The Espionage Act and the Schenck, Abrams & Whitney cases.

With the advent of World War I, Congress passed laws forbidding criticism of the government — the Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918. Unlike the Alien & Sedition Acts of 1798, the World War I era acts were vigorously enforced, with about 2,000 arrests and 1,000 convictions. A number of these cases were appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. Three of the cases were related to the suppression of speech in this era: Schenck, Abrams and Whitney.

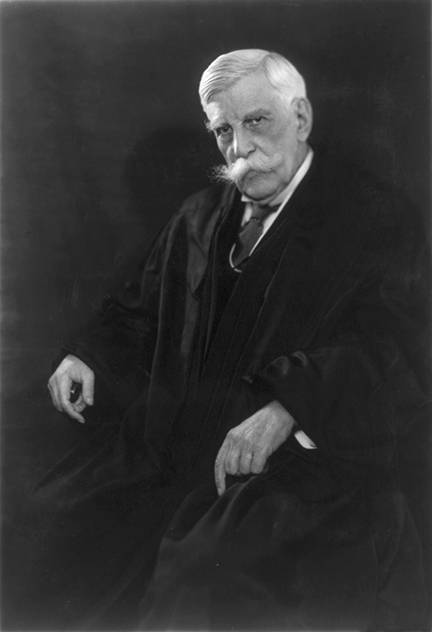

In Schenck v. U.S., 1919, the Supreme Court tested the Espionage Act and held that Socialist Party secretary Charles T. Schenck had violated the Sedition Act by circulating pamphlets to denouncing the draft as involuntary servitude. His conviction was upheld and the Supreme Court used the case to create the “clear and present danger” test of when speech could lawfully be suppressed. Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes used a famous analogy: “Free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting ‘fire’ in a theater and causing a panic.”

In two other related cases, some justices began a line of minority dissent which would later become the opinion of the majority. Note that in both cases, the effort is to define “clear and present danger” in more concrete terms.

Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr

In Abrams v. US, 1919, for instance, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes’ said in a dissent: “Congress certainly cannot forbid all effort to change the mind of the country … nobody can suppose that … a silly leaflet by an unknown man, would present any immediate danger …” Note that this Holmes’ dissent, and the one by Justice Brandeis (next) were influenced by Zechariah Chafee’s ideas about distinguishing between action and expression.

In Whitney v. California, 1927, Justice Louis Brandeis dissented from this trend. He didn’t think it was right to uphold the California state conviction of Charlotte Anita Whitney who was simply a member of the Communist Party. Some scholars assert that she was punished simply for being a feminist anti-racist reformer. The Supreme Court upheld her conviction and had taken no direction action:

“Fear of serious injury cannot alone justify suppression of free speech and assembly. Men feared witches and burnt women. It is the function of free speech to free men from bondage of irrational fears … Those who won our independence by revolution were not cowards. They did not fear political change. They did not exalt order at the cost of liberty…. No danger flowing from speech can be deemed clear and present unless the incidence of the evil apprehended is so imminent that it may befall before there is opportunity for full discussion. ..”

State level censorship 1920s – 1950s

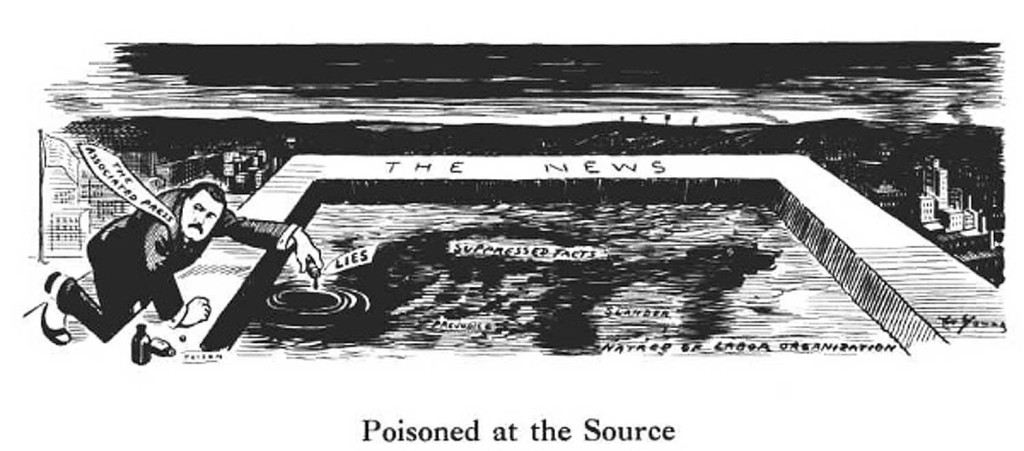

Federal censorship was not the only source of suppression of free speech and press. States were also actively involved in censorship in the post World War I era, while some news organizations exercised one-sided, heavy handed editorial directions.

