Also known as “prior restraint,” censorship is when government (local, state or federal) prevents the publication or distribution of books, films, newspapers or other media over objections about content. Censorship by government raises Constitutional issues, and may trigger “strict scrutiny” review in the courts.

An important point here is that the US First Amendment prohibits government censorship. This is called the “state action doctrine.” When censorship occurs between private people or entities, the courts may be asked to protect private First Amendment rights. Usually, the courts side with the private entities and their right to make editorial decisions.

When the New York Times does or does not print a letter to the editor, it is their call under the First Amendment. A decision by YouTube to promote (or demote) videos by the Prager group (*not an actual university) was not an infringement of Prager’s First Amendment rights, but rather, an exercise of YouTube’s editorial rights under the First Amendment. (See articles in Harvard Law Review and Columbia University’s Global Freedom of Expression about Prager v YouTube, 2020).

Globally, intervention by governments in the content of social media is an ongoing battle between a wide variety of forces involving questions of social responsibility and freedom of expression on all sides of the political spectrum. Some of these battles are described in series of editorials in the Washington Post and the London-based Financial Times. (Most of our emphasis in this course is on US law, but we need to keep an eye on international media issues as well).

Censorship dates back thousands of years.

Ancient philosophers such as Confucius and Socrates, and many more, faced censorship, banishment, or execution when governments considered their ideas dangerous. The term “censor” comes from the Latin word cēnseō which means “to give an opinion, judge; to assess, reckon; to decree, determine.” In ancient Rome, censors were magistrates whose duties included supervising the census and guarding moral conduct and speech.

“Just as in ancient Grecian communities, the Roman ideal of good governance included shaping the character of the people. Censorship was thus regarded as an honorable task,” said Leyton Grey in a History of Censorship for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy of Winnipeg. “Censorship has followed the free expression of men and women like a shadow throughout history.”

US historian Mary E. Hull notes that the writings of ancient Chinese philosopher Confucius were censored when an emperor considered his ideas dangerous. China’s first censorship law was made over 1,700 years ago, and it is still a basic feature of Chinese society today.

The expansion of mass media with the printing press in the 1450s led to increased demands for church and government censorship in Europe. The Catholic Church issued and updated an “Index of Prohibited Books” from 1560 to 1948, and took an active role in banning lewd or irreverent movies until the 1950s. And in fifteenth century England, licensing acts were designed to silence unorthodox writers and thinkers.

William Blackstone, British jurist, opposed prior restraint censorship

Routine prior restraint of printing ended around 1689 in Britain with the Glorious Revolution of the adoption of the English Bill of Rights. And as we have seen (in Section 3), discussions about political freedom and freedom of the press begin emerging in this era. Milton’s Areopagitica, Montesque’s Spirit of the Laws, the Cato Letters, are known alongside arguments for free speech by American revolutionaries like Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Paine, Sam Adams and Patrick Henry.

In the 1700s. William Blackstone, a prominent British legal scholar, wrote in his Commentaries on the Laws of England (published in four volumes from 1765 to 1769):

“The liberty of the press is indeed essential to the nature of a free state: but this consists in laying no prior restraints upon publications, and not in freedom from censure for criminal matter when published.”

The US has wrestled with censorship throughout its history. An early example of the ongoing fight against censorship was the trial of New York publisher John Peter Zenger in 1734. He was accused of seditious libel — saying defamatory things about the government — but the jury found that Zenger printed the truth about the government, and this established the precedent that truth should be accepted as a defense in libel.

We’ve covered some of the background about the US Constitution of 1787 and the formation of the First Amendment in 1791, and the contradiction to law in the Alien & Sedition Acts of 1798 (which expired in 1800). We’ve also noted that before the Civil War, state laws imposed heavy censorship, with strong penalties for discussions or publications advocating the abolition of slavery. After the Civil War, and well into the 20th century, critics of Jim Crow racism were often punished by states or through extra-legal riots and lynchings.

Censorship has been officially imposed during times of national emergency. During World War I, thousands of people were jailed under the Sedition Act of 1918. which turned critics of the government into criminals, whether or not they advocated non-violent change.

We’ll look at three major prior restraint cases involving direct government censorship of individuals:

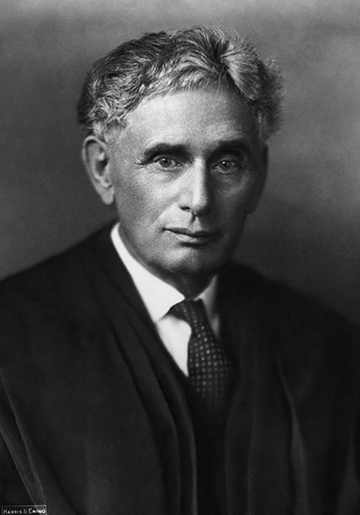

Louis Brandeis: “Those who won our independence by revolution were not cowards. They did not fear political change. They did not exalt order at the cost of liberty….”

- In Charles T. Schenck v. U.S., 1919, the court tested the conviction of a Philadelphia socialist who passed out leaflets against the draft. The ourt came up with the “Clear and Present Danger” standard.

- In Charlotte Whitney v. California, 1927, the California anti-communist (syndicalism) act was upheld, and a prominent socialite who backed the IWW was ordered to jail. The case is noted for an eloquent dissent by Justice Louis Brandeis.

- In Brandenburg v. Ohio, 1969, Ku Klux Klan member Clarence Brandenburg was convicted of advocating violence under a “criminal syndicalism” law. On appeal, the US Supreme Court found the Ohio law unconstitutional, and changed the standard from “clear and present danger” to “Imminent action.”

And also three press freedom cases involving government censorship of the media:

- Near v. Minnesota, 1933 — In which the State of Minnesota was prevented from banning a publication outright. Public officials, however, are free to sue for libel and other damage to reputation.

- Trinity Methodist Church v Federal Radio Commission, 1932 — In which the FRC refused to renew the broadcasting license of KGEF in Los Angeles on the basis that the station did not serve “the public interest, convenience, and necessity.” The US Supreme Court upheld the FRC on appeal. This shows the difference between the application of media law for broadcast media as opposed to printed media.

- US vs New York Times, 1971 — In which the Nixon administration failed to obtain a US Supreme Court injunction to prevent publication of the secret history of the Vietnam War often called “The Pentagon Papers.”

We’ll also consider a dozen other cases

… in areas concerning symbolic speech, compelled speech, hate speech, and suppression of obscene materials.

Reading

“The First Amendment Doesnt protect Trump’s Incitement,” Washington Post, Perspective by Einer Elhauge. P

Mary E. Hull, Censorship in America : A Reference Handbook (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC Clio, 1999).

Leyton Grey, A Short History of Censorship Frontier Centre for Public Policy (Winnipeg, Canada). 2021

Elizabeth. R. Purdy, Censorship, First Amendment Encyclopedia, MTSU, 2009.

US National Archives, Record of Rights, web publication.

Charles Schenck’s “silly leaflet.” US National Archives.