.

At a time when journalism is under attack like never before, we need to refresh our understanding of professional ethics.

The gold standard for American journalism is the Society of Professional Journalists Code of Ethics. It is a clear, basic statement of principles and reaches deeply into the conduct of journalism:

— Seek the truth and report it. — Minimize harm. — Act independently. — Be accountable and transparent.

There are more than 400 ethical codes worldwide, according to Adriane White of the Ethical Journalism Network. The five core values in most of these can be summarized as: accuracy; independence; impartiality; humanity; and accountability. A complete list of codes of ethics from publications and independent journalism associations around the world is available at Columbia University’s school of journalism.

Leading American news broadcasters, such as National Public Radio, also have codes of ethics that are more detailed. NPR’s code begins with this statement:

We hold those who serve and influence the public to a high standard when we report about their actions. We must ask no less of ourselves. Journalism is a daily process of painting an ever truer picture of the world. Every step of this process – from reporting to editing to presenting information – may either strengthen or erode the public’s trust in us. We work hard to be worthy of that trust and to protect it.

Accuracy, fairness, completeness, independence, impartiality, transparency, accountability, respect and excellence are core principles for NPR.

These guidelines help us understand what is expected and what standards of excellence we hope to achieve. No journalist is perfect, and as former New York Times editor Bill Kovach and Tom Rosenstiel say in their book Elements of Journalism, the point is not personal objectivity of individual journalists, but rather, a disciplined method to verify facts.

Editorial opinion is often confused with news reporting and interpretation by critics of the press. And while opinion is an important function of the press, opinion writing is not journalism per se. Experienced journalists sometimes become opinion writers because they are experts in public interest issues, but it is expected that they will write from an independent public interest perspective if they continue to call themselves journalists.

The selection of news items, known as agenda setting, is another contentious area. Media critics legitimately point out that each publication or broadcast channel has its own priorities and style, and that these are published or broadcast in a free market of ideas as a matter of editorial choice. But to ask why the New York Times is not more like Fox News is hardly a strike against the Times’ ethics.

Journalism is not now, and never has been, perfect. Work still needs to be done, Kovach and Rosenstiel acknowledge, on developing a system for testing the reliability of journalistic interpretation.

Therefore, an important emphasis in journalism ethics is the willingness to work in an open atmosphere, with a scientific attitude, to show what methods and initial assumptions are in play, and to correct mistakes; in short, to be transparent and accountable, and to live up to the responsibility of the First Amendment.

For that reason, most public officials in US history may have been critical of certain articles or individuals, but they have rarely if ever issued blanket denunciations of the press — until recently.

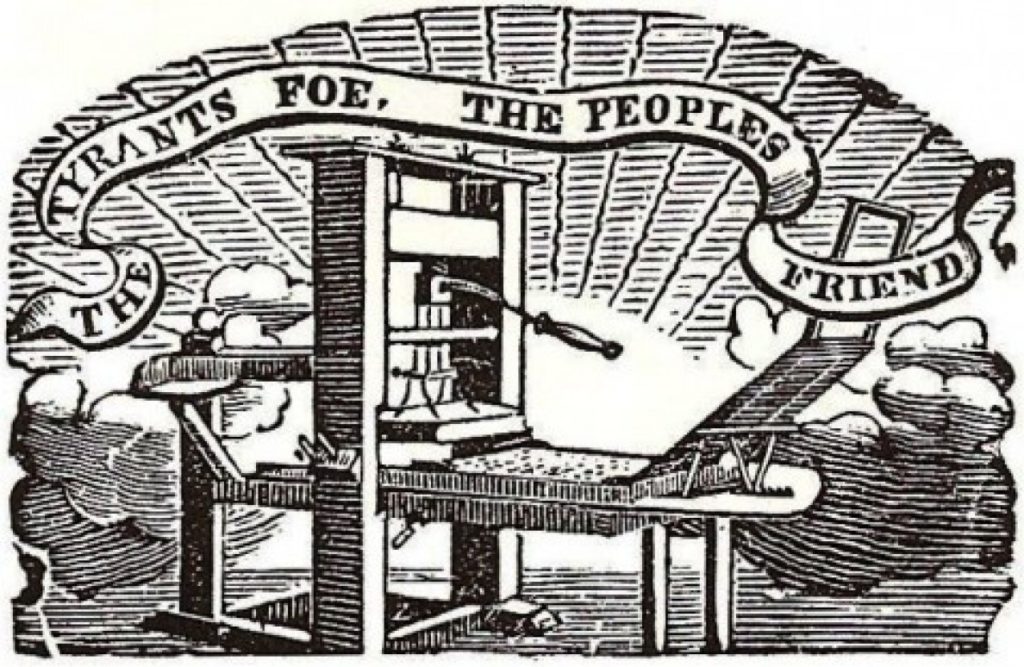

President Donald Trump’s idea that the press is the “enemy of the people” is, we believe, a sad projection and a reversal of an historical truth — that the press is, and usually has been, the tyrant’s foe and the people’s friend, as the ancient woodcut from the American Revolution says.

