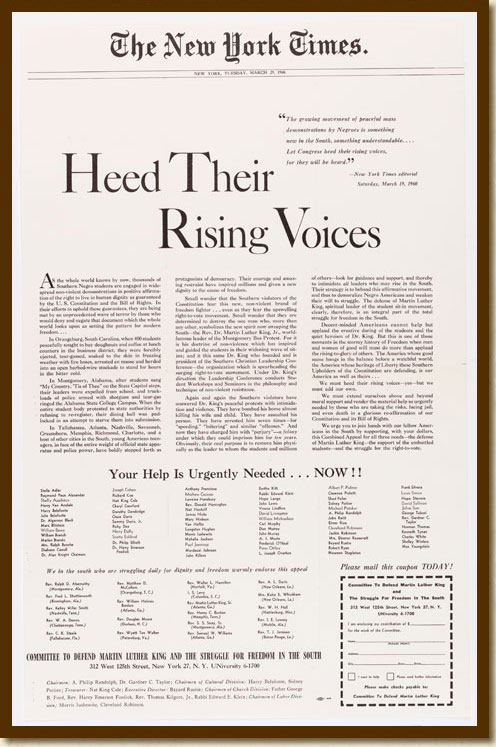

This ad was the subject of the New York Times v Sullivan lawsuit. Click through for full text. (National Archives).

In the wake of the patent advertising and unsafe food scandals of the early 20th century, commercial speech did not have First Amendment protection. This was reaffirmed in the Valentine case in 1942 (below).

But by the 1970s, when the anomalies in the original hierarchy of speech doctrine became obvious, the courts started with a two-tier view of speech, as either protected or unprotected. But there were problems.

For example, an ad asking for help in the Civil Rights movement (New York Times v Sullivan, below) is clearly political. But what about an offer for abortion services? Is it political or commercial? Or how about generic medicine for senior citizens — wasn’t there a political dimension to the way pharmaceutical companies held back generic advertising? Eventually, the lack of distinction between commercial and political speech led the court to provide First Amendment protection for almost any truthful commercial speech.

Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, 1942 — In this well known “fighting words” case, Walter Chaplinsky, a member of the Jehova’s Witnesses religious organization, called a police officer a “fascist” as he was being arrested for disturbing the peace. In ruling that the police officer did not violate Chaplinsky’s rights, the court issued a “two-tier theory” of the First Amendment, in which there were “certain well-defined and limited classes of speech, the prevention and punishment of which have never been thought to raise any constitutional problem.” Although Chaplinsky was a mostly prior restraint case, the idea of a “two-tiered” approach to the First Amendment guided advertising doctrine for several decades.

** Valentine v. Chrestensen, 316 U.S. 52, 1942 — The Supreme Court said that the First Amendment does not apply to commercial advertising. F.J Chrestensen had a surplus Navy submarine on display and was advertising it with handbills passed out on New York streets. However , a city ordinance allowed only political handbills on the street. The court said that the Constitution “imposes no restraint on government as respects commercial advertising.”

** New York Times v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254, 1964 — Although this case involved advertising, the Supreme Court took pains to distinguish it from the Valentine case because it involved “idea” or political advertising, which had full First Amendment protection. (See section on libel law). The Court took pains to distinguish this case from Chrestensen,: “The publication here was not a “commercial” advertisement in the sense in which the word was used in Chrestensen. It communicated information, expressed opinion, recited grievances, protested claimed abuses, and sought financial support on behalf of a movement whose existence and objectives are matters of the highest public interest and concern.”

Pittsburgh Press v Pittsburgh Commission on Human Relations, 413 U.S. 376, 1973 — A city ordinance banning sex descrimination did apply to newspaper classified ads for employment. Before this, newspaper classified help wanted ads were always categorized under “Help Wanted: Male” and “Help Wanted: Female.” After this case, newspaper advertising changed nationwide and no gender distinctions were permitted.

** Bigelow v Virginia 421 US 809 1975 — An advertisement in a University of Virginia paper, the Virginia Weekly, for abortion services in New York City was both political and commerical. The court upheld Bigelow’s right to advertise and inform people of abortion services in other states. (Note this case came up just after Roe v. Wade).

Va. Board of Pharmacy v. Virginia Citizens Consumer Council 1976 — Before this decision, pharmacies were not free to advertise the price of drugs and the availability of generic drugs. The decision allowing advertising is another example where the Court could no longer separate commercial and political speech.

Bates v. Arizona State Bar 1977 — Supreme Court said state regulation of professional advertising for lawyers is not constitutional. Bates is another commercial speech case with political underpinnings. In this case, lawyers for a legal aid service to low income Hispanics challenged state laws forbidding advertising by lawyers and won.

** Central Hudson Gas & Electric Corp. v. Public Service Commission (PSC) of New York, 447 U.S. 557 1980 — This case is important as a major test of the validity of government restrictions on commercial and corporate speech. The PSC had issued rules forbidding advertising that might encourage consumption of electricity. (It was the “energy crisis,” after all.) Central Hudson challenged the rules. The Supreme Court used the case to issue a FOUR PART TEST for determining whether government restrictions are valid:

1. Does the ad involve a lawful activity?

2. Is there a substantial government interest?

3. Does the regulation advance this interest?

4. Is the regulation the least restrictive means to serve the interest?

Bolger v. Youngs Drug Products Corp 1983 — This case involved straightforward advertising of condoms through the mail. The US Postal Service said the company could not mail such ads. The Central Hudson test was applied, USPS claiming substantial government interest in preventing interference with parents attempts to discuss birth control.. However, the court said the Postal Service regulation was overly broad. “The level of discourse reaching a mailbox cannot be limited to that which would be suitable for a sandbox.” This argument is often cited in obscenity cases.