The internet and web emerged from the work of an improbable group of hackers who were guided by a vision of free global communication. For example, much of the crucial software (such as the Apache web server) was created and distributed for free.

The same spirit of freedom is reflected in the preamble of Section 230 of the Telecommunications law (US Code Title 47) which says the internet is “an extraordinary advance in the availability of educational and informational resources to our citizens.”

To understand why Section 230 is so significant today, sometimes called the “Magna Carta of the Internet,” it helps to understand the origins of the law.

Internet Libel

In the early 1990s, the internet was accessed through “Internet Service Providers” (ISPs). These were phone companies or similar firms operating as common carriers. Clearly, they were no more responsible for the content of the Internet than the phone company would be for the content of a regular voice phone call.

The unusual characteristics of the new digital media soon became clear with two libel cases from the early 1990s: Cubby v Compuserv (1991) and Stratton Oakmont v Prodigy (1995) If an ISP or a content provider took any steps to edit or block some content, they were considered to be responsible for ALL of that content. If the ISP took a “hands off” approach, and did no editing whatsoever, they were NOT considered responsible for any content.

And so, to be safe, the ISPs did nothing at all.

This was not a popular stance in 1995, when the internet was a relatively lawless frontier. One of the most alarming things was that pornographic videos were easily available to children, and a kind of moral panic took place, as seen in this July 3, 1995 Time Magazine cover.

This was not a popular stance in 1995, when the internet was a relatively lawless frontier. One of the most alarming things was that pornographic videos were easily available to children, and a kind of moral panic took place, as seen in this July 3, 1995 Time Magazine cover.

Congress reacted by passing the 1996 “Communications Decency Act” to regulate pornographic and indecent material on the internet. It became law but was immediately challenged as overly broad by the ACLU, and the law was defended by then-Attorney General Janet Reno. In Reno v ACLU, the US Supreme Court upheld part of the law and struck down other parts. The part that survived was called the “good samaritan” provision because it protected private blocking and screening of offensive material.

So now, after Reno v ACLU, if obscene or libelous or illegal materials were placed on a site by someone who didn’t work for the site (a third party), that company could remove those materials without risk of being sued. In other words, the law was meant to protect the social media company from lawsuits over third-party content. That’s why it was a “good samaritan” law, because it protected people who were trying to do the right thing. It was the third party, the one placing the materials online, who was supposed to bear the blame, take down offensive or libelous or illegal materials, and pay the damages.

Internet libel test case:

In a major test case, Zeran v AOL, 1997, internet company AOL was held NOT to be responsible for harms caused by false and malicious attacks on Zeran through AOL even though it did very little to take down the attacks. In effect, the Zeran case upheld Section 230, but in a way that was unexpected: Zeran let AOL do nothing.

This “either – or” dilemma over content moderation would not have occurred in traditional media, where publishers and broadcasters are responsible for all content, no matter how it is distributed.

However, as the Internet became increasingly populated with user-generated content, the issue of moderation became a major problem, since some relatively simple non-protected content (for example libel, private facts, pornography, incitement to violence) did not have to be edited. Many companies believed that trying to police the enormous flood of content coming through the Internet and the World Wide Web would hold back the development of promising new digital media.

(1) Treatment of publisher or speaker — No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider.

(2) Civil liability — No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be held liable on account of-

(A) any action voluntarily taken in good faith to restrict access to or availability of material that the provider or user considers to be obscene, lewd, lascivious, filthy, excessively violent, harassing, or otherwise objectionable, whether or not such material is constitutionally protected; or

(B) any action taken to enable or make available to information content providers or others the technical means to restrict access to material described in paragraph 1.

Effect of Section 230

- Section 230 insulates ISPs and Social media like Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, TwitchTV, etc. from responsibility for violations of law by its users. The author of a Facebook post or the producer of a YouTube video is still responsible for violations of the law.

- The problem is that even when a video or a post is a clear violation of the ISPs ethical terms of service, it is under no obligation to take down objectionable material. In some cases, the material has not been taken down due to policies that favor profits over ethics.

- Critics argue that Section 230 has gone too far, and that social media should at least be required to take down content that is violent, defamatory or invasive.

