Before libel lawsuits became routine in the early 1800s, conflicts over reputation often resulted in duels. This is a depiction of the tragic Burr-Hamilton duel of 1804.

People have always tried to protect their reputations. An outright duel between two pistol or sword wielding opponents was one way. Libel suits were another.

In the late 18th century, lawsuits for libel were increasingly seen as a way to avoid duels, which could be deadly and often destroyed both plaintiff and defendant. The most tragic example was the death of former Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton in a duel with then vice-president Aaron Burr on July 12, 1804. Ironically, it was Hamilton who made one of the most important initial contributions to an American framework for libel law, arguing a case only a few months beforehand.

Truth as a defense

In the old British legal system, seditious libel involved any words, true or not, that damaged the reputation of the government. The exception, as we’ve seen, was the jury’s verdict of innocence in the John Peter Zenger trial of 1735, in which the jury said that truth was a defense against seditious libel. The Zenger decision had far-reaching effects, but in the newly free American states, no one was sure how complete a defense it was.

Libel laws and precedents varied from state to state in the late 18th and early 19th century, but the case that helped harmonize libel was was the 1803 People of New York versus Croswell. In this case, a Federalist editor was charged with several counts of libel and sedition for (among other things) attacking then-president Thomas Jefferson, alleging that he (Jefferson) financed a smear campaign against George Washington.

Croswell was found guilty and he appealed to the state supreme court of New York. In a famous argument for Croswell to the judges of the NY supreme court, pro-Federalist lawyer and former Treasury secretary Alexander Hamilton argued that truthful statements should not be considered defamatory.

The right of giving the truth in evidence, in cases of libels, is all-important to the liberties of the people. Truth is an ingredient in the eternal order of things, in judging of the quality of acts. — Alexander Hamilton, Feb. 13, 1804.

The judges could not reach a decision, and Croswell was never sentenced. The next year, the state legislature adopted Hamilton’s argument as law, breaking with the old standard and affirming that truthfulness alone is a defense in libel. The New York standard became the norm for most states and a cornerstone of American law.

Not all states adopted the Croswell standard, and before the Civil War, the Bill of Rights (including the First Amendment) did not necessarily apply to state cases. * (*A property case, Barron v. Baltimore 32 U.S. 243, 1833, was the Supreme Court precedent for state supremacy in questions of Constitutional rights.)

Federal supremacy was officially established by the 14th amendment, passed in 1866 in the wake of the Civil War. Even then, state laws were still considered primary until they were “incorporated” — one by one — under the US Bill of Rights over a period of decades. The First Amendment was “incorporated” in a series of prior restraint cases: Gitlow v. New York (1925); Whitney v California (1928); and Near v. Minnesota (1930).

Burden of Proof

In 19th and early 20th centuries, libel plaintiffs had a much easier time winning a libel case than they do today. Here’s why:

- The burden of proof was on the publisher. (Note: In Canada and some other nations, the burden is still on the publisher. Britain changed its legal preference for the plaintiff in 2010.)

- Strict Liability – The case was judged under a “strict liability” standard — defamation under any circumstances would result in judgement against the media.

- Harm was assumed to a plaintiff’s reputation; there was no need to prove general damages.

These rules added up to a chilling effect on freedom of speech, and so, an offsetting system of privileges was developed in common law. Speeches by legislators, reports from official records, and fair comment about public officials or candidates for office became more or less tolerated under various state laws. Comments about literary or artistic works were also tolerated under the “fair comment” concept.

Despite this common law background, state libel laws tended to lean towards the interests of the plaintiff and not the news media or others exercising free speech rights. In fact, libel suits were one of the most effective weapons against advocates of change. “White government officials wielded libel law to protect white supremacy and waste the time and funds of those individuals and organizations that worked to dismantle segregation and end police brutality,” said Aimee Edmondson in the book In Sullivan‘s Shadow: The Use and Abuse of Libel Law During the Long Civil Rights Struggle,

For the most part, this changed with the 1964 case, New York Times v Sullivan, which we will discuss in the next section. But first, here are some of the kinds of cases that characterized libel late in the 1800s and early 1900s.

