What happens when a sharp, off-color comment pierces the thin skin of a president? Stephen Colbert struck a nerve with his May 4, 2017 comic monologue about then-president Donald Trump’s mouth being Russian dictator Vladimir Putin’s “cock holster.” The day after, the FCC received several thousand complaints and announced it would look into the issue.

The FCC could have imposed serious financial penalties for profane or indecent political speech under regulations that apply to over-the-air broadcasting. But the mare’s nest of regulations (see the FCC site) don’t apply to print or the web, and usually don’t apply to cable.

Then-FCC Chair Ajit Pai said the agency would apply the “obscenity” standard from Miller v. California. This would be a less stringent standard, and it would be used because the Colbert show airs after 10 p.m., which is within the “safe harbor” (see FCC v Pacifica Foundation, 1978).

Still, by May 23, the FCC decided there would be no fine in the Colbert case. (The supposedly offensive political commentary begins around 11:00 minutes into the video.)

Longstanding debate

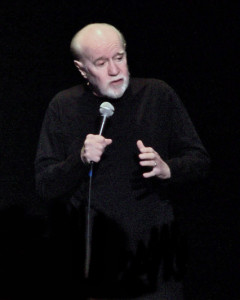

George Carlin’s “Seven Dirty Words” (Warning: Not for children) comic monologue was the subject of the FCC v. Pacifica Foundation case of 1978. In the end, the court supported the FCC’s restrictions on indecency (as opposed to obscenity). Indecent content, the FCC said, would be restricted to a “safe harbor” between the hours of 10 p.m. and 6 a.m. A similar comedic sketch on Britain’s Office of Communication (OfComm) is found here.

Obscenity laws are concerned with prohibiting lewd, filthy, or disgusting words or pictures, and there are major disagreements as to what is or isn’t obscene and what role the government should play in enforcing social or cultural morals. All fifty states have laws to control obscenity. Virginia’s obscenity statute is typical of most states, using language from the Miller v California decision (1973). It defines obscenity as:

“… that which, considered as a whole, has as its dominant theme or purpose an appeal to the prurient interest in sex, that is, a shameful or morbid interest in nudity, sexual conduct, sexual excitement, excretory functions or products thereof or sadomasochistic abuse, and which goes substantially beyond customary limits of candor in description or representation of such matters and which, taken as a whole, does not have serious literary, artistic, political or scientific value.”

The Supreme Court has consistently held that the First Amendment does not protect everything. Materials that are declared legally obscene are not protected; they may be censored and creators and distributors may be punished, sometimes with jail sentences.

On the other hand, materials or expressions that are indecent may be restricted in terms of time, place and manner, but are still protected by the First Amendment.

One issue is how, exactly, can we distinguish obscenity from indecency? The definitions are foggy and have changed over time. Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart famously said (in Jacobellis v. Ohio, 1964 ):”I shall not today attempt further to define the kinds of material I understand to be embraced … but I know it when I see it….” Stewart’s dilemma illustrates the difficulty for the courts in clarifying the ground rules for obscenity.

Gloria Steinem, a feminist scholar and writer, once made a salient point about the problem behind obscenity: “Sex is the tabasco sauce that an adolescent national pallet sprinkles on every dish on the menu.”

It’s important to remember that real lives and livelihoods are at risk in obscenity cases. Between the 1870s and the late 1950s, many thousands of printers, booksellers, writers, artists, dancers and speakers went to jail as a result of obscenity laws. Moral crusader Anthony Comstock even bragged about the numbers he had jailed in the 19th and early 20th century. One New York bookseller, Sam Roth, was sentenced to seven jail terms in the 1950s, including two 3-year terms, for selling books that would hardly raise an eyebrow today.

Inconsistency in the law

Decisions by local, state or federal authorities to suppress obscene or indecent materials are rarely consistent. Sale of materials that might have been met with a small fine in one state, or in one decade, could lead to long jail terms and heavy fines in another state or another decade.

One interesting example of this inconsistency in the law involves the attitude towards partial nudity in official symbols. The seal of the state of Virginia, which shows the Roman Goddess Virtus dressed in amazon garb standing over the body of a tyrant, had an exposed breast when it was designed in1776. During the Civil War, the exposed breast was covered by the Confederate government. Afterwards the original seal was replaced.

