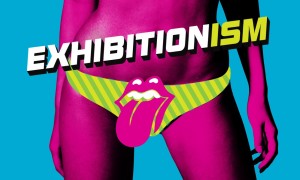

Who would be offended? Not Rolling Stones fans. But in 2015, the people who run the London subway and bus services were not happy with it.

Just how offensive is this ad for a Rolling Stones exhibit?

Too offensive for the London tubes, according to the transport authority of London, in July of 2015. The transport authority has the ability to decline advertising under some circumstances, even though it is owned publicly (by the government). This is true of “public” (government-owned) media in both the US and the UK, and particularly with airport, bus or subway ads.

These public media regulated in ways that are different from broadcast media, which are regulated by the FCC in the US and by the Ofcom in the UK. They are also quite different from print media, such as newspapers, magazines and private billboards.

For example, there would probably be no decency issue problem for the Rolling Stones to advertise their “Exhibitionism” exhibit in newspapers, magazines or privately – owned billboards. There might not be a problem on television. But public media are free to define rules that are more strict so long as they are consistent and content neutral.

Public media guidelines

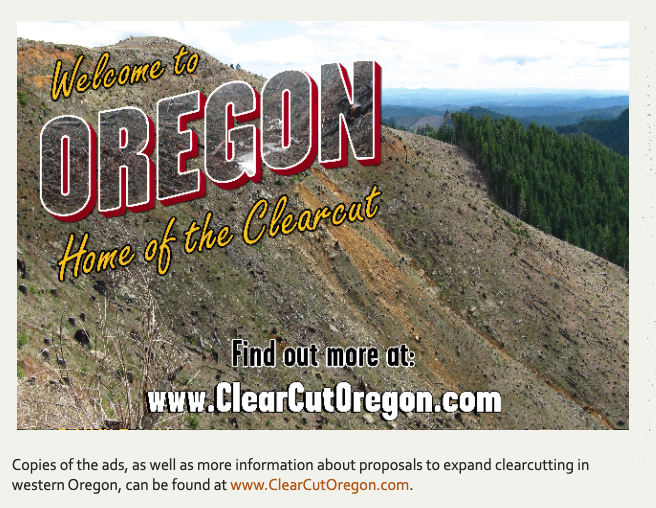

In the US, consistency in advertising policy is a state by state issue. A similar case opened over political advertising in Oregon in the fall of 2013 when an airport in Portland, Oregon, turned down an environmental coalition’s ad opposing clearcutting in forestry. But state laws in Oregon meant that the airport’s decision could be over-ruled even if, under federal case law, such decisions could stand in other states.

The main controlling public media case in the US is the 1974 ** Lehman v. Shaker Heights 418 U.S. 298. Here a candidate for office wanted to advertise on a city-run bus line. The Supreme Court said that the city was free to limit its advertising to commercial products only so long as it did so consistently and from a content-neutral point of view.

States are free to be less restrictive — but not more restrictive — when it comes to public media advertising, according to another supreme court case, Pruneyard Shopping Center v. Robbins, 1980. Because California’s constitution has a positive right of free speech, the case was decided in favor of permitting a petition drive that a shopping center did not want to allow. Oregon has a similar constitutional provision, which is why the clearcutting ads were permitted in the Portland airport. However, most US states do not, and the European Court of Human Rights held in Appleby v UK, 2003, that there is no right to advertise controversial subjects in public media in Europe.

Applying Lehman v Shaker Heights In September of 2013, a coalition of environmental groups in Oregon launched an advertising campaign to stop clear-cutting of forest lands. They asked to buy billboards at the Portland airport, and the airport authority refused, saying that they were political ads.The airport argued that political statements should not be permitted on government property (the airport). Oregon state courts disagreed, saying that the US First Amendment was the most important factor, and the airport was ordered to allow the advertising. Although not a major case, Oregon Natural Resources Council Fund v. Port of Portland exemplifies some of the value conflicts that can surround advertising. Applying Lehman v Shaker Heights In September of 2013, a coalition of environmental groups in Oregon launched an advertising campaign to stop clear-cutting of forest lands. They asked to buy billboards at the Portland airport, and the airport authority refused, saying that they were political ads.The airport argued that political statements should not be permitted on government property (the airport). Oregon state courts disagreed, saying that the US First Amendment was the most important factor, and the airport was ordered to allow the advertising. Although not a major case, Oregon Natural Resources Council Fund v. Port of Portland exemplifies some of the value conflicts that can surround advertising.

A similar case involving California’s Karuk Tribe advertising on busses was also decided in favor of political issue oriented advertising a few years earlier. And yet, many airports routinely reject politically oriented and religious advertising. Washington DC Reagan National even rejected ads encouraging people to keep their guns locked up and away from children. Yet a more controversial ad on Philadelphia busses would have to be allowed, the courts said. These cases illustrate differences in state approaches to public forum analysis and constitutional speech issues. |

Is there a right to place advertising in media?

1. Maybe in public media with Lehman case

2. Yes in broadcast media with Equal Time Rule (Section 313) when a political campaign for federal office is under way.

3. No in print media — Miami Herald v. Tornillo 1974 — Here the Supreme Court said that a Florida law imposing a “right of reply” on the print media was not constitutional. A candidate for public office insisted that the Herald print his advertisement responding to a Herald editorial, and the Herald refused. The court said that the print media had a right to control its contents without government interference. While the press should be responsible, Chief Justice Warren Burger said, “like many other virtues it cannot be legislated.”

MORE