Famous Libel cases

Cherry v Des Moines Leader, 1901

The Celebrated Cherry Sisters were probably the worst act on the vaudeville circuit at the turn of the 20th century. When they sued their critics, in Cherry v Des Moines Leader , 1901, the sisters went down in libel history.

The homespun combination of sentimental songs and odd prairie dancing was so abysmally bad that it attracted audiences who enjoyed booing, hooting and throwing rotten vegetables. In fact, they often performed behind a net so that the rotten vegetables would not hit them.

They felt compelled to sue for libel when Des Moines Leader newspaper editor Billy Hamilton wrote this scathing review:

Effie is an old jade of 50 summers, Jessie a frisky filly of 40, and Addie, the flower of the family, a capering monstrosity of 35. Their long, skinny arms, equipped with talons at the extremities, swung mechanically, and soon were waved frantically at the suffering audience. The mouths of their rancid features opened like caverns and sounds like the wailings of damned souls issued therefrom. They pranced around the stage with a motion that suggested a cross between the danse du ventre [belly dancing] and a fox trot –strange creatures with painted faces and hideous mien. Effie is spavined, Addie is stringhalt, and Jessie, the only one who showed her stockings, has legs without calves, as classic in their outlines as the curves of a broom handle.

Their lawsuit failed at the trial level, and the Cherry Sisters asked the Iowa Supreme Court for a finding of actual malice against Hamilton and the Des Moines Leader, which had republished his article. But the Court said:

One who goes upon the stage to exhibit himself to the public, or who gives any kind of a performance to which the public is invited, may be freely criticized … The comments, however, must be based on truth, or on what in good faith and upon probable cause is believed to be true, and the matter must be pertinent to the conduct that is made the subject of criticism. Freedom of discussion is guarantied by our fundamental law and a long line of judicial decisions. [T]he editor of a newspaper has the right, if not the duty, of publishing, for the information of the public, fair and reasonable comments, however severe in terms, upon anything which is made by its owner a subject of public exhibition, as upon any other matter of public interest; of privileged communications, for which no action will lie without proof of actual malice. Surely, if one makes himself ridiculous in his public performances, he may be ridiculed by those whose duty or right it is to inform the public regarding the character of the performance. Mere exaggeration, or even gross exaggeration, does not of itself make the comment unfair. It has been held no libel for one newspaper to say of another, “The most vulgar, ignorant, and scurrilous journal ever published in Great Britain.” A public performance may be discussed with the fullest freedom, and may be subject to hostile criticism and hostile animadversions, provided the writer does not do it as a means of promulgating slanderous and malicious accusations.

More about the Cherry Sisters:

- Hilarious WFMU Radio story on the Cherry Sisters.

- Wikipedia article on the Cherry Sisters

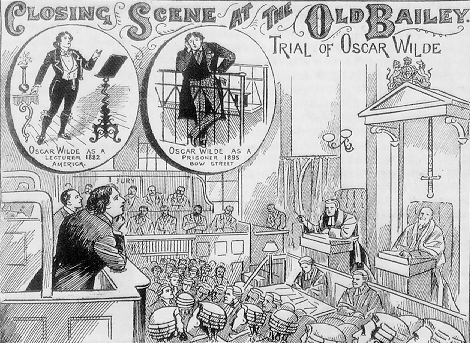

Oscar Wilde v the Marquis of Queensbury, 1895 (Britain)

Oscar Wilde was a famous playwright and well-known wit about town in London in the 1880s and 90s. He was also reckless. In 1895, he brought a libel suit against the Marquis of Queensbury, the famous boxing rules champion, for insulting him in public, calling Wilde “a sodomite” — a derogatory term for homosexual. If he lost, the marquis would have had to spend two years in jail.