An interesting sidelight was a protest that took place at the state capitol in Richmond, Va. in February, 2019, involving an artist’s re-creation of the Roman goddess Virtus on the state seal. State Police arrested Michelle Renay Sutherland and held her on a charge of indecency, but prosecutors dropped the charges in early March.

A short legal history of obscenity

Obscenity and pornography are found in many cultures dating back millennia, but have usually kept from public view. For example, some of the statuary and frescoes preserved under the ashes of the Roman city of Pompeii were so explicit that they were kept in back rooms of royal museums and were seen only by gentlemen who paid an additional fee.

Until the 1700s, the church might persecute obscene books and engravings in ecclesiastical courts. In Protestant England such courts were more concerned with politics than morality, and when Fanny Hill: Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure by John Cleland was first published in 1749, British authorities took no notice. Trade in erotic literature grew in the 19th century. London’s Holywell Street, known as Bookseller’s Row, was the home of 57 porn shops by 1834.

In the 1830s and 40s, London’s Society for the Suppression of Vice, (with branches in many cities) pushed for laws that gave magistrates authority to issue warrants to seize and destroy obscene materials. Prosecution of “obscene libel” also became common as the law increasingly recognized a problem in the Victorian era. “Pollution” of the environment, especially sewage and industrial runoff, was often equated with the “moral pollution” from Booksellers Row.

In the 1830s and 40s, London’s Society for the Suppression of Vice, (with branches in many cities) pushed for laws that gave magistrates authority to issue warrants to seize and destroy obscene materials. Prosecution of “obscene libel” also became common as the law increasingly recognized a problem in the Victorian era. “Pollution” of the environment, especially sewage and industrial runoff, was often equated with the “moral pollution” from Booksellers Row.

The case that set the Victorian era standard for obscenity was:

Regina (Queen) v. Hicklin (1868 L. R. 3 Q. B. 360)

The context of R. v Hicklin is the enforcement of the 1857 Lord Campbell Act, which set a standard for obscenity in Britain. The law wasn’t tested until 1868, when bookseller Henry Scott was brought up on charges for a lewd anti-Catholic pamphlet called “The Confessional Unmasked,” a piece of crude anti-Catholic propaganda that was part of the social turmoil around the Murphy Riots.

Scott appealed to Benjamin Hicklin, a recorder in London, and although Hicklin ruled in Scott’s favor because his intention was to argue about religion, not to deprave morals. The ruling was later overturned by Alexander Cockburn, Britain’s chief justice, who said the law did not turn on the intentions of the creator or distributor of obscene materials, but rather on the effect on readers:

“The test of obscenity is whether the tendency of the matter charged as obscenity is to deprave and corrupt those whose minds are open to such immoral influences and into whose hands a publication of this sort may fall.”

So: Bad tendency — most susceptible — any small part of the work — These are the elements of the Hicklin Rule.

This Hicklin Rule was cited in American court cases in the 1800s and early 1900s. The rule allowed a publication to be judged for obscenity based on isolated passages of a work considered out of context and judged by their apparent influence on most susceptible readers, such as children or weak-minded adults. The Hicklin rule was the legal foundation of “Comstockery” in America

Comstock and the suppression of vice in the US — 1870s to 1930s

After the Civil War. reform movements of many kinds emerged. Some we look back on with a certain pride, for example, the women’s suffrage movement that led to women’s voting rights; or the environmental movement, which had origins in the desire to preserve and protect life. One of the least attractive of these reform movements was the anti-obscenity movement headed by Anthony Comstock— a crusading moralist devoted to strict ideas of Victorian morality and censorship. (Comstock’s story is told in a 2021 book, “The Man Who Hated Women.”)

After the Civil War. reform movements of many kinds emerged. Some we look back on with a certain pride, for example, the women’s suffrage movement that led to women’s voting rights; or the environmental movement, which had origins in the desire to preserve and protect life. One of the least attractive of these reform movements was the anti-obscenity movement headed by Anthony Comstock— a crusading moralist devoted to strict ideas of Victorian morality and censorship. (Comstock’s story is told in a 2021 book, “The Man Who Hated Women.”)