Many Americans objected not only to government control of the press, but also control by monopolies such as the Associated Press. In this 1914 cartoon, published in The Masses, the AP news system is depicted spreading “poison” about labor unions. At the time, the newspapers in West Virginia that AP relied upon were owned by the coal industry, and in fact, their reports were strongly biased against labor. After the cartoon was printed, AP sued The Masses for libel, but dropped the suit a year later. Eventually, labor reporting from the coal fields improved and, in 1945, the AP monopoly was terminated by the. US Supreme Court in AP v US.

“Imagine going down to your local brewpub or coffee shop. You meet some friends. The talk turns to the war. You criticize the President and his wealthy supporters. Next thing you know, a couple of husky fellows at the next table grab you, hustle you out the door and down to the local police station. You are arrested on a charge of sedition. Within months you are indicted, tried and convicted. The judge sentences you to 5-10 years in prison — and off you go!” — (Montana Sedition Project )

Between WWI and the 1930s, US citizens were routinely arrested for criticizing the government. They were also arrested in some states for displaying the wrong flag (black for anarchism or red for communism). In 1923, Upton Sinclair, author of “The Jungle,” was arrested for trying to read the text of the First Amendment at a union rally. Many people (like Charlotte Whitney) were arrested merely for membership in groups regarded as “radical” by the government.

Prior restraint: Near v Minnesota

In the 1920s, a controversial group of anti-Semitic newspaper from Duluth, Minnesota were banned by the state legislature. J.M. Near’s Saturday Press was notorious for printing articles and cartoons accusing officials of corruption, protecting prostitution and being in league with the devil. In a history of the case, John E. Hartmann said:

Each issue … followed a set pattern… Sex, attacks on public officials and prominent private citizens, and vicious baiting of minority groups … Three- or four-inch headlines, revealing a new sex scandal, screamed from every page. “Smooth Minneapolis Doctor with Woman in Saint Paul Hotel,” or “White Slaver Plying Trade: Well Known Local Man Is Ruining Women and Living off Their Earnings.

The Minnesota state supreme court upheld the state “gas law,” saying that the Constitution “was never intended to protect malice, scandal and defamation when untrue or published with bad motives or without justifiable ends… Liberty of the press does not mean that an evil-minded person may publish just anything any more than the constitutional right of assembly authorizes and legalizes unlawful assemblies and riots.”

The US Supreme Court overruled the state supreme court, saying, in Near v. Minnesota:

“The fact that the liberty of the press may be abused by miscreant purveyors of scandal does not make any the less necessary the immunity of the press from previous restraint in dealing with official misconduct. Subsequent punishment for such abuses as may exist is the appropriate remedy, consistent with Constitutional privilege.”

A similar prior restraint case was Lovell v City of Griffin, 1938, in which a Georgia city’s ordinance required permission in order for anyone to distribute pamphlets in the city. The Jehovah’s Witnesses brought the case to the US Supreme Court, which said that the city ordinance was overly broad and imposed rules on all printed materials rather than regulating the time, place and manner of distribution.

At the outbreak of World War II, Congress attached a new sedition law to the Alien Registration Act of 1940. It became known as the Smith Act for its sponsor, Howard Smith. Unlike the Sedition Act of 1917, under which a thousand people were jailed, the Smith Act did not lead to any wartime prosecutions. However, after the war, the act was used to prosecute members of the Communist Party in the U.S.

In Dennis v. U.S., 1951, for example, the “clear and present danger” test was used again to uphold the convictions of 12 communist party members under the Smith Act. About 121 others were prosecuted under the Smith Act’s conspiracy provisions, and many thousands of others were prosecuted under state laws outlawing membership in any organizations that advocated violent overthrow of the government. A large number of these prosecutions were unsupported by evidence, and the McCarthy Era (named for then- Senator Joseph McCarthy) is remembered today for its “witch hunt” atmosphere.

The times were changing. In Yeats v. U.S. (1957), the Supreme Court (which now had several new members, especially the new Chief Justice Earl Warren) made a distinction between an abstract doctrine advocating overthrow of the government and actually organizing for violent action. The court, at this point, was moving away from prosecuting dissent.

End of the “Clear and Present Danger” test: Brandenburg v Ohio, 1969

The original clear and present danger test lasted until 1969, when the court, in Brandenburg v. Ohio, set a new standard for prior restraint: “imminent action.” The case involved the leader of a state Ku Klux Klan who advocated “revengence” against blacks and Jews. Brandenburg’s conviction under Ohio law was reversed, and so was the precedent set in Whitney v. California. The Supreme Court also drew on the dissenting opinions of Holmes and Brandies in Whitney and other cases in setting the new test.