However, during the trial, the marquis’ attorneys brought some of Wilde’s lovers to the witness stand, including the son of the marquis. Convincing evidence of his homosexuality inevitably came forward.

Not only did the marquis win the libel suit, but Wilde was arrested and tried on criminal charges of sodomy. He ended up spending two years in British jail and died, his career cut short, in 1900.

For more on the Wilde trial: Prof. Douglas O. Linder‘s Famous Trials

Annie Oakley v the Hearst papers 1903 – 1910 (US)

Was Annie a cocaine addict? Two Chicago newspapers belonging to William Randolph Hearst published an entirely false article on August 11, 1903, headlined “Famous Woman Crack Shot … Steals to Secure Cocaine.”

Was Annie a cocaine addict? Two Chicago newspapers belonging to William Randolph Hearst published an entirely false article on August 11, 1903, headlined “Famous Woman Crack Shot … Steals to Secure Cocaine.”

The story said Oakley had been sentenced to 45 days in a Chicago prison, for “stealing the trousers of a negro in order to get money with which to buy cocaine.” Oakley’s beauty had vanished, the reporter said: “Although she is but twenty-eight years old, she looks almost forty.”

The truth behind the story was that someone arrested on cocaine charges signed her name “Annie Oakley” and the newspaper, without applying any ethical standard, took this at face value. In fact, Oakley was 42, she was in New Jersey at the time of the story, and she was not a cocaine user. She embarked on a series of 55 libel suits against newspapers that printed the story, winning all of them but losing money in the process.

Hearst’s smear campaigns were part of the way he did business. Any embarrassing rumor or half-truth would be used to ruthlessly ruin famous people and in the process boost Hearst and his publishing empire.

Animal rights advocates sued by scientists in Bayliss v Coleridge, 1903 (Britain)

Stephen Coleridge, anti-vivisectionist, libel defendant, (1910)

People who love animals were outraged in the early 1900s when they learned that medical students were cutting open living dogs and performing experiments (“vivisection”) as a routine part of their education. Scientists and doctors strongly insisted that the experiments were needed.

The issue first came to a head when Stephen Coleridge, secretary of the National Anti-Vivisection Society, gave an angry speech on May 1, 1903, describing one incident in which a brown dog was repeated used by University College professor William Bayliss for experiments. Coleridge said the experiments were taking place without proper anaesthesia, in violation of the Cruelty to Animals Act. “If this is not torture, let Mr. Bayliss and his friends … tell us in Heaven’s name what torture is.” Bayliss sued for libel and the case was heard in November 1903.

The trial hinged on Coleridge’s acceptance of a single eyewitness account without checking for other witnesses or learning more from Bayliss himself. Since the legal burden was on the defendant (Coleridge) to prove the truth of his allegations, and since there was no absolute proof that the brown dog was being tortured or that there was a violation of the law, the court found Coleridge guilty of libel. Bayliss was awarded £2,000 with £3,000 costs. The ever-conservative Times of London said it was satisfied with the verdict, but most other newspapers and all the animal rights groups called the decision a miscarriage of justice.

American writer Mark Twain was especially moved by the trial and wrote a short story called A Dog’s Tale from the point of view of a dog whose puppy is subjected to experiments. As the controversy over vivisection continued, a statue to the Brown Dog was erected with the motto: “Men and Women of England, how long shall these Things be?” Medical students in London were outraged and staged a series of violent riots intended to intimidate anti-vivisectionists. Tired of the controversy, the Brown Dog statue was removed in 1910 by a suburban London council.

—————————————————————————

How far can an art critic go? Whistler v Ruskin, 1878 (Britain)

Oxford professor John Ruskin, a famed romantic poet and literary critic, criticized a painting by the American artist James McNeil Whistler, saying:

I never expected to hear a coxcomb ask two hundred guineas for flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face.