In theory, the definition of obscenity in the US rested on the state level. For example, Massachusetts censors banned books like Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure as early as 1821. And the US Tariff Act of 1842 was the first federal law restricting imports of obscene material. It didn’t have much effect, and as the Victorian era dawned in America in the wake of the Civil War, Comstock and other crusaders set about improving America’s moral posture.

The Comstock Laws

In 1873, Comstock lobbied Congress to pass a “decency” bill which outlined a wide range of moral guidelines and penalties for any sexually oriented publication, including information about family planning, abortion, venerial disease, contraceptives or sexual issues of any kind. Even a printed discussion of birth control was obscene and therefore not protected by the First Amendment.

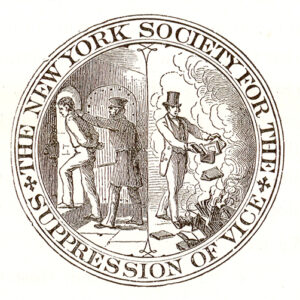

Comstock was named a special agent of the Post Office and given free transportation to go wherever he wanted and enforce the law that carried his own name. He bragged later that he was responsible for sending enough people to jail to fill a 61 coach passenger train.

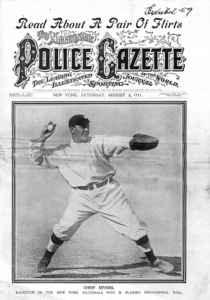

Comstock’s own New York Society for the Suppression of Vice and the Boston Watch and Ward Society were two of the leaders. If you ever hear the phrase “Banned in Boston,” you may find it interesting to know that this is the group that had it banned. Among things they banned over the years: Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass (in 1882); Bocaccio’s The Decameron and Rabelais’ Gargantua and Pantagruel (Renaissance era books banned in 1903); Elinor Glyn’s Three Weeks (in 1907); The National Police Gazette (1911); Robert Keable’s Simon Called Peter (in 1922 ); Floyd Dell’s Janet March (in 1923).

Most famously, the Watch and Ward Society banned Herbert Asbury’s short story Hatrack, published in H.L. Mencken’s American Mercury (1926) which led to Mencken’s arrest. As Steve King wrote in a 1956 Saturday Evening Post article, “H.L. Mencken and the Booboisie:“

H.L. Mencken, a Baltimore Sun columnist and editor of the American Mercury, was an acerbic critic of the American political scene. He called the people promoting laws against obscenity the “Booboise,” combining the idea that they were intellectual “boobs” with the French word for middle class people, the bourgeoisie .

Mencken’s most famous literary battle was fought in 1926, over a forgettable short story he published by Herbert Asbury, entitled “Hatrack.” Hatrack was a small-town prostitute whose efforts to reform were indignantly rebuffed. It became her habit to take her Catholic clients to the Protestant cemetery, and vice-versa. The punch line of the story occurs when one of her customers tenders Hatrack a dollar, to which she responds, “You know damned well I haven’t got any change.”

Victoria Woodhull as the devil with her free love doctrine is depicted trying to lure a woman with an alcoholic husband and a crying baby down the path, and away from salvation. (Thomas Nast, 1872)

Reverend Chase of The New England Watch and Ward Society was not amused. He managed to get Mencken’s magazine pulled from newsstands in the Boston area, and he threatened legal action if there were further attempts to sell it. This was a line that Mencken managed to cross in dramatic fashion. He contrived to meet with Chase on Brimstone Corner of Boston Common, with the vice squad and a clutch of photographers in attendance. Mencken sold Chase the magazine and got carted away, but not before getting his picture taken biting Chase’s half-dollar to test it, as Hatrack would have done. The next day the judge ruled in Mencken’s favor, and the case became a small landmark in the campaign for literary freedom, and in Mencken’s headline-grabbing career.

Although its influence began to decline in the 1920s, the Watch and Ward society continued to black list books and movies, among them: Aldous Huxley’s Point Counter Point, Voltaire’s Candide, Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front; Theodore Dreiser’s An American Tragedy; John O’Hara’s Appointment in Samarra; Lillian Hellman’s play The Children’s Hour; and, as late as 1950, Erskine Caldwell’s God’s Little Acre.

