William Tell is arrested for refusing to salute a Swiss ruler’s hat. (Swiss National Museum, Hans Sandreuter, 1901).

Compelled (or forced) speech is an ancient form of tyranny.

One of the most famous examples of opposition to compelled political speech comes from the legend of William Tell, a Swiss archer who, in the year 1307, refused to salute the hat of Albrecht Gessler, a tyrannical ruler. To punish him, Gessler forced Tell to shoot an apple from his son’s head using his crossbow. Naturally, if he missed, Tell could have killed his own son. Tell showed up with two arrows. The second one. was for Gessler.

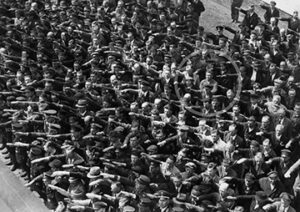

Another interesting example of resistance to compelled speech involves August Landmasser, a German shipyard worker who refused to take part in the Nazi salute. The photo is from the launching of the training ship ‘Horst Wessel’ on June 13, 1936 in Hamburg, Germany.

Opposition to compelled religious speech was a part of the original Enlightenment philosophy of government, as noted in the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom of 1779.

And, as Thomas Jefferson said in his 1785 book Notes on the state of Virginia:

Millions of innocent men, women, and children, since the introduction of Christianity, have been burnt, tortured, fined, imprisoned; yet we have not advance one inch towards uniformity. What has been the effect of coercion? To make one half the world fools, and the other half hypocrites. To support roguery and error all over the earth.

Questions about compelled religious speech also involve taxation, and they are still argued today, for instance, in the controversy over taxpayer support for religious universities.

Compelled speech in US law

In the US, compelled speech and related “free exercise of religion” issues have come up many times. One important group of cases have been involved Jehovah’s Witnesses, a religious denomination whose leader saw patriotic symbols as “idolatry.”

In 1940, a school district in Pennsylvania insisted that students begin their day by reciting the Pledge of Allegiance and saluting the US flag. In this case, Minersville School District v. Gobitis, the Supreme Court upheld the compulsory salute, despite parents’ religious objections, saying that the First Amendment never included any ““exemption from doing what society thinks necessary for the promotion of some great common end.”

Writing for the majority, Justice Felix Frankfurter said Frankfurter said the question in Gobitis was how to decide the means to reach that great common end, “without which there can ultimately be no liberties, civil or religious.” Should the Supreme Court decide, and thereby become “the school board country?” Or should the decision be left to the individual state legislatures and school districts? Frankfurter said the court should choose the local option, even though some local decisions may turn out to be harsh or foolish.

Bellamy salute 1941 was similar to the Nazi “sieg heil” and was a factor in overturning Gobitis. (Wikipedia)

In a dissenting opinion, Justice Harlan Fiske Stone said that the Constitution did not indicate how “compulsory expressions of loyalty play any . . . part in our scheme of government.” Compelling the Gobitas children to publicly violate their “religious conscience” should be declared unconstitutional.

One popular objection to the Gobitis decision was that in many cases it compelled a “Bellamy salute,” which was an arm-extended, palm down salute similar to the one used by the Nazi party in Germany.

But other issues were also on the table, for example, how to punish the children who refused to salute. Should they be taken away from their parents and sent to a reformatory for their criminal behavior?

When the state of West Virginia appeared to be specifically targeting Jehovah’s Witnesses, a new federal case was filed along the same lines as Gobitis. In West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette (1943), the court reversed Gobits and said that schools could NOT force students to salute the flag. The court’s 6–3 decision, is remembered for its eloquent defense of free speech and constitutional rights. The opinion, written by Justice Robert H. Jackson, said:

If there is any fixed star in our constitutional constellation, it is that no official, high or petty, can prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion, or force citizens to confess by word or act their faith therein.

Associated Press and the “Gulf of America”

On Jan. 20, 2025, the new administration of Donald Trump signed Executive Order 14172 directing federal agencies to adopt the name “Gulf of America” for the body of water that had been called the Gulf of Mexico for at least 300 years. Google Maps, Apple Maps, Bing Maps, and several U.S.-based media outlets such as USA Today, Axios, and Fox News have also adopted the change. One organization that did not adopt the change was the Associated Press, which said that since it serves and international audience, it would not be. appropriate to reflect a US-only name change.

In order to coerce the Associated Press to use the “Gulf of America” name, the Trump administration ordered that AP reporters and photographers be banned from all government news conferences and events. The AP sued in federal court but was unable to secure an immediate injunction against the discriminatory and coercive policy.