The controversy

Now that the companies originally protected by Section 230 are media giants, they are far more capable of taking responsibility for what it published on their sites by third parties.

Adding fuel to the fire, allegations by Facebook whistleblower Frances Haugen (in October, 2021 testimony before US Senate and UK Parliamentary committees) that the social network’s algorithms promote angry content to keep people engaged on the platform. They chose money over safety, she alleged.

There are three basic positions on Section 230 regulation: Too much (conservative), not enough (liberal) and don’t even touch it (libertarian).

On the “too much” side, many in the Trump wing of the Republican party believe that the big social media companies have no business correcting them, even if what they say may be false or defamatory. Donald Trump hated the law and has tried repeatedly to get rid of it when he was president. He even vetoed a Defense appropriations bill when it did not conform to his demands over Section 230, but his veto was over – ridden by both House and Senate in December 2020.

Ultra-conservative Justice Clarence Thomas has proposed using “common carrier” and “public accommodation” analogies to structure even further deregulation of the internet and web, but these analogies have been faulted as inappropriate given the neutrality expected of a public carrier, which cannot be neutral if social media companies use algorithms to individualize content.

On the libertarian side, free speech advocates like the Electronic Frontier Foundation are adamant about the value of Section 230, while also saying that the tech giants don’t do enough to combat hate speech and disinformation online.

Democrats and some center-right Republicans are angling for reform, and in September, 2022, President Joe Biden announced support for reform efforts.

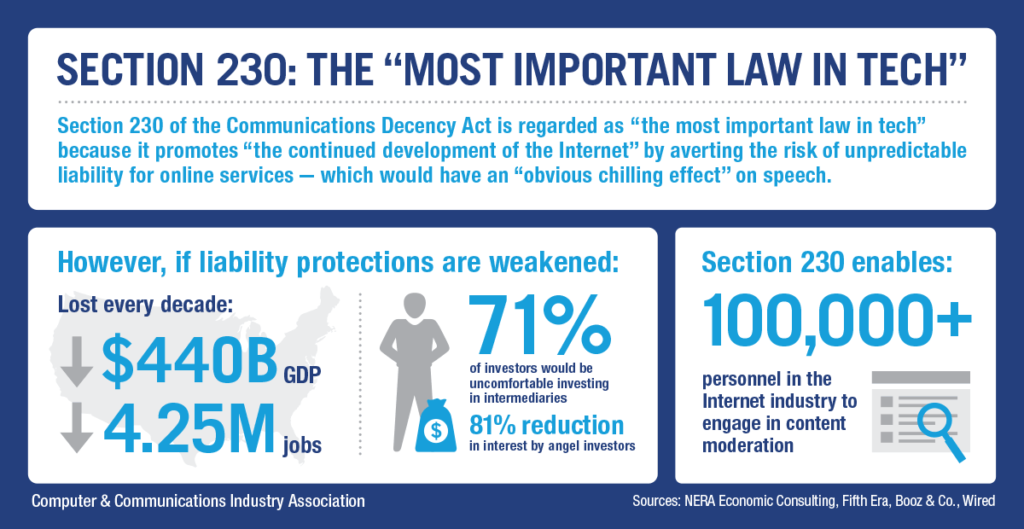

Meanwhile, the tech giants themselves have been fighting to hold back any and all regulation, as shown in this public relations piece from the Computer and Communications Industry Association

Meanwhile, the tech giants themselves have been fighting to hold back any and all regulation, as shown in this public relations piece from the Computer and Communications Industry Association

Reforming Section 230 :

In recent years, questions have come up about the proper scope of Section 230, according to a 2021 report by the Congressional Research Service. “While the law does have a number of defenders, others have argued that courts have interpreted Section 230 immunity too broadly,” the. CRS said. Over two dozen proposals in the 2019 – 2021 Congress ranged from outright repeal, to conditional immunity, to narrower exceptions allowing certain types of lawsuits. The new Congress (seated in 2021) has a few dozen reform proposals, especially:

Structure of the law: In February 2021, Democrats introduced a bill to reform Section 230. “Section 230 has provided a ‘Get Out of Jail Free’ card to the largest platform companies even as their sites are used by scam artists, harassers and violent extremists to cause damage and injury,” said Senator Mark Warner (D-Va). “This bill doesn’t interfere with free speech — it’s about allowing these platforms to finally be held accountable for harmful, often criminal behavior enabled by their platforms to which they have turned a blind eye for too long.” The proposed changes to Section 230 would not guarantee that platforms are held liable, but they would allow alleged victims an opportunity to raise legal claims without the law barring efforts in certain cases.

