades are:

- Regulation of corporate / commercial advertising, including truth-in-advertising laws relative to corporate public relations; and

- The First Amendment implications of US campaign finance laws and the financial power of corporations to dominate the national discussion.

Regulation of corporate / commercial advertising

Consolidated Edison Co. v. PSC 1980 — Con-Ed inserted a promotion for nuclear power technology in its regular monthly bills. The Natural Resources Defense Council, a group opposed to nuclear power, wanted to insert their own arguments into consumers bills. Since there was no guarantee of access under Miami Herald v. Tornillo or Red Lion v. FCC (which applies only to scarce airwaves), the PSC told Con Ed to stop advertising controversial stuff.

The NY supreme court said that was reasonable time, place and manner restriction on free speech. US Supreme Court reversed, said the ban wasn’t reasonable time place restriction or a narrowly tailored way to serve a compelling state interest. Prior restraint on commercial speech has to be content neutral. The case took place around the same times as the Central Hudson case (above), which resulted in a four-part test for restrictions on advertising and corporate speech.

** Nike v. Kasky, 2003 — In April 1998, California activist Marc Kasky sued Nike for unfair and deceptive practices under California’s Unfair Competition Law and False Advertising Law. He asserted that “in order to maintain and/or increase its sales,” Nike made a number of “false statements and/or material omissions of fact” concerning the working conditions under which Nike products are manufactured in foreign facilities.

The US Supreme Court decided not to hear the case for procedural reasons. Nevertheless, the court noted that new First Amendment questions were presented. “On the one hand, if the allegations of the complaint are true, direct communications with customers and potential customers that were intended to generate sales–and possibly to maintain or enhance the market value of Nike’s stock–contained significant factual misstatements. The regulatory interest in protecting market participants from being misled by such misstatements is of the highest order. That is why we have broadly (perhaps overbroadly) stated that “there is no constitutional value in false statements of fact”– eg Gertz v. Robert Welch, Inc., 418 U. S. 323(1974). On the other hand, the communications were part of an ongoing discussion and debate about important public issues that was concerned not only with Nike’s labor practices, but with similar practices used by other multinational corporations… Knowledgeable persons should be free to participate in such debate without fear of unfair reprisal. The interest in protecting such participants from the chilling effect of the prospect of expensive litigation is therefore also a matter of great importance… That is why we have provided such broad protection for misstatements about public figures that are not animated by malice. See New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U. S. 254 (1964). See the First Amendment Center’s article on this case.

Constitutional issues regarding campaign finance laws and advertising

Restrictions on campaign financing directly affect advertising since anywhere from 70 to 90 percent of a political campaign’s expenditures involve some form of advertising. Because of the influence of corporations and unions on elections through campaign fund raising, Congress has wrestled with restrictions on campaign financing for decades. One of the first reform laws passed in this area was the Federal Election Campaign Act of 1974 which set limits on campaign contributions and mandated disclosure of campaign contributions.

Buckley v. Valeo, 1976 — Tested the Federal Election Campaign Act of 1974 , and the US Supreme Court upheld the law in 1976. But the court also ruled that spending money to influence elections is a form of constitutionally protected free speech, and struck down portions of the law. The court also stated candidates can personally give unlimited amounts of money to their own campaigns.

* First National Bank of Boston v. Bellotti, 1978 — A state statute prohibited commercial businesses from getting involved in public affairs unless they were directly affected. 1st National campaigned against a progressive personal income tax. Court held that non-media corporations have at least some first amendment rights. This case is very interesting because of the influence of corporations on later public initiatives, such as Proposition 87 in California in 2006. In Bellotti,

Chief Justice Rehnquist’s dissent has been of particular interest among those who believe corporate speech should be regulated. Rehnquist said:

“A state grants to a business corporation the blessings of potentially perpetual life and limited liability to enhance its efficiency as an economic entity. It might reasonably be concluded that those properties, so beneficial in the economic sphere, pose special dangers in the political sphere… Furthermore, it might be argued that liberties of political expression are not at all necessary to effectuate the purposes for which States permit commercial corporations to exist. So long as the Judicial Branches of the State and Federal Governments remain open to protect the corporation’s interest in its property, it has no need, though it may have the desire, to petition the political branches for similar protection. Indeed, the States might reasonably fear that the corporation would use its economic power to obtain further benefits beyond those already bestowed. 6 I would think that any particular form of organization upon which the State confers special privileges or immunities different from those of natural persons would be subject to like regulation, whether the organization is a labor union, a partnership, a trade association, or a corporation. ..”

McConnell v. Federal Election Commission, 540 U.S. 93 (2003 — Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of most of the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002, also known as the McCain Fiengold Act. The question was whether the Federal Elections Commission can regulate speech by regulating campaign spending on political advertising , which has an enormous influence over the outcome of political campaigns. According to a Wikipedia article:

“The BCRA was a mixed bag for those who wanted to remove the money from politics. It eliminated all soft money donations to the national party committees–but it also doubled the contribution limit of hard money, from $1,000 to $2,000 per election cycle, with a built-in increase for inflation. In addition, the bill aimed to curtail so called “issue ads” by banning the use of corporate or union money to pay for broadcast advertising that identifies a federal candidate within 30 days of a primary or nominating convention, or 60 days of a general election. Any ads within those periods that identify a federal candidate must be paid for with regulated, hard money or with contributions exclusively made by individual donors.”

* Citizens United v Federal Election Commission, 558 U.S. 50 (2010), — a landmark and hotly controversial Supreme Court decision holding that corporate financing of political advertising is free speech under the First Amendment. Attempts to limit corporate influence in politics had included the McCain Fiengold Act. According to the Wikipedia article: The 5–4 decision resulted from a dispute over whether the non-profit corporation Citizens United could air via video on demand a critical film about Hillary Clinton, and whether the group could advertise the film in broadcast ads featuring Clinton’s image, in apparent violation of the … McCain–Feingold Act.

The Citizens United decision continues to be controversial years later, especially since the lack of disclosure allowed Russian interference in the 2016 US presidential election.

More

“Foreign money in US elections,: The Intercept, August 3, 2016

A Bill Moyers critique of the impact of Citizens United is found here.

Facebook’s policies on challenging climate denial are discussed here.

Federal Trade Commission guidance on public relations online , Institute for Public Relations, Feb. 2014.