Laws that regulate competition, prevent monopolies and maintain a “level playing field” between industries are called Antitrust laws in the US and “Competition laws” in other English-speaking countries. Antitrust law is enforced by the US Dept. of Justice, the Federal Trade Commission and the Federal Communications Commission.

“Trust” in this context is just an older name for a monopoly, since, at one time, stocks of competing companies were “held in trust” by the dominant company.

European laws protecting competition back to the Middle Ages. In the US, antitrust laws date back to the 1890s, when state and federal legislatures began to fight monopolies in transportation, commodities, energy and communications.

Congress passed the first antitrust law, the Sherman Act, in 1890 as a “comprehensive charter of economic liberty aimed at preserving free and unfettered competition as the rule of trade.” In 1914, Congress passed two additional antitrust laws: the Federal Trade Commission Act, which created the FTC, and the Clayton Act. With some revisions, these are the three core federal antitrust laws still in effect today. — Federal Trade Commission website

The Sherman Anti-Trust Act, 1890, which outlaws “every contract, combination, or conspiracy in restraint of trade,” and any “monopolization, attempted monopolization, or conspiracy or combination to monopolize.”

A followup law, the Clayton Antitrust Act of 1914, deals with anticompetitive mergers or when sets of products are tied to other products, or when a company refuses to deal with another company for anti-competitive reasons.

Antitrust laws are intended to keep markets competitive, and when any one company completely dominates a market, courts may order it to change. For example, the Justice Department may ask, and courts may order, that the company be broken up into competing companies, or that order other remedial action be taken.

In the 2020s under the Biden administration, anti-monopoly law is back, and with bipartisan support. And a July 7, 2021 executive order showed support for ongoing anti-trust investigations and activities.

In this section, we’ll look at:

(this page)

- History of antitrust law, especially the Sherman Act of 1890 and the Clayton Act of 1914;

- Types of monopolies: horizontal and vertical integration; oligopoly and monopsony.

- Regulatory approaches: rule of reason, neo-liberal and others.

(next pages)

- Traditional media monopoly regulation: movie theaters, wire services, newspapers, broadcasting.

- Digital media monopoly regulation, especially social media (Facebook, Twitter, etc) and the digital giants (Microsoft, Google, Amazon and Apple).

- Telecommunications monopoly regulation, especially Verizon and AT&T, and the fight over municipal broadband.

1. A quick history of anti-trust law:

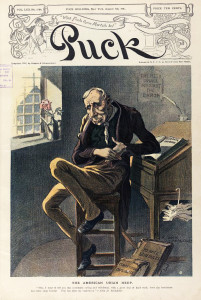

John D. Rockefeller was one of the most hated men in America a century ago, in part because he tried to gloss over his grossly underhanded business techniques with false piety and cloying humility. Here Puck Magazine compares him to Uriah Heep, a character from Charles Dickens book David Copperfield.

The Sherman Anti-Trust Act of 1890 outlawed monopolies and monopolization. The law also said that any contracts, combinations or conspiracies in restraint of interstate trade were illegal. In addition, it awarded triple damages to claimants and gave regulatory powers first to the Justice Dept. and (after 1914) to the Federal Trade Commission.

The Sherman Act passed Congress in 1890 almost unanimously. The bill’s author, US Senator John Sherman said, “If we will not endure a king as a political power we should not endure a king over the production, transportation, and sale of any of the necessaries of life.”

The Sherman Act was inspired (in part) by the dominance of Standard Oil Co. It resulted in the breakup of oil, tobacco and other monopolies. The landmark case was U.S. v. Standard Oil, 1911, which broke Standard up into companies now known as Exxon (a.k.a. Esso, Standard of New Jersey), Chevron (aka Standard of California), Sohio (aka Standard of Ohio), Mobil (Standard of New York), Amoco (Standard of Indiana) and others.

Standard Oil Co. was involved in a host of illegal activities designed to control the market. For example, Standard bribed accountants from competing firms so that John D. Rockefeller knew their exact financial breaking point. They dumped badly made products under their competitors brand names, in hope of steering customers towards them. They refused to deal with firms that they didn’t like, as in the Ethyl Gasoline Corp. case where owners Standard and General Motors were found guilty of conspiring to keep alternative fuels off the market in the 1930s.