Comstockery was not only concerned about publications with dirty pictures. Comstock and other social conservatives of the era worried that the women’s suffrage movement (to give women the vote) and new ideas about women’s rights were undermining American morality. Indeed, propaganda against suffrage workers like Victoria Woodhull was fairly typical. In one Thomas Nast engraving, we see Woodhull as the devil with her “free love” doctrine trying to lure a woman with an alcoholic husband and a crying baby moving down the path away from salvation. By “free love“, Woodhull meant the freedom to marry, divorce and bear children without social restriction or government interference.

In 1914, Margaret Sanger published the Woman Rebel, which included frank discussions about contraception, and was indicted for violating the Comstock Acts. The newspaper was banned and Sanger was indicted for violating postal obscenity laws. She faced a potential 45 years in jail, but went into exile in England for several years. When the laws changed several years later, she returned to open clinics and continue her advocacy through a group that eventually became known as Planned Parenthood.

The women’s movement reacted to “Comstockery” by insisting on a free speech right to discuss birth control. In 1914, Margaret Sanger published the Woman Rebel, which included frank discussions about contraception. She was indicted for violating the Comstock Acts, although the charges were dismissed by the 1920s. Sanger’s ideas about free speech and birth control seem admirable in the modern context, but other ideas do not. For example, she hoped birth control could be used to keep the “Nordic” races from being overwhelmed by other races that she considered inferior. In this she was a woman of her times, subject to (and supporting) some of the social evils that were accepted in their day.

To be sure, even simplest, most basic information about birth control continued to be illegal in the US and Canada until the late 1960s. One group of McGill University students who hoped to inform women about their rights and options published the illegal “Birth Control Handbook” in 1968. Two years later the Boston Women’s Health Collective published Our Bodies Ourselves.

The long arm of federal censorship

** Mutual Film v. Industrial Commission of Ohio, 1915 — Ohio set up a system of board of censors which, by law, could only approve films that were “of a moral, educational, or amusing and harmless character.” The law was upheld and, on appeal, the Supreme Court said that the state has an interest in public morals and that films “may be used for evil.” Noting that audiences were made up of both adults and children, the court said that “a pretense of worthy purpose” might make films “even more insidious in corruption.” Freedom of speech does not apply to spectacles and circuses, the court said. It is interesting that the court considered the state constitution’s guarantee of free speech here and not the US Constitution’s First Amendment. Following this decision, the system of censorship continued on a national level through the Hays Committee and the Motion Picture Association of America through the 1960s, then changed to the current rating system: G, PG, PG-13, R and NC-17. The Mutual Film decision was overturned in Burstyn v Wilson, 1952. (Below)

One Book Entitled Ulysses v. US, 1933, One of the most frequently censored books of the early 20th century, Ulysses (by James Joyce) was finally brought to trial in 1933. Judge John Woolsey found the book not obscene, and his decision in the case did not apply the Hicklin Rule, which was the standard at the time. One aspect of the Hicklin Rule stated that in order to determine a work’s obscenity, its effects on the most susceptible members of society had to be determined. In Ulysses v. US, Woolsey said that instead of the most susceptible members of society, its effects on the average person determine a work’s obscenity. Where the Hicklin Rule allowed for a work to be judged by individual passages, which could be easily taken out of context, Woolsey based his judgment on the work as a whole. The case was appealed, but the Appeals Court upheld Woolsey’s decision, and in effect the Hicklin Rule was abolished in the US on the federal level.