Whistler sued Ruskin in British court for 1,000 pounds. The jury found Ruskin guilty but awarded Whistler only one farthing (one tenth of one cent). The jury, obviously, believed the law supported Whistler but did not care for the way he attacked Ruskin. Most observers believed it was a defeat for both men who had allowed their disagreement about a work of art to become a costly public libel trial.

Why we regulate advertising today: Collier v Postum, 1907 (US)

This 1910 ad shows the style of Postum’s advertising.

Charles W. Post, whose Post cereal company made Postum, often ran ads claimed miraculous curative powers for his Grape Nuts cereal. But when he claimed it would “obviate the necessity of an operation for appendicitis,” Peter F. Collier, publisher of Collier’s magazine, said Post was engaged in “potentially deadly lying.”

In response, Charles Post launched a campaign of intimidation, claiming that Colliers tried to extort money in return for its silence.

At that point, in 1907, Collier sued Post for libel and was awarded $50,000 damages.

On appeal, in 1912, the judgement was reversed on error and remanded for a new trial, but that apparently never occurred. The story demonstrates the abysmal level of regulation over commercial medical claims in the early 1900s. It is part of the reason why advertising in general became regulated and was not considered to have First Amendment protection until the 1960s.

US v Press Publishing Co (NY World), 219 U.S. 1, 1911

When Joseph Pulitzer and other publishers alleged that there had been a $40 million bribe in connection with the purchase of land for the Panama Canal, US president Theodore Roosevelt was outraged. Pulitzer’s New York World newspaper alleged that Roosevelt and others had conspired to bribe French officials to relinquish claims to the Panama Canal.

The suit originated with grand jury indictments in Washington DC on Feb. 17, 1909, on charges of criminal libel, and also in New York March 4, 1909, the day Roosevelt left office.

The New York indictments were unusual in alleging that the supposed libel was a violation of an 1825 federal law prohibiting malicious injury to harbor defenses. Since the New York World newspaper had been circulated at West Point military academy, and it was (theoretically) a harbor defense, the attack on the president was a malicious act against a military base.

Arguments were heard before the Supreme Court on October 24, 1910, and not surprisingly, on January 3, 1911, the court quashed (threw out) the criminal libel indictment. This was not the resounding victory for freedom of the press that Pulitzer had hoped for, but on the other hand, the court repudiated this use of an unusual law for political persecution by former authorities against their political detractors in the press.

This kind of seditious libel suit was not seen again in the United States until the presidency of Donald Trump. See “Another Laughable Libel Suit”

Henry Ford v The Chicago Tribune, 1916 – 1919

In 1916, Ford company warned its employees that they would lose their jobs if they volunteered for the National Guard in order to fight what was then a small-scale border war with Mexico. This annoyed Robert McCormick, the irascible editor of the Chicago Tribune, who wrote ran an editorial entitled “Flivver Patriotism:”

In 1916, Ford company warned its employees that they would lose their jobs if they volunteered for the National Guard in order to fight what was then a small-scale border war with Mexico. This annoyed Robert McCormick, the irascible editor of the Chicago Tribune, who wrote ran an editorial entitled “Flivver Patriotism:”

If Henry Ford allows this rule to stand, he will reveal himself not merely as an ignorant idealist but as an anarchist enemy of the nation which protects his wealth. The proper place for such a deluded human being is a region where no government exists except as he furnishes … Any place in Mexico should be a good location for Ford factories.

Civil rights libel suit: Aaron Sapiro v Henry Ford, 1927

Aaron Sapiro, a Jewish lawyer, was described in Ford’s Dearborn Independent as an “international financier who will enslave American farmers and eventually replace the American state with this international (Jewish) conspiracy.”

Sapiro was actually working to organize farmers cooperatives in Canada and California. He sued Ford for libel in 1925 and Ford had to settle with him and agree to shut down the virulently anti-semitic Independent.