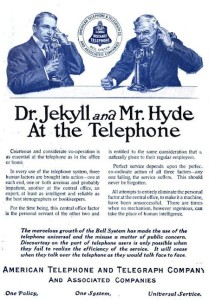

The AT&T case — Around 1908 the Justice Department started investigating telephone and telegraph monopolies. AT&T — by now a combination of Western Union telegraph and Bell telephones — mounted an unprecedented public relations campaign that successfully argued that they were “natural” monopolies that benefitted consumers. Notice in the ad to the right, the bottom line: “One policy, One system, Universal Service.” The US government let AT&T off the hook with the Kingsbury Commitment in 1912, but finally, in 1982, forced the monopoly to break up. After the breakup, the “baby bells” recombined and merged together. By 2022, a new set of monopolies and near-monopolies dominated media and telecommunications.

The Clayton Anti-Trust act — 1914 — This law clarified and superseded Sherman and expanded enforcement. Business practices as well as market domination may be the subject of antitrust enforcement. Tying arrangements (having to buy one product to get another) and refusal to deal (not selling to those who buy from competitors) are among the behaviors prohibited.

Also: The Celler-Kefauver Act of 1950 prohibits buyouts and mergers when result is more monopoly and less competition. Example: Longstanding proposals for a merger between satellite TV providers Dish and DirectTV have been blocked several times by the FCC, most recently in 2020.

2 Background: Types of monopolies:

- Horizontally integrated — One company might own one segment of the industry across the board — Example: All the oil refineries, or all the film studios.

- Vertically integrated — One company could own everything from raw materials to final markets– Example: From oil wells to refineries to pipelines to gas stations; or from script writing to film studios to distribution to theaters.

- Oligopoly — a small number of firms control a market. Example: Microsoft has an 80% near monopoly over operating systems. Viacom, Time-Warner, Bertlesman and Sony own large portions of the broadcast media market. Verizon and AT&T own most of the cell phone, DSL and fiber optic broadband market. Charter and Comcast dominated cable TV and cable broadband.

- Monopsony –– A “buyer’s monopoly.” For example, a monopsony situation would be a mining town where the mining company is the only major employer, and can set low wages. The Justice Department has argued in 2022 that the merger of Penguin Random House and Simon & Schuster would create a monopsony.

Monopolies and oligopolies obviously mean less competition, but what does that mean for you?

If you live in an inner city, a small town or a rural area, chances are you have one company providing cable and another company providing phone service, and both companies providing low-tech broadband. Phone company DSL is so slow as to be nearly useless ( 2 mbs) but still expensive ($80/month). A cable company is the other option, with cable broadband (perhaps 150 mbs) much faster, but at about double the cost. Both are unreliable; typically, the phone and cable lines are so old that that service drops out in the rain. Neither phone nor cable company has any competition, although a different cable company may operate in the next city or county over, and a different phone company may operate in a nearby region.

So the fact that there are other companies doesn’t mean the companies are competing. The FCC does not oppose this sort of anti-competitive behavior. And the price keeps going up.

Meanwhile, neither your phone company nor your cable company has plans to provide fiber optic cable to your neighborhood, but at the same time, both are fighting legislation to allow municipal broadband networks, organized by local and regional governments.

This is one way that telecommunication monopolies affect you directly.

3 Regulatory philosophy

One question dogs the antitrust debate: Who is hurt by monopolies? There’s no question that monopolies can hurt other businesses. But do they always hurt consumers or the public interest?

The conservative approach was that consumers may get a better deal from a big company. The conservative argument was called the “rule of reason.” For example, in 1911, Standard Oil argued (unsuccessfully) against a court order to breakup its system, saying that they provided a cheaper and safer kerosene fuel than would have been available on the market. The courts held that to be untrue. However, in 1912, AT&T said universal phone service was a better deal for consumers, and the Justice Dept. agreed.