In 2021, Brandenburg became a subject of intense study when incitement to riot at a rally, led by then-president Donald Trump, led to an attack on the US Capitol with five fatalities. Twitter and Facebook permanently banned Trump and several colleagues from their platform, and Amazon pulled its server links to an alt-right social media site, Parler. The New York Times asked: “Why is big tech policing speech?”

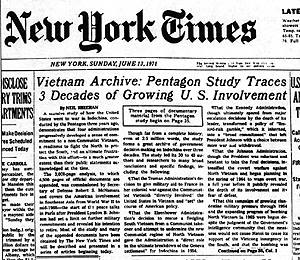

The Pentagon Papers case 1971

New York Times v. US, 1971 — President Nixon

tried to stop publication of the “Pentagon Papers,” a secret history of the Vietnam War made for the Defense Dept. The papers had been leaked to reporters by Daniel Ellsberg, a Pentagon consultant. The court said the government had a heavy burden to prove there was a national security issue, and had failed to meet it. Thus, court orders halting publication of the papers were lifted. For more about the war and the Pentagon Papers, see this Zinn Education Project page and this New York Times retrospective.

As a point of interest relative to political maneuvers against the media, Nixon attempted to take television stations away from the Washington Post Company two years later, during the Watergate crisis.

Other cases involving anti-war dissent

US v. The Progressive 1979 — The Progressive magazine of Wisconsin was going to print plans to build an H-bomb, gathered from public sources. The government asked the courts for a restraining order, and in the process of a lengthy investigation, it was found that many of the documents to be printed by the Progressive had, through carelessness, been available to the public in federal libraries. Fearful that it would lose the case, the federal government made the appeal moot by leaking documents to another publication and then stopping the prosecution.

The Flag Burning Case 1989

Of course, there have been many cases in which overly broad restrictions on speech have been struck down. Perhaps most famous are the forced speech cases and the flag burning cases.

In Texas v. Johnson, 1989, the Supreme Court said that a state law prohibiting flag burning was not constitutional because only messages of protest were being punished. Burning the flag in a respectful way (an approved method of destroying old flags) was not also being made illegal.

When Congress passed a similar law in 1990, it was struck down in US. v. Eichman. Considerable debate followed, but no law has yet been passed that will ban protest flag burning in a constitutional manner. Like many forms of dissent, flag burning makes people uncomfortable, which is the point for the protesters.

RECENT ISSUES

Anti-war protests in the US

The line between loyal opposition and outright sedition is never clear, and in US law the distinction is mostly moot. For instance, the US decision to go to war in Iraq in 2003 led to a good deal of dissent, and sometimes the dissidents were punished. Generally, their rights were upheld in state or federal courts.

For example, Laura Berg, a clinical nurse specialist with a Veterans Administration hospital, wrote a letter in September 2005 to a weekly Albuquerque newspaper criticizing the administration for Hurricane Katrina and the Iraq War. She urged people to “act forcefully” to remove an administration she said played games of “vicious deceit.” A few weeks later, the head of the Veterans Administration asked the FBI to investigate her for sedition, and her work computer was confiscated. Berg absolutely refused to back down, and by February the ACLU was suing. By March 2006 the Veterans Administration apologized and Berg was honored with a PEN award.

Terrorism and the First Amendment

Holder v Humanitarian Law Project, 2010, involved the USA Patriot Act prohibition on giving material aid to terrorist organizations. The law project was organized to give advice on international law and non-violent approaches to conflict resolution. Two groups on the US State Dept. list of terrorists, one based in Kurdistan and the other in Sri Lanka, were to be recipients of the law project’s advice, but the Supreme Court found that this would violate the USA Patriot Act.

The significance of this controversial case is that it was the first time in First Amendment jurisprudence that the “imminent action” standard was set aside and a ban on pure speech was declared constitutional.

In a 2016 test of the “Imminent action” standard, a federal judge rejected President Donald Trump’s free speech defense against a lawsuit accusing him of inciting violence against protesters at a 2016 campaign rally. The lawsuit includes a count of incitement to riot by then-candidate Trump during a campaign event in Louisville, Kentucky on March 1, 2016. The complaint alleges that the candidate told the crowd “Get ’em out of here,” when the plaintiffs were “peacefully protesting” at a campaign rally. In Nwanguma v. Trump, a federal court ruled that Trump did not advocate immediate lawless action, as would have been required for plaintiffs to succeed.