This lawsuit was one of the first that used the Civil War-era conspiracy statute, the Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871, to allow private lawsuits for civil rights violations. A similar civil rights lawsuit – Sines v Kessler – against the organizers of the 2017 Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Va., ended with a November 2021 verdict of $25 million against the anti-semitic defendants.

G.W. Price v. The California Eagle and Charlotta Bass, 1925

G.W. Price v. The California Eagle and Charlotta Bass, 1925

Libel suits filed to fight the civil rights movement

Before NY Times v Sullivan, libel suits were often filed to suppress criticism of the white establishment in the American South. These examples are taken from Aimee Edmondson’s 2019 book “In Sullivan’s Shadow.”

-

John Henry McCray

In October 1949, John Henry McCray, editor of the South Carolina Lighthouse, reported a death row interview with George Thomas, a man who had been convicted of raping a white woman and who was subsequently executed. Thomas insisted that his relationship was consensual. For reporting this, McCray was charged with criminal libel and forced to serve two months on a chain gang in 1954, even though white newspapers reported Thomas’ statement without any penalty. McCray shut down the newspaper soon afterwards.

- In 1955, a Florida NAACP official suggested that a state legislator helped communism by proposing to abolish public schools rather than integrate them. Florida courts ordered the NAACP official to pay $15,000 in fines.