So the conservative philosophy was that some business consolidations are pro-competitive, and should be encouraged, while others are not, and should be discouraged. Example: If newspapers or radio stations are failing financially, their joint operating agreements or mergers could be seen as pro-competitive as they struggle to compete with other media. Another aspect of the rule of reason is the failure of the law to anticipate the dynamism of the marketplace. For instance, IBM had a “per se” monopoly, and faced an antitrust suit, during the years it was collapsing as the personal computer took over the market.

The mainstream liberal approach is the opposite of the neo-conservative position, and it dominated the Supreme Court from the 1930s through the 1970s and the Warren court. The liberal approach favors regulation and uses the per se test. Market dominance is in itself evidence of anti competitive behavior. For example, if Microsoft has 90 percent of the market, it is per se a monopoly, and it must divest (sell off) corporate divisions into new competitive companies. (As of 2021, Microsoft and Intel owned 80 percent of the computer market).

So mainstream liberals see antitrust as a necessary market correction. The market can regulate resources, and when it works, we should leave it alone, according to the mainstream liberal philosophy. But some activities aren’t well regulated by the market.

Neo Conservative (aka Chicago School) — 1970s to 2020s — The market is superior in most cases. The role of government here is to step in with very light regulation, such as enforcement of contracts and stopping deceptive trade practices, and protect consumers against obvious harm. But otherwise, government should keep a hands off attitude, since the market tends to be self correcting. If companies get too big they will divest on their own. One example is the shift from big computers to personal computers, and the loss of market by IBM (which dominated computing until around 1980) to small computer companies like Microsoft and Apple in the 1980s and 1990s.

New Brandeis movement — A liberal / progressive movement opposing Chicago-school dictates and appreciating the antitrust philosophy of Louis Brandeis, who, before reaching the Supreme Court, advised President Woodrow Wilson in the election of 1912 to condemn “the curse of bigness” and favor breakups of those trusts that the Sherman Act had yet to dismantle. (From The Nation, April 4, 2017).

Current atmosphere — President Biden’s FTC Chair, Lina Khan, said she would prioritize harms to consumers from anticompetitive corporate behavior. Her interpretation of this includes situations where prices may be temporarily lower due to lack of competition, putting her in the neo-liberal camp. She is particularly concerned with online giants, especially Amazon. Her 2017 Yale Law Journal paper, “Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox,” points out that Amazon is willing to forego short term profits in order to establish long-term dominance over a large number of markets.

Google case — September – November, 2023 — The Justice Dept. presents the first modern era antitrust case against Google, arguing that the tech giant had paid Apple and other tech platforms over $10 billion a year to be the default search engine. (See US v Google LLC)

Facebook (Meta) case — A similar case is being prepared for trial in 2024 by the Federal Trade Commission.

Amazon and Apple cases — In 2024, the Justice Dept. and the Federal Trade Commission brought antitrust cases against Amazon and Apple.

EU cases — The EU has pursued half a dozen antitrust (competition law) cases against Google and other tech giants, but is now taking a more direct approach in 2023 with the EU Digital Markets Act. For example, see “EU targets Apple, Amazon, Meta,” Associated Press, Sept. 6, 2023.

The modern monopoly problem

Excessive concentration of financial power leads to unemployment, high costs for essentials like prescription drugs, and failing farms and small businesses, according to the Institute for Local Self Reliance.

Corporate concentration has reached a level today not seen since years before the Great Depression, when industrial monopolies dominated the American landscape and the American economy, the ISLR says.

Consider this:

- We’ve lost 65,000 small independent retailers in the last decade. Walmart accounts for one in four dollars that Americans spend on groceries and captures more than half of grocery sales in 43 metropolitan areas.

- One in three local banks has disappeared over the last ten years, leaving one-third of U.S. counties without a local financial institution. On Wall Street, four big banks control more than $7 trillion in assets, or 41 percent of the assets of the entire U.S. banking system.

- Amazon, Google, and Facebook have become powerful online gatekeepers that control a growing share of our commerce, news, and information. Some 2,000 counties now lack daily newspapers, a trend that is in part a result of Google and Facebook’s appropriation of digital ad dollars.

Monopolies hurt consumers and the market.

- They undermine small business

- They create unemployment and low wages

- They kill innovation

- They destabilize communities