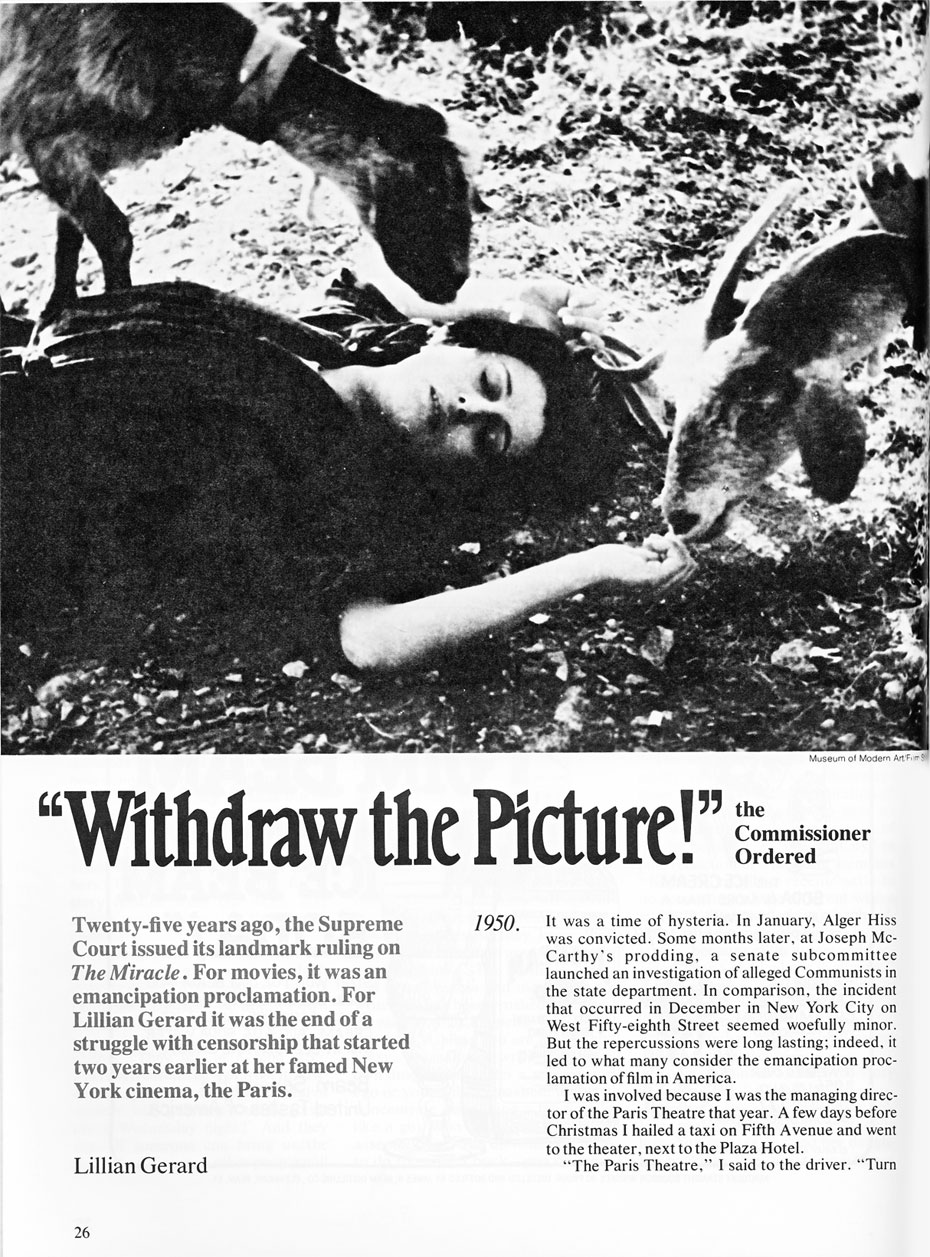

** Joseph Burstyn Inc. v Wilson, 1952 — A landmark case in which the Supreme Court said that film was an artistic medium and should be given the same First Amendment rights as any other art form. The case is often referred to as the Miracle Decision, since the European film in question, written by Roberto Rossellini, involves a young farm woman who may (or may not be) a little off balance. She meets a wandering vagabond (played by Federico Fellini, who also directed) and thinks that he is Saint Joseph. She wants to take him away to paradise. He gives her a drink and she falls asleep. The next day, he’s gone, and soon she is pregnant. She is driven from her town, and in the course of time, gives birth to a child that she believes is the son of God.

** Joseph Burstyn Inc. v Wilson, 1952 — A landmark case in which the Supreme Court said that film was an artistic medium and should be given the same First Amendment rights as any other art form. The case is often referred to as the Miracle Decision, since the European film in question, written by Roberto Rossellini, involves a young farm woman who may (or may not be) a little off balance. She meets a wandering vagabond (played by Federico Fellini, who also directed) and thinks that he is Saint Joseph. She wants to take him away to paradise. He gives her a drink and she falls asleep. The next day, he’s gone, and soon she is pregnant. She is driven from her town, and in the course of time, gives birth to a child that she believes is the son of God.