In a May 2022 test of the prior restraint standard, a federal court dismissed claims by Donald Trump that social media platform Twitter had violated his First Amendment rights by banning him for incendiary remarks at a January 6, 2021 rally that lead to a violent riot at the US Capitol. According to a Washington Post article: “U.S. District Judge James Donato rejected Trump’s argument that Twitter was operating as a ‘state actor’ when it suspended his account in January 2021, calling it not plausible. Trump had claimed that Twitter was constrained by the First Amendment’s restrictions on government limitations of free speech because it had acted in cooperation with government officials.”

US v Boulton, 2020

In June of 2020, the Justice Department filed a prior restraint lawsuit reminiscent of the Pentagon Papers. The department sued former National Security Advisor John Bolton, asking courts to suppress publication of his book about Trump’s White House.

In June of 2020, the Justice Department filed a prior restraint lawsuit reminiscent of the Pentagon Papers. The department sued former National Security Advisor John Bolton, asking courts to suppress publication of his book about Trump’s White House.

First Amendment attorney Theodore J. Boutrous said, in a June 17, 2020 Washington Post column:

“The biggest problem is that the administration is seeking a prior restraint of speech before it occurs — not just damages for injuries allegedly caused by speech after the fact. The Supreme Court has never upheld a prior restraint on speech about matters of public concern, and in the Pentagon Papers case refused to enjoin publication of a trove of classified information concerning the Vietnam War. Any prior restraint, the court explained, “bear[s] a heavy presumption against its constitutional validity.” As the court elaborated in Nebraska Press Association v. Stuart, prior restraints are “the most serious and the least tolerable infringement on First Amendment rights” and “one of the most extraordinary remedies known to our jurisprudence.”

Only a few days later, a federal court dismissed the Justice Department request for an injunction, saying that the government “has failed to establish that an injunction will prevent irreparable harm.” Other parts of the lawsuit remained active.

The Bolton case is similar to other cases in which government officials want to discuss public business but are constrained by secrecy and prior review agreements they signed when they joined the government. One of the first of these was Snepp v US, 1980, having to do with the CIA and the Vietnam war. The punishment was confiscation of Snepp’s royalties from the book.

A group of government employees filed a First Amendment suit in 2019 saying the restrictions on post-government employment publications were too strict and the standards too vague.

The Branzburg case was featured by the defense during the 2021 impeachment trial of Donald Trump for advocating violent overthrow of the US government.

Trump and the January 6, 2021 insurrection.

January 6, 2021, by Tyler Merbler, Creative Commons.

Legal opinion about then-president Donald Trump’s activities on January 6, 2021 tends to place his speech in the “imminent action” category and not protected by the First Amendment. For example, in “The First Amendment Doesnt protect Trump’s Incitement,” Harvard Law professor Einer Elhauge. says Donald Trump clearly went beyond the First Amendment boundary and incited imminent lawless action.

Unlike the Brandenburg case, “Trump riled up a mob a short walk from the Capitol right before Congress was scheduled to count the certified electoral votes. Both in his tweets calling on supporters to come to Washington and in his speech at the Washington rally, the president falsely stated that allowing Congress to count the certified electoral votes would “steal” the election from him and his followers. In his remarks and tweets in the days before, he said the goal was to “stop the steal,” that their protest would “be wild,” that “you can’t let [the steal] happen,” and that “they’re not taking this White House. We’re going to fight like hell.” …

That implication was confirmed by Trump’s other statements in his speech. He stated that Republicans had been too “nice” and were instead “going to have to fight much harder.” He added that “you’ll never take back our country with weakness. You have to show strength and you have to be strong.” He further exhorted that “if you don’t fight like hell, you’re not going to have a country anymore” and that “they need to take back our country.” Although Trump tried to protect himself by stating that he was sure that the crowd would “peacefully” march to the Capitol, that does not alter the fact that he was inciting the crowd to forcibly stop Congress from counting the certified electoral votes once they got there.

Trump thus clearly incited lawless action (obstructing the operations of Congress is a crime) that was imminent (right after the speech, a short walk away). That he wanted to incite such lawless action is confirmed by reporting that for hours he watched the Capitol attack with pleasure and did not take any steps to stop it by calling out the National Guard or by urging his supporters to stand down….

It is also significant that Trump is the president. In antitrust law, conduct by a monopolist is often treated as illegally anticompetitive even when the same conduct by a non-monopolist would not be treated as such, because the monopolist’s greater power means their conduct is more likely to have anticompetitive effects. A parallel consideration ought to apply under the First Amendment because, compared to incitement by private actors, incitement by a president is much more likely to incite successful lawless action. Presidents have more power to organize large mobs. Further, presidents are in a position to protect their lawless actions by impeding law enforcement, such as failing to call out the National Guard, or by pardoning lawless actions after the fact. The prospect of such pardons may explain why the rioters felt such impunity that they photographed, live-streamed and videotaped their own lawless actions.