American journalism does have underlying presumptions which are sometimes called “main street American values,” also known as public interest reporting. Journalists tend to favor public disclosure over secrecy in public affairs; they are supportive of honesty in government over corruption; they are protective of the innocent rather than the exploitative; and they should never lack in sympathy for the poor, (as Joseph Pulitzer once said), as opposed to sycophancy for the rich.

Good journalism is independent and rarely impressed by high position or privilege. It is, at heart, empathetic, humane, down-to-earth and optimistic about the future of the nation and the world.

Minimizing harm: Another important emphasis is to protect the privacy of non-public figures caught up in difficult circumstances. For instance, when Prince Charles or Tom Hanks get COVID-19, it’s newsworthy because they are public figures. But when Nancy Smith down the block gets COVID-19, her privacy deserves protection. Medical professionals are legally bound to protect the identity of people who are victims of a disease, and news professionals are ethically bound to do the same.

The same ethical protections for individual privacy apply to people who are witnesses to a crime, or victims of sexual assault, or juveniles who can be rehabilitated, or private people undergoing difficult divorce or other personal issues.

In some circumstances, private individuals may come forward with their experiences, and that is newsworthy. A speech about the trauma of sexual assault given at a public “Take Back the Night” rally, for example, is newsworthy and serves an important social purpose.

Professional ethics codes in journalism rest on broader foundations, for example, philosophical and religious traditions of ethics; and social responsibility theories of the media.

Ethical considerations in reporting:

For the news media, ethics is not always cut and dried.What is legal is sometimes not what is ethical, and visa versa.

- Don’t publicly identify crime victims: The names of witnesses to a crime, or victims of a crime, will probably be found in public documents, and it may be perfectly legal to disclose them before a trial. But this could be highly unethical, since it exposes the witness to intimidation and the victims to additional suffering. Even when a public trial is held, journalists usually withhold the names & identities of witnesses, juvenile offenders and rape victims — even though they are matters of public record and perfectly legal to publish (As noted in our Section 3.6 on Privacy law and also in cases like Smith v Daily Mail, Cox v Cohn, and Howard v Des Moines Register)

- Respect the principle of innocence until guilt is proven: Police and prosecutors often hope to bias potential jurors with pre-trial releases of damaging information. The problem is that this information may not be accepted by the court. For example, a coerced confession would not be admissible. Yet sometimes police will tell reporters that they “have a confession” in the hope that this will make the prosecutor’s job easier. In short, don’t attempt to try the case in the media; let the courts do their jobs, and wait for pre-trial information to be processed by the courts.

- Avoid deception — In the past, journalists have gone undercover to get a story that might otherwise not be accessible. Famed journalist Nelly Bly went undercover in a New York assylum in 1888, for example. But this is a risky and potentially unethical approach that may lead to trespass charges, for example, in a 1992 ABC News undercover report from a grocery chain, or a voicemail hacking scandal at a Gannett newspaper. There are also pseud0-journalists such as right wing political activist James O’Keefe, who use the idea of undercover journalism for purely political ends, for example, trying to expose wrongdoing by the League of Conservation Voters. According to the Society of Professional Journalists code of ethics, reporters should “Avoid undercover or other surreptitious methods of gathering information unless traditional, open methods will not yield information vital to the public.”

- Be careful with classified military and government information: It may be illegal to publish certain “classified” (secret) information about a government agency, and yet there are cases where journalists go ahead and publish because they are following their ethical duty to serve as watchdogs on government. This was the point in the US v New York Times case over the Pentagon Papers history of Vietnam in 1971. Publication can also lead to problems for the journalist, including jail time.

On the other hand, classified military or intelligence information about the location and strength of troops, about weapons capabilities, about the identities of intelligence agents, about sources and methods of intelligence gathering are among items that are unethical and possibly illegal to publish / broadcast.

These are deep waters and care is needed. Journalists have a “special obligation to serve as watchdogs over public affairs and government,” according to the SPJ code. “Seek to ensure that the public’s business is conducted in the open, and that public records are open to inspection.” But journalists also have an obligation to avoid endangering military and intelligence personnel. - Ads and body image: Some kinds of advertising may be perfectly legal and yet push social boundaries and images into ethically unacceptable directions. The tendency to emphasize extremely thin and unhealthy body shapes for women is often considered unethical. Jean Kilbourne’s work with the “Killing Us Softly” documentary series has helped to bring this issue to light.

- Ads and truthfulness: It may be illegal or contrary to FTC or FCC regulations to fabricate information in advertising, yet social critics like Adbusters and Yes Men do it for reasons they believe are highly ethical, such as poking fun at tobacco advertising or the lack of corporate accountability on environmental issues.