** Roth v. US, 1957 — New York city bookstore owner and poet Samuel Roth was arrested on federal obscenity charges. Roth’s appeal went to the US Supreme Court, which said that obscene materials were not protected by the First Amendment. The Roth standard formally replaced Hicklin Rule. Under Roth, obscenity is defined this way:

“Whether to the average person, applying contemporary community standards, the dominant theme of the material taken as a whole appeals to the prurient interest.”

The Supreme Court was not entirely happy with this definition, and would tinker with it for many decades. But once the federal standard had changed, strict state standards could be challenged. The first of these was in the famed “Howl” trial.

San Francisco court room is full in the 1957 obscenity trial of Alan Ginsburg’s poem Howl, published by City Lights.

The ‘Howl’ obscenity trial — In March of 1957, when the US Supreme Court was hearing the Roth case, San Francisco prosecutors brought Allen Ginsburg and Lawrence Ferlinghetti up on state obscenity charges for publication of the long poem: “Howl.” The Roth case was decided by the Supreme Court in June, 1957, before the Howl trial began in September, and so the federal Roth standard was used in the state Howl case. After considering the evidence, using the Roth standard, Judge Clayton Horn found Ginsburg and Ferlinghetti not guilty. Although the case was not precedent-setting in a legal sense, it had a major impact on public opinion and was the first time the Roth standard was applied by a state court. The Howl decision also encouraged the re-opening of other cases where judges had found books obscene, particularly D. H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterly’s Lover and Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer. (For more information, see this First Amendment Center article; Also, a 2010 film starting James Franco depicts the trial.)

Here is part of Judge Horn’s opinion:

The freedoms of speech and press are inherent in a nation of free people. These freedoms must be protected if we are to remain free, both individually and as a nation… These guarantees occupy a preferred position under our law to such an extent that the courts, when considering whether legislation infringes upon them, neutralize the presumption usually indulged in favor of constitutionality.

* Smith v. California, 1959 — A bookstore owner who did not know (or had no reason to know) about obscene materials, was not guilty of knowingly selling obscene material. The case expanded the test of “scienter” (guilty knowledge) and averted a chilling effect on distributors who might not know about the contents of materials they handled. It would become an important case as the responsibilities of Internet Service Providers were considered in the 1990s.

Meanwhile in Britain, an attempt to codify old Victorian moral codes in a 1959 law went down to defeat in a watershed 1960 trial over D.H. Lawrence’s book Lady Chatterly’s Lover. The book was badly written and not deserving of the defense it got at the trial, argues Peter Hitchens in this 2018 essay.

The Sixties and Obscenity

As late as the 1950s and 1960s, obscenity could be defined by local and state governments as the use of dirty language rather than any appeal to sexual interest. The freewheeling 1960s and 70s changed many aspects of American and European culture, and comedians were on the vanguard of the change.

Lenny Bruce

Lenny Bruce (1925-1966) and his wild, caustic, hilarious routines challenged old concepts of morality and inspired George Carlin, Chris Rock and many others. Bruce was convicted of obscenity many times in city and state courts, and spent his final years struggling with the law.

Bruce became famous for challenging taboos around language. “He had extraordinary … naivete,” said Dustin Hoffman, who played Bruce in the 1974 film Lenny. “He really felt he was going to be protected under the Constitutional [guarantee of] free speech and that what he was doing was not obscene. And it wasnt, if the defintion is to sexually arouse, that’s not what he was about.” He was convicted of obscenity at a trial in November 1964 over his act at a Greenwich Village cafe. He was pardoned posthumously in 2003 following efforts by author Rollin Collins.

Freedman v. Maryland, 380 US 51 (1965) — A film called “Revenge at Daybreak” was shown in a Baltimore theater without first submitting it to a state board of censors for approval. The court found that the censorship process was itself an infringement on the First Amendment, but found that a more timely process might be permissible. In effect, the decision was the end of outright state censorship of nationally distributed films.

* Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure v. Massachusetts, 1966 — This involved a book written in 1749 about prostitute Fanny Hill. The Supreme Court said it was not obscene, used this three part test:

- Roth test (average person, community standards, dominant theme, prurient appeal).

- Had to be patently offensive

- Had to be utterly without redeeming social value.

The bottom line: a work could not be considered obscene if it had any redeeming social value of any kind whatsoever. After Memoirs, the court began upholding time place and manner restrictions rather than firming up content tests. Note that Miller (below) changed the social value test.

Side note for contemporary culture connections: In the film “The People versus Larry Flynt,” this is the case that the grizzled old printer is referring to when Larry Flint says he wants to print a magazine with nude photos. The printer says: “But I could get in trouble printing these… there are laws. You gotta have some sort of text, like Playboy does.”

Ginzburg v. United States 383 U.S. 463 (1966) On June 14, 1968, Ralph Ginzburg and three corporations he controlled were convicted in a federal district court in Pennsylvania for sending through the mail three obscene publications. The prosecution said that these publications were obscene in the context of their publication, sale and attendant publicity. In finding Ginzburg guilty, the trial judge applied the obscenity standards first used in the Roth v. U.S. case. Evidence that the petitioners deliberately represented the material as erotically arousing and commercially exploited them as erotica solely for the sake of prurient appeal amply supported the trial court’s determination that the material was obscene under the standards of the Roth case.

The trial judge sentenced Ginzburg to five years imprisonment and fined him $28,000. Basically, this case upheld state laws against pandering based on erotic appeal or selling material that was considered obscene to minors even if not obscene for adults.

Stanley v. Georgia 394 U.S. 557 (1969) — A unanimous court said that the state of Georgia could not send a man to jail for private possession of pornography, even it was illegal to sell the pornography. A person has “a right to satisfy emotional needs in the privacy of his own house.” However, in 1990, however, the Court found that protection for private possession of child pornography was illegal.

** Miller v. California (1973) — New benchmark reflected political changes in the Supreme Court with new Nixon appointees. Community standards replaced national standards, and the court tried to isolate hard core pornography from expression protected by the First Amendment. This is still the main “controlling” case in defining obscenity. In Miller, the court said a work was obscene if it:

- Meets the Roth test (1957, above);

- Describes sexual conduct in a patently offensive way; and

- Taken as a whole, lacks serious literary, artistic, political or scientific value

** Pope v. Illinois, 1987 — Attendants at two bookstores in Rockford, Illinois were charged separately with violating an Illinois obscenity statute by selling allegedly obscene magazines. At the trials the jury was instructed to determine whether the magazines were obscene under the Miller test. But the judge made a mistake telling the jury that community standards were the only standards to be used.

In the 3rd part of Miller test ( which is whether the work taken as a whole lacks serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value ) the decision has to be objective, not solely based on community standards. And so, according to the Supreme Court, the initial decision was not in keeping with the First Amendment.

Pope modified Miller to the extent that “serious value” was not simply something that could be determined at the community level, but rather whether a “reasonable person” would see a work as obscene. In effect, the community standard of Miller was modified by a national perspective. In practice, it meant that prosecutors and jurors call in experts to help determine whether something has serious value.

Interestingly, Pope is one of the major cases cited in the Supreme Court oral argument over the “intentional infliction of emotional distress” charge in the Flint v Falwell case of 1987.

Broadcast indecency — See this page under broadcasting.

Obscenity and the internet / web

**** Reno v. ACLU, 1997, The Supreme Court struck down the 1996 Communications Decency Act (CDA), which they said was an unconstitutional attempt to control communications on the Internet. First, t he court said,

the Internet and the World Wide Web should be considered as having full First Amendment protection, such as the print media, and should not be regulated like radio and television broadcasting. While noting that it was within the government’s power to set “time place and manner” restrictions on obscene communications, and that obscenity did not have First Amendment protection, the court said that the CDA had problems:

Existing technology did not include any effective method for a sender to prevent minors from obtaining access to its communications on the Internet without also denying access to adults.” The breadth of the CDA’s coverage was unprecedented. Its open-ended prohibitions embraced not only commercial speech or commercial entities, but also “all nonprofit entities and individuals posting indecent messages or displaying them on their own computers in the presence of minors.” Because the CDA did not define the terms “indecent” and “patently offensive,” the statute “cover[ed] large amounts of nonpornographic material with serious educational value.” Regulated subject matter under the CDA extended to “discussions about prison rape or safe sexual practices, artistic images that include nude subjects, and arguably the card catalog of the Carnegie Library.” The court found that the law was not narrowly tailored.