Clarifying the good samaritan provisions: In June of 2021, Republicans introduced a bill to provide clear guidelines about what is, and isn’t, protected by the immunity of the good samaritan provisions of the law.

Public health and falsehoods: In July 2021, Democrats introduced a bill to hold social media companies responsible for false and potentially deadly health information on the internet.

Algorithms and personal injury: In October, 2021, in the wake of the Facebook whistleblower papers, Democrats announced a bill to hold social platforms liable for personalized algorithmically targeted content that inflicts “physical or severe emotional injury.”

Some question the legal standing of such proposals: In “Why outlawing harmful social media content would face an uphill legal battle,” Washington Post, Oct 9, 2021, Jeff Kosseff and Daphne Keller write:

“Although the First Amendment allows liability for some lies — such as defamation, fraud and false advertising — lawmakers cannot simply prohibit all misleading speech,” they wrote. “The Supreme Court has been clear that laws restricting the distribution of unpopular speech raise the same First Amendment problems as laws prohibiting that speech outright.”

In September, 2022, President Joe Biden announced support for reform efforts in six key areas: competition (anti-trust); privacy; youth mental health; misinformation and disinformation; illegal and abusive conduct, including sexual exploitation; and algorithmic discrimination and lack of transparency.

Content moderation laws in other countries may provide some guidance, according to the Brookings Institute, a non-partisan Washington policy analysis “think tank.” In some countries, such as India, immunity over third party content is conditional to an internet company’s compliance with regulations.

A commentator from the Cato Institute (Scott Linicome) said: “The whole thing was and remains a giant mess, and in my opinion the actions of Twitter/Facebook are stupid for myriad reasons…” Meanwhile, a more sober analysis is found in the GMU / Scalia Center Report on 230

The Facebook papers

In late September of 2021, allegations surfaced that Facebook knew that its policies and algorithms were stoking violence and hatred, but also knew that this increased user “engagement” and therefore profits.

These papers and allegations came mostly from former Facebook employee Frances Haugen, who testified on October 5, 2021, before a US Senate sub-committee on Consumer Protection, Product Safety, and Data Security, saying:

“The company’s leadership knows how to make Facebook and Instagram safer, but won’t make the necessary changes because they have put their astronomical profits before people. Congressional action is needed. They won’t solve this crisis without your help.”

Haugen also blamed Facebook for fanning genocide and ethnic violence in Myanmar and Ethiopia.

This is only one set of many allegations against Facebook and social media in general.

Facebook is able to deflect most proposals for reform, at least for now, because of Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act of 1996. Many of the 2021 – 22 reform proposals revolve around changing this act.

FURTHER READING

White House renews call to remove section 230 liability shield, Politico, Sept. 9, 2022.

Congressional Research Service report on CDA 230, April 7, 2021

Section 230 Reform is a Dangerous Beast to Wrangle, Washington Post, Feb. 7, 2021

Sarah S. Seo, “Failed Analogies: Justice Thomas’s Concurrence in Biden v. Knight First Amendment Institute,” 32 Fordham Intell. Prop. Media & Ent. L.J. Summer 2022, 1070.

The Center for Internet and Society at the Stanford University Law School, the Electronic Frontier Foundation, and the First Amendment Center all track recent cases in internet libel in the US.

Seaton v TripAdvisor — US 6th Circuit Court No. 12-6122 — Trip advisor cleared of defamation charges after calling the Grand Resort Hotel “America’s dirtiest hotel.”

Barnes v Yahoo, 2006 — Ms. Barnes sued Yahoo!, Inc. because (she said) the company did not honor promises to remove her phone number and nude picturese by her former boyfriend. The postings seem to have been malicious. The court said Yahoo was immunized by Section 230 of the Telecommunications Act. Of course, Ms. Barnes’ former boyfriend could be held responsible in a separate lawsuit. (See “For a good time call…”).