Outline of advertising law section:

- 7.1 Introduction (this page)

- 7.2 History of US advertising regulation in the 20th century

- 7.3 Advertising case law

- 7.4 Current advertising regulation:

- US agencies with jurisdiction over advertising (FTC, FDA, USDA, SEC)

- Major laws regulating advertising

- UK agencies with jurisdiction over advertising

- 7.5 Deceptive advertising

- 7.6 FDA and Dopesick

- 7.7 Alcohol ads

- 7.8 Tobacco ads

- 7.9 Children’s ads

- 7.10 Public media ads

- 7.11 Signage

- 7,12 Corporate speech

- 7.13 International Ads

When Purdue Phrama company launched OxyContin in 1996, ads and sales representatives told doctors that it was safe for back aches, knee pain and other common conditions. The claimed, falsely, that it was less addictive than other prescription opioids.

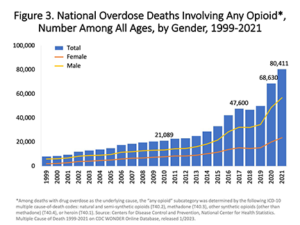

The result has been an epidemic of opioid abuse and death. From 1999-2022, over 725,000 people died from overdosing on opioids.

The Food and Drug Administration is supposed to regulate advertising for medicine with the rigor that would avoid needless deaths from these helpful but potentially lethal products. Yet, in one of the worst lapses of regulatory oversight in history, the FDA’s regulation of Purdue Pharma‘s OxyContin did not control false and malicious advertising.

FDA came under scathing criticism for allowing Purdue Pharma to flood the market with lethal pain pills and lie about their non-addictive qualities. According to the American Medical Association’s Journal of Ethics: “The fact that opioid manufacturers disseminated false claims regarding the risks and benefits of opioids for the past 25 years points to a dereliction of duty by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)—the federal agency charged with regulating pharmaceutical companies.”

See Section 7.6, FDA and Dopesick

Introduction

The law of advertising and public relations involves the entire spectrum of communications law, from fully protected speech to highly regulated speech, depending on the content and venue. The law has also undergone a full arc of historical change over the 20th century, from absolutely unregulated, to fully regulated and unprotected, to (most recently) partly regulated and partly protected.

General issues

At the beginning of the 20th century, advertising was almost entirely unregulated — so much so that ads for quack cancer cures, cocaine tonics and opium-based syrups were perfectly legal. “Muckraking” journalism campaigns against “patent medicines” led to the creation of laws regulating foods, drugs and advertising in the 1906 – 1914 Progressive era.

Courts upheld full advertising regulation in the early to mid-20th century on the “hierarchy of speech’ theory, viewing political speech as fully protected by the First Amendment, commercial speech on a second tier, and indecency and obscenity as more or less unprotected (although not necessarily illegal).

This hierarchy began changing with issue-oriented advertising in the 1960s, especially with the New York Times v Sullivan case in 1964. Then, in the 1970s, courts heard cases involving generic drug advertising, abortion, legal services and energy conservation and often found that there were political dimensions within the commercial proposition. For example, the idea that seniors had the political right to learn about generic medicine (Virginia Board of Pharmacy v Virginia Consumers Council, 1976) had a political as well as commercial dimension.

So gradually, between 1964 and the 1990s, the theory of a First Amendment hierarchy of protected speech began to erode. Advertising in most cases was as well protected as political speech, since in many cases it did have a political dimension. This was a trend towards deregulation.

Special areas of regulation

Deregulation might have been advisable in some general product areas, but in special advertising areas, such as medicine, liquor, tobacco, children’s advertising, and ads for financial services, the trend towards deregulation has been questioned and in some cases reversed.

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC); the Food and Drug Administration (FDA); the Federal Communications Commission (FCC); and the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) have all found that high costs and sometimes loss of life have followed deregulation in some areas of federal responsibility.