Dancing and the first amendment

Although not a media law issue, some forms of dancing — ranging from topless dancing in the 1960s to lap dancing in the modern era — have been defended as artistic expressions that are worthy of First Amendment protection. The courts have backed away from direct bans, and have instead allowed local standards (Las Vegas can be different from Lexington) and time, place and manner regulations (Main street can be different from church street). In the video above, a topless bar in Roanoke, Va. met resistance in 1965. Questions about the treatment of women who perform these dances are among the human rights issues raised by exploitation in the sex trades.

Pornography as a human rights issue

Although the Roth, Miller and Pope cases more or less ended Comstockery, and the Reno case extended full First Amendment rights to the internet, controversy continues over violent pornography and its impacts. Andrea Dworkin, for example, writes in “Letters from a War Zone:”

Although the Roth, Miller and Pope cases more or less ended Comstockery, and the Reno case extended full First Amendment rights to the internet, controversy continues over violent pornography and its impacts. Andrea Dworkin, for example, writes in “Letters from a War Zone:”

I live in a country where if you film any act of humiliation or torture, and if the victim is a woman, the film is both entertainment and it is protected speech. Now that tells me something about what it means to be a woman citizen in this country, and the meaning of being second class. When your rape is entertainment, your worthlessness is absolute. You have reached the nadir of social worthlessness. The civil impact of pornography on women is staggering. It keeps us socially silent, it keeps us socially compliant, it keeps us afraid in neighborhoods; and it creates a vast hopelessness for women, a vast despair. One lives inside a nightmare of sexual abuse that is both actual and potential, and you have the great joy of knowing that your nightmare is someone else’s freedom and someone else’s fun.

Dworkin and others crafted a law that prohibited violent pornography, which was passed in the city of Indianapolis, IN in 1984 with the support of mayor William Hadnut. It defined pornography as “the graphic sexually explicit subordination of women, whether in pictures or in words, that also includes one or more of the following:

Women … presented as sexual objects who enjoy pain or humiliation; or … who experience sexual pleasure in being raped; or [are] tied up or cut up or mutilated or bruised or physically hurt, or … [are] dismembered or truncated or fragmented or severed into body parts; or … are presented in scenarios of degradation, injury abasement, torture, shown as filthy or inferior, bleeding, bruised, or hurt in a context that makes these conditions sexual; or … are presented as sexual objects for domination, conquest, violation, exploitation, possession, or use, or through postures or positions of servility or submission or display.”

The law was appealed in American Booksellers Association v. William Hadnut in 1985 and struck down by the Seventh Circuit Court as unconstitutional. The court said:

Free speech has been on balance an ally of those seeking change. Governments that want stasis start by restricting speech. Culture is a powerful force of continuity; [the] Indianapolis [ordinance] paints pornography as part of the culture of power. Change in any complex system ultimately depends on the ability of outsiders to challenge accepted views and the reigning institutions. Without a strong guarantee of freedom of speech, there is no effective right to challenge what is.

Dworkin and others responded that the Indianapolis law was not intended to censor expression but rather to protect women from violence in the production of pornography and violence caused by the consumption of pornography. Dworkin’s book, “Pornography and Civil Rights,” (pdf) presents their argument. Women’s rights advocates continue to oppose violent pornography.

Further READING

National Archives, The Comstock Act, 1873, and The anti-contraception campaign (Woman Rebel newspaper), 1914.

Music and Obscenity — The story of Parent’s Music Resource Center by Newsweek. Sept. 16, 2015.

Ross Douthat, Let’s Ban Porn, New York Times, Feb. 10, 2018.

Michelle Goldberg, How Trump helped make Andrea Dworkin relevant again, Feb. 23, 2019. New York Times.