Similar FORCED Speech cases

In Miami Herald v. Tornillo, 1974, a state law forcing a newspaper to run a political candidate’s advertisement was ruled unconstitutional. However, compelled speech in radio and TV programming is permissible, for example in the Turner Broadcasting v FCC case (1994), in which the courts said that local stations had to be carried by cable companies. This is because broadcasting is directly regulated by the FCC, unlike print or web or most other media in the US. (This comes up again in our study of advertising law).

Loyalty to Israel? In Texas? Most recently, the arguments against compelled speech were used to fight a requirement to sign an oath pledging not to boycott the nation of Israel that is (or was) a precondition for employment in the Austin, Texas school system. Some have seen this as a “loyalty oath” and have been fired, while others claim it is a commercial (not a speech) case.

Strict scrutiny: In all of these cases, the Constitutional question is framed through a strict scrutiny standard: a compelling state interest being achieved with the least restrictive means necessary.

Among other compelled speech cases are:

Sweezy v. New Hampshire (1957) — Due process and compelled speech questions rise from a state investigation of a university speaker.

Keyishian v. Board of Regents, 385 U.S. 589 (1967) — Court held that states cannot prohibit employees from being members of the Communist Party and that such laws are overly broad and too vague.

Wisconsin v. Yoder (1972) – Court ruled that Amish children were not required by states law to attend school past the 8th grade because their religious freedom guaranteed in the First Amendment superseded that.

Wooley v. Maynard (1977) — People who didn’t like the “Live Free or Die” license plate for New Hampshire didnt have to display it, the court said. (Minersvill, Barnette, this Wooley case and several other cases are sometimes called the Jehovah’s Witnesses cases because they were brought by people of that denomination).

Turner Broadcasting v FCC (1994). The Turner cable company and others objected to FCC “must carry” rules that forced them to include local broadcasting stations in their cable bundle. The courts ruled that under previous decisions (like Red Lion v FCC 1969) a strict scrutiny standard is not applied to federal regulation of broadcasting, and less restrictive standards giving the government more regulatory power can be used. (This comes up again in our study of broadcasting law).

Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System v. Southworth (2000) –Court held that public universities may subsidize campus groups by means of a mandatory student activity fee without violating the students’ First Amendment rights.

Government speech

A related area is speech by government, which is theoretically speech by all citizens, and thus can be seen as compelled speech. To what extent does government speech have to be content neutral and permissive of all expression?

Not always and not so much, the courts have said. For instance, in Walker v Texas Division, Sons of Confederate Veterans, (2015), in which the court said that the state of Texas could refuse to allow Confederate groups to display the confederate flag on a license plate.

Also in Pleasant Grove City v Summum (2009), the court said that a city could accept a donation of a religious statue from one private group (with the 10 Commandments) but not another (a fringe religious movement). Here the court said that the city itself had a right of free speech. “Government speech” is a conservative rationale here for allowing religious icons on pubic property. Usually government expression, as such, is protected only insofar as it directly relates to a public function of government.

However, the Ten Commandments cases of the late 20th and early 21st century have presented problems involving the Establishment Clause of the US Constitution, and the general question of the separation of church and state.

What’s wrong with displaying the Ten Commandments? Conservatives would like to see historical reminders of religious obligations as underpinnings of social morality, and indeed, no one argues against prohibitions of murder, theft or perjury (Commandments 6, 8, and 9).

Liberals note that inconsistencies in the Ten Commandments make it an unsuitable basis for law in a society where equal justice is the foundation. For instance, should the government endorse the idea of honoring one’s parents (5th), or prohibiting adultery (7th) or even swearing (3rd)? Is it wrong for Hindus to worship what Christians would see as idols or “graven images?” Even the three major faiths that rely on the Ten Commandments — Islam, Judaism and Christianity — do not agree on which day of the week to honor (4th) the Sabbath.

Therefore, to give preference to only one religious code, when many others are also part of the social fabric, presents Constitutional problems.

Murthy v. Missouri (2024)was an important case that answered the question: Can the federal government attempt to influence private social media companies’ content-moderation decisions? Is that a state action that violates First Amendment rights? The state of Missouri claimed that US Surgeon General Murthy’s attempts to influence social media about “anti-vax” rhetoric was a violation. The Supreme Court disagreed.

Patents and trademarks as government speech

Government speech was also an issue in the Redskins football team cases. Under the Lanham Act, trademark registrations could not be “disparaging, scandalous, contemptuous, or disreputable.” The team name “Redskins” was disparaging, courts said. But in a 2017 case Matal v Tam, the US Supreme Court overturned the section of the Lanham Act that prohibited disparagement and reversed the underlying legal assuming that any trademark approval was in effect governmental speech. In 2019, a similar case, Iancu v Brunetti, allowed trademark registration of a clothing line called “Fuct.”

For more detail see this site under Patent and Trademark issues.

More Reading

Alex Aichinger, “Minersville School District v. Gobitis (1940),” MTSU First Amendment Encyclopedia, 2009.