Even though his presidency has come to a close, Donald Trump is still claiming that the press is “the enemy of the people.” The small but fervent crowds at his rallies continue to boo and heckle and roar their hated at the brave souls who stand before the cameras.

Even though his presidency has come to a close, Donald Trump is still claiming that the press is “the enemy of the people.” The small but fervent crowds at his rallies continue to boo and heckle and roar their hated at the brave souls who stand before the cameras.

So, what is it about the press that incites these dark emotions?

Nothing. That is to say, this is not really about the press. Trump’s rhetoric is not aimed at trying to correct the many well-known faults of that institution. The rhetoric is, rather obviously, designed to arouse intense emotions among people whose destructive impulses are easily reached by bombastic cliches.

Immigrants, Mexicans and Muslims have also been subjected to similar smears by this president.

And the truth is that it’s not about Mexicans, or immigrants, or Muslims, and it’s not about journalists. It could be anyone in any group. As authoritarians have learned over the centuries, its easy to pick out a small subset of the population to serve as a convenient target for irrational hatred.

But it’s a dangerous political tactic, and people are speaking out about it. New York Times publisher AG Sulzberger told Trump in a July 2018 meeting that it “is contributing to a rise in threats against journalists and will lead to violence.” Sulzberger “repeatedly stressed that this is particularly true abroad, where the president’s rhetoric is being used by some regimes to justify sweepi

ng crackdowns on journalists.” (For example, an article in The Economist July 25, 2018 notes that “journalists are being crushed in Asia.”)

But the meeting, according to Trump’s July 29, 2018 tweet, was all about him lecturing Sulzberger: “Spent much time talking about the vast amounts of Fake News being put out by the media & how that Fake News has morphed into phrase, ‘Enemy of the People.’ Sad!”

This is the authoritarian passive voice that Orwell warned about. ‘Fake news’ has morphed. Donald Trump didn’t do it. It morphed.

In rallies and speeches, Trump continues to vilify and demean the press, using this kind of language, which is then echoed by the crowd. His antics are often embarrassing to his hosts, like the Veterans of Foreign Wars, which apologized the day after Trump’s July 23 speech.

——

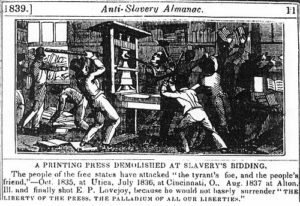

Elijah Lovejoy was killed by a mob in 1837 while defending his printing press in Illinois. Lovejoy was an abolitionist who fought slavery before the Civil War.

Elijah Lovejoy was killed by a mob in 1837 while defending his printing press in Illinois. Lovejoy was an abolitionist who fought slavery before the Civil War.

Trump’s rhetorical tactic is known as “flipping the script,” or sometimes “swift boating.” It is an attack irrationally aimed at the strongest defense of an opponent. It throws people off guard, but it is usually so blatantly ridiculous that it does more harm to the attacker than the victim.

Historically, the press has been well known as the enemy of tyrants. To try to turn the idea on its head, using emotion but not serious argument, is an obvious attempt to deceive credulous people.

The truth is that historically, and today, freedom of speech and of the press is held in reverence by people who love democracy.

A Wikiquote page has hundreds of examples, from John Adams to Alexander Solzhenitsyn.

Historically, and today, journalists have depicted the best of humanity and exposed the worst; they fought for freedom, and against slavery; they fought for justice, and against tyranny; they championed relief for the poor and oppressed; and they led campaigns against public corruption.

Great heroes of the press, such as Benjamin Franklin, Elijah Lovejoy, Joseph Pulitzer, Joe Rosenthal, Ida B. Wells, and many others, made it their mission to lift the vision of the nation and uphold the public interest.

The Virginia Constitution, Section 12, says: That the freedom of the press is one of the great bulwarks of liberty, and can never be restrained but by despotic governments.

Journalists are far from perfect. But until Donald Trump came along, journalists were only called “enemies of the people” in places like Russia, China, Nazi Germany and Saudi Arabia.

———–

History is full of examples of demented leaders who zero in on a likely group of victims without reason. In fact, the lack of reason is what makes it so powerful.

We all know what can happen, that it can lead to places like Auschwitz, Srebrenica, Camp Kigali, and the killing fields of Phnom Penh.

And we also know how it happens. We know it begins with a division of “us” and “them,” and grows into a campaign of vilification and dehumanization. (See the Wikipedia pages on genocide)

We know that to prevent it from growing, we have to:

- Remind people about the universal institutions that transcend divisions.

- Try to prevent symbols from being used as vehicles for hatred

- Condemn the use of hate speech and make it culturally unacceptable.

In Europe and other parts of the world, hate speech is illegal, and use of hateful symbols can lead to arrest.

But in the United States, with a somewhat more open attitude, citizens have an extra responsibility to speak out. In many cases they are. Along with Sulzberger, Republican Senator Orin Hatch has called on Trump to stop vilifying the media. Many others have done so as well.

To paraphrase Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis famous dissent in the 1927 Whitney v. California opinion, the remedy for bad speech is more speech, and better speech.

What we need is the kind of speech that reminds us of our heritage, awakens our reason and elevates our vision.