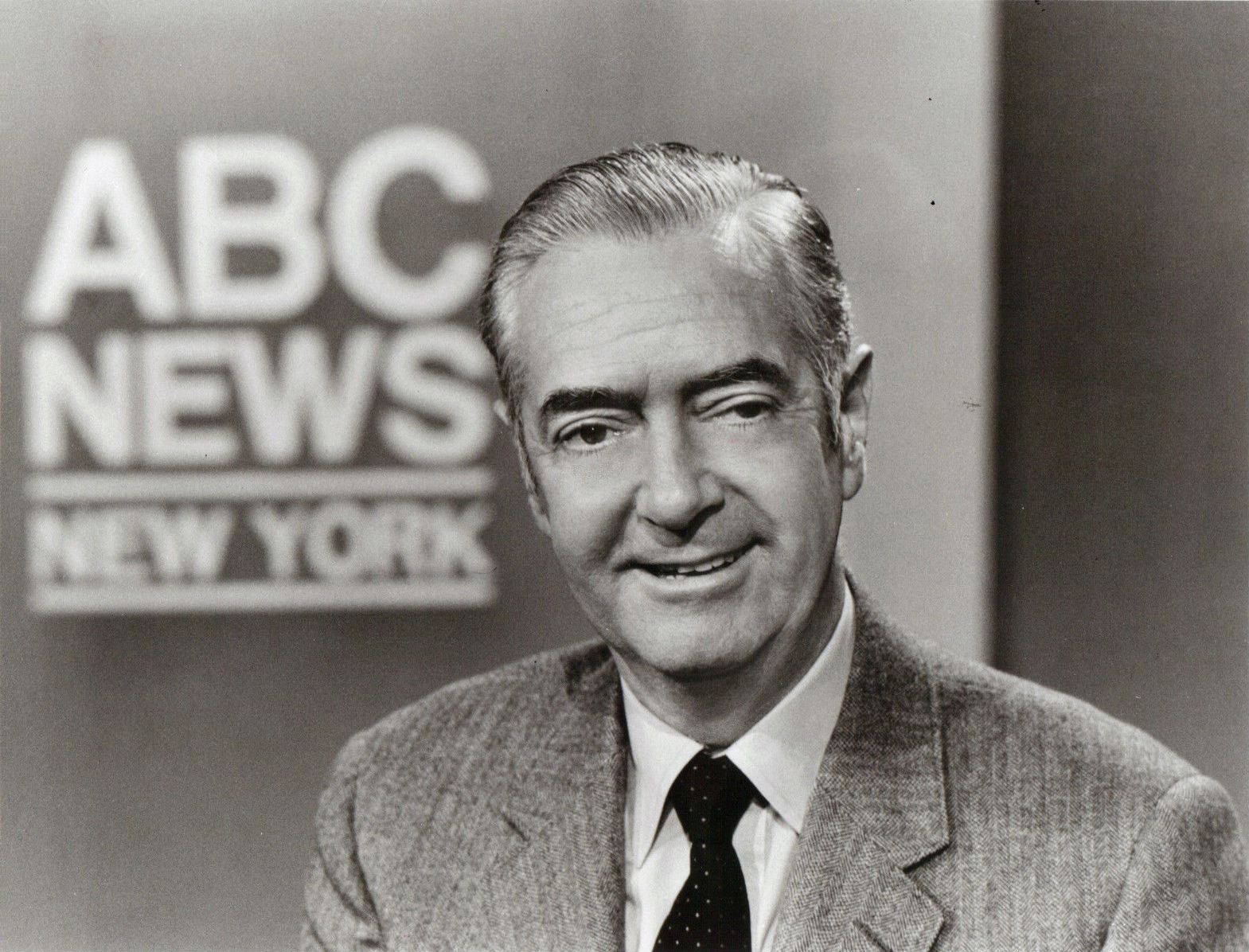

Howard K. Smith

- In 1961, CBS journalist Howard K. Smith aired a program “Who Speaks for Birmingham” that asked how civil rights demonstrators were being treated. The answer – not very well, considering that they were being attacked by police dogs. Smith clearly sympathized with the demonstrators, and city officials complained in a libel suit that the report lacked balance. Rather than defending the suit, and Smith, CBS settled out of court and issued an on-air apology. Soon afterwards, Smith quit CBS and moved to ABC.

These and other anti-civil rights cases are found in Aimee Edmondson’s 2019 book, In Sullivan’s Shadow, and are also discussed in the AEJMC History Division Podcast: “For many years, the far right has sown public distrust in the media as a political strategy, weaponizing libel law in an effort to stifle free speech and silence African American dissent. In Sullivan’s Shadow demonstrates that this strategy was pursued throughout the civil rights era and beyond, as southern officials continued to bring lawsuits in their attempts to intimidate journalists who published accounts of police brutality against protestors. Taking the Supreme Court’s famous 1964 case New York Times v. Sullivan as her starting point, Aimee Edmondson illuminates a series of fascinating and often astounding cases that preceded and followed this historic ruling.”

————————————————————————–

Quentin Reynolds v Westbrook Pegler and Hearst Corp. 1955

This was a classic newspaper feud between a liberal columnist (Quentin Reynolds) and a conservative one (Westbrook Pegler).

Pegler wrote about Reynolds in 1954, saying that Reynolds and his “girl friend of the moment were nuding along the public road,” that the neighbors might not understand, and if “they saw Reynolds and his wench strolling along together, absolutely raw, they would call the State police;” that “as Reynolds was riding to (Reynolds’ friend) Heywood Bruin’s grave with her, he proposed marriage” to the widow; that Reynolds “became one of the great individual profiteers of the war” and “cleaned up $2000 of the ill-gotten loot of the Garson brothers who, with Congressman Andy May, later were convicted of fraud in war contracts”; that he was a “four-flusher,” with “an artificial reputation as a brave war correspondent in the London blitz,” one of the “`let’s you and him fight’ school of heroes” and that Clare Boothe had “peeled him of his mangy hide and nailed it to the barn door with the yellow streak glaring for the world to see.”

The court found for Reynolds and fined Hearst $175,000 in damages — the largest fine ever at the time. The trial became a Broadway play, A Case of Libel, and several made-for-TV movies.

Other libel suits

- History and theory of the law of defamation Columbia Law Journal, 1903.

- Criminal libel trial of “Confidential” magazine, California, 1957

- The Massacre and the Ministers (Tolstoy v. Addington, 1996 ? )

- The McLibel Trial, 1997

- Tom Cruz versus the Express on Sunday magazine 1998